Pandemic couldn’t knock down this decades-old dominoes game

These septuagenarian pals have been in a dominoes game that has continued for more than 50 years, since their days at Howard University in the 1960s.

Bam! Bam! Crack-crack! Slam!

This used to be the sound of the Davis basement in Silver Spring, Md., on Sundays.

“Like gunshots,” the exasperated wife said.

This is also the sound that the men of the dominoes miss most.

“The slamming doesn’t work on Zoom,” said Howard Davis, the dean of the domino men, who make the rapid-fire crack and slam of their pieces on the table an essential part of their raucous game.

But they did manage to preserve the laughs, the cuts, the trash talk, the “man gossip” of their dominoes game during the coronavirus pandemic — an ongoing game that has lasted at least half a century.

That’s right — Davis and his septuagenarian pals have been in a dominoes game that has continued for more than 50 years, since their days at Howard University in the 1960s.

“We brought our skills from Jamaica. Dominoes is ubiquitous in the Caribbean; my father played, my grandfather played,” Davis, 76, explained to me after he gave me the delightful honor of sitting in on one of the Sunday night games. “Even the generations coming up now, after us, are playing.”

Most of the domino men left Jamaica for college and bigger opportunities. A couple even go as far back as elementary school — Half Way Tree Primary in Kingston — before reuniting in D.C. A couple of them went to law school in the United Kingdom. But somehow, over the years, they all found themselves back at the domino table.

“Bones” is what some folks in the African American community call it, for the animal material used way, way, waaaay back.

“That was before my time,” Davis made sure I understood.

This group plays a Jamaican partner game with heavy, white thermoplastic dominoes — double-sixes — and back in the day it wasn’t unusual for a game to last 24 hours.

“When we used to play in person, we would stay up all night, coming out of the basement in the sunlight,” Davis said.

His wife, American University law professor Angela Davis, told me the slamming of the tiles was rough, sure.

“But she was glad to know I was home,” Howard Davis, a retired civil engineer, told me.

“The guys would be drinking, they didn’t want to go home, didn’t want to come home at 3 a.m. or drive home after drinking, so they’d just stay,” he said. “There would be food ... escovitch, curried goat, jerk chicken.”

They’d talk politics and track — “Jamaicans love talking about track,” Davis said. “Or even American football or the latest wife.”

“We stayed away from religion,” he added.

And, over time, one of the wives even joined them.

If one moved away, they’d road-trip to see him and keep the all-night games going, well into their 70s, piling into rental cars to go between Atlanta and Florida and even flying to Jamaica or England.

“Marriages, children, grandchildren,” Davis said, the game survived all the life milestones. “The dominoes, that was sort of the glue that held all of us together.”

Then the pandemic hit.

“We tried talking on Zoom. All of us figured out Zoom so we could talk,” Davis said. “But it wasn’t the same. It was hurtful. It was painful not to play.”

They were itching to slam down those smooth little bricks and tear each other’s logic apart in the ongoing, post-move analysis. By December, they’d had enough of the chitchat and tried to start playing online.

“We tried a few of the apps,” he said. But they were unwieldy, and it wasn’t easy to include all of the players in their partner game.

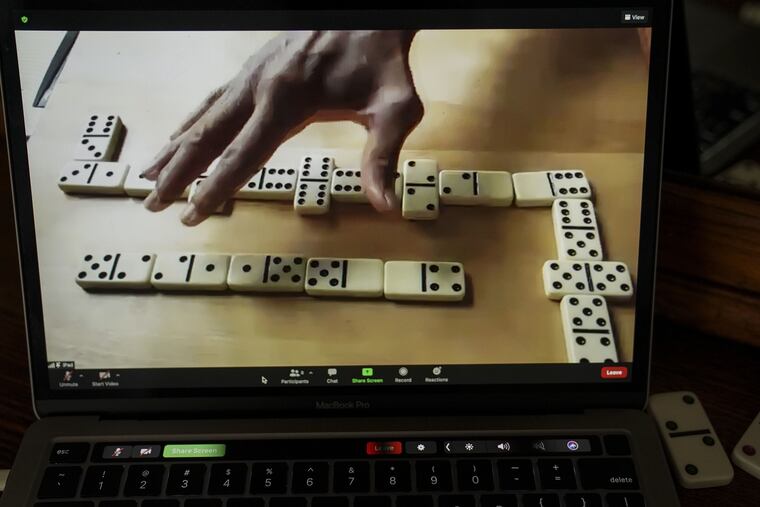

So the engineers got to work engineering it. They decided to work on the honor system, with a single dealer. He has an iPad focused on the dominoes on a table, and a webcam on his face. He deals each hand and shows the dominoes to each player while the rest of them turn around. It’s elaborate and awesome and I sat in — via Zoom — on a recent Sunday to see how they do it.

Davis sits on a balance ball. Even online, the game goes for hours.

“On Zoom, our record is going on 13 hours,” he said. “That’s hard on the back.”

He was the dealer that night, bounce, bounce, bouncing on his balance ball for hours. The players Zoomed in from England, Atlanta, Florida and New York that evening.

Clack, clack, clack, he’d mix up the dominoes and pull a hand. And sure enough, the screen grid showed the backs of eight seniors’ heads, as they turned around for the draw. Honor.

“Okay, Ferdie. This is you,” he’d say. And Ferdie, whose screen was a little askew that night and mostly showed the top of his head and a puff of gray hair, took a photo of his hand of dominoes with his phone.

“Got it,” Ferdie said.

This is the man with a photographic memory, the best of the players, Davis later admitted, after they all crowed and claimed that title when I asked.

The game is fast. Each of the men call out their move in the patois of the game:

“Double deuce.”

“Trey deuce.”

“Alvin, Alvin, your turn!”

“Five ace.” Bounce, bounce, bounce.

“Now that track season is over, what are we watching?”

“Four ace.”

“Trey five.”

“I’m watching every football game I can,” Dennis said.

“Winston! Go!”

“Double deuce.”

There’s a squabble over a move.

“That was two games ago,” Dennis protested.

“Trey ace.”

“I’m watching the games to see who kneels.”

“Deuce trey.”

They’d been going since 2 p.m. that day. I joined in for nearly two hours, then had to call it a night by 10. They stayed up for several more hours after I left.

It’s the thing they look forward to all week, the excuse to stay in touch, the social interaction, camaraderie, the mental health medicine that makes the isolation of the pandemic survivable.

“We’re all in our twilight years; we have more yesterdays than tomorrows,” Davis said. “And we needed this.”