In Philadelphia, residents and artists work together to tackle extreme urban heat through art and education

Heat Response PHL is a two-year initiative that brings local artists and neighborhood residents together to create solutions to highlight climate change through art, engagement, and education.

At the Iglesias Garden in West Kensington, three children sat at a large table with pencils and crayons in hand along with artists Keir Johnston and Linda Fernandez during a coloring workshop.

Shading a big, bright sun with purple, red, orange, and yellow markers, Fernandez showed her artwork to engage with the group. “Look at that! A hot August sun, just like the one we had yesterday, huh?” Fernandez told the kids, while filling out the white spaces left on her paper.

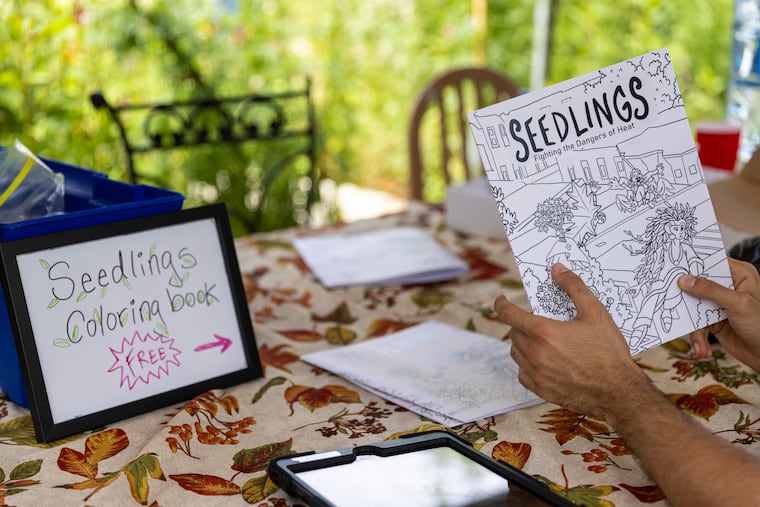

The group was working on Seedlings, a Spanish-bilingual coloring book designed to educate children and adults about extreme heat in Philadelphia.

The workshop and the editorial product, which includes portraits of North Philly streets and landmarks, word jumbles, poems, and questionnaires, are part of a two-year initiative called Heat Response PHL, which brings local artists and neighborhood residents together, to work on a series of solutions to publicize climate change through art, engagement, and education.

The project, created by the Trust for Public Land, started in the pandemic summer of 2020. Environmental artist Eve Mosher was commissioned to coordinate the program. She teamed up with community liaisons Tyrique Glasgow, Sulay Sosa, and Charito Morales, and introduced them to local artists Jenna Robb, José Ortiz-Pagán, Linda Fernandez, and Keir Johnston.

Since then, the group has partnered with nonprofits and social service organizations to meet and engage with residents in Grays Ferry, Southeast Philadelphia, and Fairhill, to learn how to address urban heat islands in their barrios. Trust for Public Land had invested in playground renovations and park beautifications in these three neighborhoods. According to the Philadelphia Heat Vulnerability Index, these neighborhoods also show an average temperature of 2 to 5 degrees higher than the city average.

Mosher, the creator of the HighWaterLine public art installations, said the idea was to use art as a strategy to find ways to interact with neighbors and community members, to understand what they needed to address extreme heat and to learn how they could collectively design solutions that were practical to all.

“Creativity can demystify the truth of climate change and decomplexify how it’s going to impact the world that you imagined you were going to have for yourself, so art can deliver that in a ... more playful way.”

As if using art to address climate change weren’t challenging in itself, Mosher said the pandemic brought its own set of challenges when trying to engage residents with social distancing. She said it pushed artists to use their connections and cultural knowledge within these communities to be able to attract interest.

Historically, heat has been the deadliest weather-related event in the United States According to the National Weather Service, heat, floods, and tornadoes are the weather-related issues that have killed the most people in the country over the last 10 years. In a 2016 report, the CDC said it expected more extreme heat events in coming years due to climate change. The recently published report from the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change linked these weather events — extreme droughts and heat waves — to human-caused global warming and warns of more.

Trees are known for reducing the effects of extreme heat in urban spaces. Tree canopies can make a temperature difference of 15 to 20 degrees in some Philadelphia neighborhoods. According to an Inquirer analysis, residential areas with the least tree canopies generally fall within neighborhoods affected by poverty. These environmental injustices can lead to poor health quality, low economic mobility, and other disparities.

Although the City of Philadelphia has its own heat project in Hunting Park, Owen Franklin, Pennsylvania State director for the Trust for Public Land, said the group has focused the initiative on urban heat to foster more conversations about the ways extreme heat affects Philadelphia residents in marginalized communities. The project received a $300,000 grant from the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage.

Each artist and community liaison has used different engagement tactics to kick around ideas and design climate solutions in each neighborhood.

Fernandez and Johnston, cofounders of Amber Art and Design, produced the “Seedlings” coloring book in collaboration with students from Temple’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture and community members from Fairhill. Some of the youths involved in the project were engaged through the nonprofit Concilio.

Robb and Glasgow in Grays Ferry engaged with the community via a project-specific mailbox at Lanier Park to continue a conversation between local elderly residents and grade school kids. The group is currently developing several projects in the neighborhood, including the expansion of an urban garden and designing a public mural.

Ortiz-Pagán and Sosa in Southeast Philly have been coordinating virtual art workshops with teen residents, neighborhood cleanups, and an exchange program to share recipes of food and drinks that keep locals cool during hot days. These events have led to conversations around building pergolas in residential blocks.

There are 30 team members directly involved in the Heat Response PHL initiative, including an advisory committee, a documentarian, and support personnel with Trust for Public Land. In addition to this group, the artists and community leads engage with dozens of local community members in each neighborhood. The initiative ends in the summer of 2022.

Sosa said the project has helped her and other residents learn about the effects of global warming in urban environments, as most people who live in the area are immigrants who used to live in greener towns, surrounded by trees and shade. Now that neighbors are better informed, she said, the community has a “fuller conscience.”

“Now that we know that our blocks are hot because there are no trees and that our air-conditioners don’t work because our houses don’t have insulation, we are informed. And sharing information is an act of love.”

For residents like Labriana Mitchell, 20, having community members who care about the issues that affect her and her 2-year-old son is a blessing. She moved to West Kensington in April. Despite being new to the neighborhood and to topics about climate and the environment, she said she was moved to participate.

“It’s pretty exciting to find this kind of support, where you learn about these long-term effects while getting to know your neighbors.”