These friends created ‘A Phonebook’ to tell the stories of their favorite Philly businesses

“Shops have special coordinates in the maps of our memories,” said Érica Mukai Faria, one of the artists behind the book.

Nearly two years ago, a group of friends set out to answer the question: What are the stories behind the businesses we love?

The hardware store, the beauty supply shop, the banh mi place.

They had heard many of them already, stories about business owners who had poured their whole lives into their shops and were now struggling to hold onto their spaces because of gentrification, competition with Amazon, and the rise of sponsored review sites like Yelp. If only more people knew about these stories, they thought, they’d come shop at these stores.

That’s how A PHONEBOOK was born.

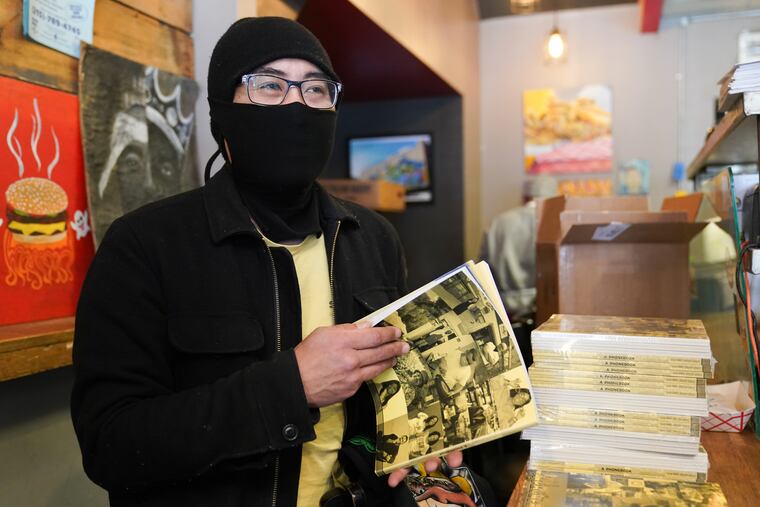

With funding from the Tyler School of Art and Architecture’s Velocity Fund, the project grew into a 144-page book featuring interviews and portraits with more than two dozen local business owners, plus takeout menus and business cards from dozens more. It’s now available — free with purchase — at four Philadelphia businesses: Garden Court Eatery, Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books, Spot Gourmet Burgers, and Molly’s Books & Records. They plan to do a second, larger print run this summer.

The book is a hybrid entity — a mix of journalism, advertising, archive, art — that pays homage to small businesses: “It was just a way to record some folks’ stories in the way that they want them to be heard,” said Andrienne Palchick, one of the artists who worked on the book.

The interviews were conducted in the language business owners felt most comfortable: English, Spanish, Vietnamese. Those not in English were translated and both versions were published so the business owners and their customers could read the interviews. The group behind the book, a collective called Philadelphia Packaging Co., worked with the Vietnamese community organization Vietlead for the business owners who were more comfortable with Vietnamese.

The book includes interviews with owners of businesses on the brink of closure or that are already closed, such as Ernesto Atrisco, who runs Lupita’s Grocery in the Italian Market and is struggling to reopen, and Thomas Sinnison, the owner of Nam Son Bakery, a beloved banh mi spot in South Philly’s Hoa Binh Plaza that shut down in 2019 after developers bought the plaza with plans to demolish it and build condos.

We spoke with Philadelphia Packaging Co.’s Palchick and Érica Mukai Faria about the project.

Why did you decide to do a project about businesses?

Faria: This is going to get a little abstract, but if you ask someone to think about their upbringing or childhood, a lot of times shops have special coordinates in the maps of our memories. They’re locations, and they hold the memory together. It could be the hairdresser you went to or the restaurant your family always went to or the corner store across the street.

From an artistic perspective, sometimes I’m personally more interested in people’s business ventures than their art projects. It’s, to me, so fascinating how much heart and spirit and grit and hard work goes into beginning a business, continuing a business, and persisting through everything. I’m just fascinated by that concept — holding onto a dream and making manifest an actual idea.

Also, so often in this world right now, we’re supposed to be like, “Who are you aligned with? Who’s your group? Are you representing the immigrant community? Or Asian Americans? Or Black people?” And this was a way to be like, “Actually, we’re all poor, working people.”

You started A PHONEBOOK as a way to share stories of places that you loved, to help get the word out about these businesses. Do you also see it as creating a kind of record?

Faria: In retrospect, I think there’s so much utility to it as an archival project. [Andrienne] knows this, I sometimes get really hyped on whatever thing I’m reading, and right now, I’m doing this big rereading of American history, and I think that so often these stories are just swept under the rug and nobody will ever read about them and they’ll become relegated to family histories, these personal, intimate stories that might just be oral traditions but not necessarily recorded anywhere.

One thing that I often hear people say who don’t really like to talk about gentrification is they’re like, “Well, cities change, and change is inevitable.” That’s true. And also, that’s a really convenient way to erase people’s stories. And that is the history of the American empire, just erasing stories.

You’ve talked about this project as an exploration of “off-line connectivity.” Why’d you feel like there was a need for that?

Palchick: We’re on the internet so much, and so much stuff is on our phones and on social media. For folks who have an understanding of those tools, it’s been a very useful tool to market yourself differently, in a way that’s personal. But a lot of the business owners we were talking to are older, or speak English as a second language, people who aren’t connecting with social media in that way. This was a way to connect back to other forms of documenting.

Was it hard to get people to talk to you?

Faria: With good reason, I think a lot of business owners are skeptical of someone being like, “Just tell me about your business, I’m gonna talk about it publicly.” There’s a lot of distrust, not just among business owners, just among communities right now, of like, “What’s your intention? Who are you representing? Who’s funding this?”

It was shocking to people, like, “What do you mean this doesn’t cost me anything?” Some of the most beautiful interviews, in my opinion, they took months of relationship building, months of developing trust.

That reminds me a lot of journalism. Sometimes it’s hard to get the time to build those relationships if it doesn’t immediately turn into a story.

Faria: I don’t wanna say this is journalism because I don’t think we were using the right tactics. Like, having people review what was written about them before it was published. For business owners, I think that’s extremely important because it’s how they’re going to be read, it’s how they’re going to be perceived.

Palchick: That was really important for us, too. You know, it’s a huge responsibility to be putting people’s stories in print and making sure they’re being portrayed in the way they want to be portrayed and having self-consciousness around that.

Faria: We had an example of a small-business owner who didn’t feel like his English was good enough and was embarrassed and he pulled out, and I’m glad we were able to run that by that person so he didn’t feel like he was put on blast in a way he didn’t wanna be.

Yeah, showing people the story before it’s printed is one of those things journalists are taught not to do, in part so that, say, a politician or a CEO can’t go back on their word. But I get why this rule doesn’t make sense to some people, especially if they already distrust the media because they barely get covered in it.

Faria: And [A PHONEBOOK] isn’t really reporting. It’s recording. It’s a little more of a gray area. It is advertising and it is marketing when you’re sharing people’s personal stories in an attempt to bring more people in to their shop.

I think that one of the strongest points of our entire project is probably one of the most confusing parts: You really cannot figure out what it is. And as a mixed queer person, that gives me life. I think that we need more things, more objects in the world that make you question what’s really going on.

What‘s the future of this project?

Faria: Sometimes people are like, “It’ll all pay off in the end” or “It’ll all be worth it.” But that’s not the point. There’s no “hard work pays off” rhetoric here. It’s more like, this is something that we felt needed to be done. We’re not trying to grow this into something larger.

Palchick: We’ve talked a lot amongst ourselves in the collective about wanting this thing to be useful, but I think we all acknowledge that we really don’t presume to be providing back anything that measures up to the amount of service that they’ve provided to us or to our communities. It’s a small way to say thank-you to people.