What Philly-area schools are saying about the SCOTUS ruling to end race-based admissions in colleges

“The Court does say that, for example, qualities of character that might have been affected by race can be considered, but the use of race alone as a factor is illegal," says a Villanova professor.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday ruled that colleges could not use race as a factor in deciding whether students should be admitted, likely one of the most consequential decisions affecting college admissions in the nation’s history.

It marks the second time in a year that the court’s conservative majority has upended longstanding legal precedent; last June it took away a woman’s federally guaranteed right to obtain an abortion.

Colleges locally and nationally have been bracing for the decision, fearing that if schools could no longer consider race as they historically have, it could reduce the number of Black and Latino students at many of the nation’s elite colleges and harm schools’ efforts to create diverse classes.

“It’s a pretty forceful opinion in how widespread it is in the rejection of the use of race in admissions,” said Michael Moreland, a Villanova University law professor who has watched the case closely.

The decision in two cases, one involving Harvard and the other the University of North Carolina, overturn more than 40 years of admissions policy at many of the nation’s campuses, though considering race is already barred in certain states, including California and Michigan.

In those two states, some colleges have reported a decline in Black and Latino students as a result. Pennsylvania and New Jersey both have allowed race to be considered, but colleges here will now have to rethink their approach.

“Many universities have for too long wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the color of their skin,” Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote in the opinion. “This nation’s constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.”

Harvard’s and UNC’s admissions programs “cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause,” he wrote.

Roberts also outlined a way that race still could come into play, particularly in the admissions essay portion of an application: “...nothing prohibits universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university.”

But several legal experts said that window is narrow and doesn’t give colleges much to work with.

“It’s a little bit more oblique in the way the court is allowing it,” said John E. Jones III, a former federal judge who is president of Dickinson College in Carlisle. “Will that lead to as much diversity? That remains to be seen.”

» READ MORE: From 2016: U.S. Supreme Court upholds race-based admissions

Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel A. Alito Jr., Neil M Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett joined Roberts in the opinion, while Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Kentanji Brown dissented.

“Today, this Court overrules decades of precedent and imposes a superficial rule of race blindness on the nation,” Sotomayor wrote. “The devastating impact of this decision cannot be overstated.”

The Equal Protection Clause, she argued, allows the consideration of race to achieve its goal.

“Ignoring race will not equalize a society that is racially unequal,” she wrote. “Equality requires acknowledgment of inequality.”

Reaction to the decision, from the political arena to college campuses, was swift.

“While today’s decision will make our work more difficult, we will work vigorously to preserve — and, indeed, grow — the diversity of our community while fully respecting the law as announced today,” vowed Christopher L. Eisgruber, president of Princeton.

It took decades to undo affirmative action and could take that long to get it back, if it does come back, said Timothy Welbeck, executive director of Temple University’s Center for Anti-Racism. So it really falls on colleges to find other ways to ensure diversity, he said.

“The most viable option is that schools have to get creative in the aftermath and hope that a potential shift in the court in future decades can bring some type of affirmative action back into college admissions,” said Welbeck, a Villanova law school graduate and civil rights attorney who has taught at Temple since 2011.

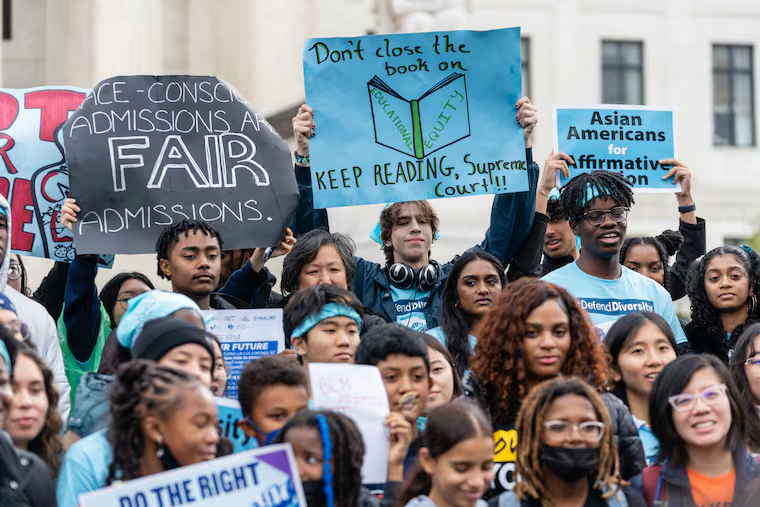

Students and leaders challenge ruling

Democratic members from the Pennsylvania Legislative Black Caucus gathered with their colleagues from the Latino Caucus, the Asian Pacific American Caucus and the Women’s Health Caucus in the Capitol rotunda to condemn the Supreme Court’s ruling.

State Rep. Joanna McClinton, speaker of the Pennsylvania State House, predicted the decision will negatively impact millions of Americans, especially Black and brown students.

“We’re not going to allow courts to be able to deny us opportunities, because there was a day when that happened and we’re still bearing the ugly things from the past,” said McClinton, a Democrat who represents parts of West Philly and a sliver of Delaware County and is the first woman and second Black person to lead the chamber. “We are going to do more for our children and they will not be denied rights. We will not see history repeat itself in these United States.”

Yomi Abdi, a University of Pennsylvania sophomore who is Black, said she “immediately couldn’t focus” at her finance internship when she learned of the Supreme Court decision.

“At Penn, I already feel underrepresented, and I just know this decision is going to lead to less Black students ending up in our incoming classes,” said Abdi, a Wharton student and opinion editor at the Daily Pennsylvanian, the student newspaper. “All of our progress is disappearing.”

But not everyone saw the decision as bad.

“The diversity generated by affirmative action was incomplete,” wrote University of Pennsylvania professor Jonathan Zimmerman. “At our elite universities, especially, we admitted classes that were diverse racially but not economically.”

Now, colleges may look more closely at students from low-income families, he wrote.

Ruling expected to reshape admissions by 2024

Calvin Yang, one of the students who helped to bring the lawsuit against Harvard after being rejected a few years ago, said the decision will make it possible for all people to achieve the American dream.

“At least our kids can be judged based on their achievements and merits alone,” he said a press conference.

In the cases, plaintiffs had accused both Harvard and the University of North Carolina of discriminating against Asian and/or white students through the use of race-conscious admissions policies. The lawsuits were brought by Students for Fair Admissions, a group founded by Edward Blum, a conservative activist who has spent years battling affirmative action policies.

The Harvard case went to the Supreme Court on appeal after U.S. District Court Judge Allison D. Burroughs of Massachusetts in 2019 declared that Harvard’s admissions process was constitutional.

» READ MORE: From 2019: Pa., N.J. college officials laud judge’s decision in Harvard affirmative action case

As recently as 2016, the Supreme Court had ruled in favor of maintaining the use of race in admissions. By a 4-3 vote, the court upheld the University of Texas at Austin’s argument that it needed to consider race to ensure diversity of its student body and that it had exhausted other means of achieving that goal.

But now the court is considerably more conservative: three of the newer justices, Kavanaugh, Barrett and Gorsuch, were appointed by former President Donald Trump. And last October during oral arguments in the case, the tone of the questioning by some justices indicated that the policy was very much in jeopardy.

Plaintiffs argued that Harvard discriminated against Asian American applicants by using subjective criteria to measure positive personality, likability, courage, kindness and other traits, and consistently rated Asian American students lower. Harvard denied the accusations, claiming plaintiffs are using misleading statistics, and defended the use of race in admissions. In the North Carolina case, plaintiffs accused the school of discriminating against white and Asian American students by offering racial preferences to Black, Latino and Native American students.

Cara McClellan, a Penn associate practice professor of law, said the percentage of students from underrepresented groups at Harvard are expected to drop by 50% without race-conscious admissions. She worked on Harvard’s case at the appellate level for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and at that time, Black students made up 14% of Harvard’s incoming class, and Latino students and students from other underrepresented groups made up another 14%. If colleges can no longer consider race, those percentages are expected to drop to 6% and 9%, respectively.

“This could have huge implications,” said McClellan, founding director of the Advocacy for Racial and Civil Justice Clinic at Penn.

For one, employers will have a more difficult time hiring students of color and diversifying their numbers if selective colleges are enrolling fewer of them.

The decision comes at a time in the country’s history when the court should be making moves toward more inclusion, she said.

“They are doing the opposite in terms of rolling us back in time,” she said.

Because colleges already have their incoming fall classes pretty well set, the ruling’s impact will be felt by the class starting in 2024.

Court challenges expected as colleges continue to seek diversity

Legal experts who have watched the cases closely have anticipated it will lead to more legal challenges as colleges test what they can and can’t do under the new ruling. At the press conference, Blum, who led the plaintiffs, vowed more litigation if colleges try to circumvent the ruling.

Colleges have been quietly planning and considering other methods to ensure diversity in anticipation of the court’s decision. They are looking at ways of broadening their applicant pools, targeting certain zip codes that could ensure greater diversity, opening access more broadly to students from lower socioeconomic groups and reconsidering policies, such as giving preferences to legacies, children of alumni.

Princeton’s Eisgruber, a constitutional law scholar who has led the Ivy League university for more than a decade, discussed some of those options in a January interview in anticipation of the court’s ruling. At Princeton, about 23% of undergraduates are Asian American, 8% are African American, and 10% Hispanic, while 6.8% are multiracial and 12% are international.

Like other colleges, race is far from the only thing admissions teams evaluate. Princeton has said it also considers test scores and grades; teacher and coach recommendations; feedback from alumni interviews; interest in and commitment to a field of study or extracurricular activity; exceptional skills and talents, experiences, and background; status as a child of an alumnus or a university staff or faculty member; athletic achievement, musical and artistic talents; geographical and socioeconomic status.The school alsoconsiders national origin; unique circumstances and hardships endured.

Colleges, Penn’s McClellan said, also should work harder with school districts to create mentoring programs and extracurricular opportunities to broaden their pipelines.

“Community-based organizations are going to be key,” Jones, the Dickinson president agreed, citing Heights Philadelphia, which helps students from underrepresented groups get to and through college.

Jones said he understands the argument that plaintiffs have made against discriminating, based on race.

“But the practical effect is that it is going to make it much harder for us,” he said. “Dickinson is very devoted to diversity and I think we lose something if… we can’t enroll as diverse a class as possible.”

At Dickinson, about 5% of the more than 2,100 students are Black/African American, while about 7% are Latino. Nearly 13% of students are international, and about 6% are two or more races or race unknown.

If colleges were to shift to means such as zip codes or socioeconomic status, it’s unclear if the Supreme Court would let that stand.

A new case last month could serve as a future test. An appeals court upheld that a magnet school in Virginia could continue to use its admissions policy, which does not consider race but gives weight in favor of economically disadvantaged students and students still learning English. Critics of the school’s policy said it discriminated against highly qualified Asian Americans.

“It could lead to additional litigation” if colleges try such policies, Jones said. “But I don’t think that’s a reason not to try. Unless, until the court shuts them down, I think they are fair game and ought to be used.”

Staff writers Beatrice Forman, Gillian McGoldrick and Julia Terruso and Pennsylvania Legislative Correspondents’ Association intern DaniRae Renno contributed to this article.