Former Afghan interpreters in Philly watch and worry amid a scary, deadline effort to evacuate their colleagues

At least 300 interpreters and their family members have been killed because of their ties to the United States

Mohammad Azimi knew it was risky to take a job at the U.S. embassy in Kabul, helping to translate contracts, payrolls, and vouchers for the Americans.

Even the local shopkeepers and taxi drivers knew who he was and where he worked, and could easily pass that information to the Taliban. One interpreter recently was dragged from his car and beheaded.

This spring, after six years, Azimi knew something else: It was time to leave Afghanistan.

He arrived in Philadelphia just ahead of what has become a rattling, deadline effort to evacuate thousands of Afghan interpreters who could face deadly retaliation as America’s longest war races toward an end.

“People are trying to get out, but they are in trouble,” said Azimi, 37, who lives in the city’s Mayfair neighborhood with his wife and three children.

The Taliban crushed Afghan security forces, seized major cities, and gained control of the capital, as the Biden administration dispatched 6,000 troops to help evacuate Americans. Afghanistan’s president, Ashraf Ghani, fled the country Sunday as the government collapsed.

In recent years at least 300 interpreters and family members have been killed because of their ties to the United States, according to No One Left Behind, a nonprofit that seeks to speed the resettlement of Afghans who assisted the Americans.

About 200 translators landed in this country last month as Taliban forces advanced ahead of the scheduled Sept. 11 U.S. withdrawal, and more are coming now.

Under Special Immigrant Visas, or more simply SIVs, translators are being moved to three destinations: the United States, American facilities in other countries, or homes in countries where they can more safely finish their applications.

The vetting process is extensive. So are the complications, with visa applications derailed over what can seem like technicalities.

For instance, Afghans who were employed by or on behalf of the U.S. government must submit a letter of recommendation from their supervisor — who has to be a U.S. citizen. No matter how closely the person’s work or company was allied with the American war effort, if their direct boss or the person running the firm was not a citizen, then they’re ineligible for an SIV.

“We have these narrow gates,” said Linda Robinson, director of the RAND Corp.’s Center for Middle East Public Policy and the author of Tell Me How This Ends: General David Petraeus and the Search for a Way Out of Iraq. “They expanded the gates last week, but it’s not enough if the goal is to protect all those who are presumably at risk.”

She referred to the Aug. 2 State Department announcement that thousands of Afghans who worked for the United States, for a government-funded project, or a U.S.-based media company or NGO would be eligible for resettlement as refugees in this country. The program applies to those who don’t qualify for SIVs.

But the government has no plans to support their evacuation, which means newly eligible Afghans must find their own way out of the country to safety, even as the Taliban seizes border posts and crossings.

Much of the U.S. focus has been on interpreters whose work made them “publicly known targets,” and to whom the U.S. owes a clear moral responsibility, Robinson said. But they’re not the only ones in danger of reprisals.

People may imagine the interpreters as fatigue-clad soldiers, set beside American troops to translate orders, communications, and conversations on the battlefield. And many do exactly that. But they also work in scores of jobs spread throughout the in-country arms of federal agencies and contractors.

In those positions they handle everything from servicing cars, to booking plane tickets, to translating complex financial documents and even assisting at Army PXs, the post exchanges that serve as supermarkets and retail stores.

Interpreter Fahim Sekandari worked years — often under fire — for the Army Corps of Engineers. It was dangerous, but it was a reliable job with good pay in a country where employment prospects are bleak.

“I liked the U.S. Army,” said Sekandari, who came to Philadelphia on an SIV in 2018. “Good discipline, and very respectful.”

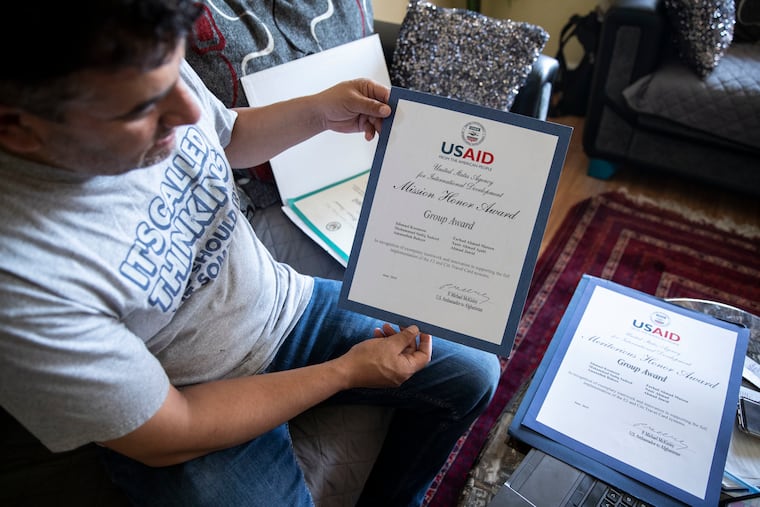

Today Sadiq Sadeed is office manager at Philadelphia-based HIAS Pennsylvania, where he helps immigrants start new lives in the United States. Before settling with his family in Mayfair in 2019, he worked in the U.S. embassy in Kabul as an interpreter for USAID, the development agency.

He’s worried about his brother who is still in Afghanistan, working for a worldwide food-and-services supplier that provides 150,000 meals a month to NATO forces. His brother’s supervisor is not a U.S. citizen, blocking the path to a Special Immigrant Visa. A friend faces the same bar.

“Their lives are threatened,” said Sadeed, 40, but there’s no way they can qualify for a visa.

Two decades ago, Sadeed was finishing high school as American troops arrived, sent by President George Bush to topple the Taliban after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The insurgents were ousted but never eliminated.

Sadeed studied English, which had to be kept secret, then ran a small education center. He got a job at a company that serviced vehicles for the Afghan National Police, moved to a construction position at another firm, and eventually to an office manager’s post at the Netherlands embassy.

As the Dutch wound down their forces, he found a job with the Americans.

In the embassy he worked as a travel supervisor, scheduling passages on flights, handling visas, and providing orientations for staff coming from Washington.

The only certainty was uncertainty. During the hiring process, U.S. government agents routinely interviewed prospects’ friends and neighbors, and even local government officials and police, effectively spreading word of their applications. Then, once hired, new employees were told to keep quiet about their work.

Even approaching the embassy gate could be dangerous, Sadeed said, because of the uncertain allegiance of the police who worked there.

“People who one day are providing you the security to work with the U.S. agency,” he said, “the next day they may work for the antigovernment militia.”

Azimi’s title with USAID was financial management specialist, a position in which he handled complicated monetary matters. In this country, his master’s degree and nearly 20 years of accounting experience have brought only a food-service job.

Still, he said, leaving was the only safe choice.

“People at the embassy were telling me, ‘Don’t wait,’ ” he said. “ ‘Don’t wait for any organization to take you. Take your tickets and go.’ ”