North Philadelphia elementary school to remain closed due to asbestos concerns

“No level of asbestos is safe. Those fibers are microscopic. What happens if she gets some disease when she’s in high school?”

A North Philadelphia elementary school will remain closed at least through Jan. 13 to address concerns about damaged asbestos in heavily trafficked areas, including several classrooms.

The news came Thursday as worried McClure Elementary School parents, staff, and students pushed the Philadelphia School District for answers about a growing environmental crisis in schools across the city.

The decision to close McClure to students was made Dec. 19. At first, students were supposed to return Thursday, but that date has been pushed back as district and teachers union environmental experts identified more troublesome asbestos in the school.

Jim Creedon, the district’s interim director of facilities, operations, and capital projects, said at a meeting for the McClure community that the school system will dispatch crews to abate damaged asbestos in McClure classrooms, stairwells, and other areas, and hopes that the work will be complete by Jan. 13.

But “if something unusual would come up in the next week or next couple of days, then we do have to look at other alternatives,” Creedon said.

“We’re erring on the side of safety,” said Amelia Coleman Brown, the assistant superintendent responsible for McClure.

A decision about Carnell Elementary, the Oxford Circle school also closed in late December, has not yet been made, officials said.

The district has had to shut six schools and an early childhood education center because of asbestos issues so far this school year, drawing criticism for its handling of environmental hazards and the way it has communicated with affected communities. In the case of some schools — Benjamin Franklin High, Science Leadership Academy, T.M. Peirce Elementary, and Pratt Early Childhood Center — students and staff have had to be relocated while cleanup is conducted.

At the McClure meeting Thursday night, officials said that they could likely finish some remediation but that some work — including handling asbestos in the gym — will not be complete by Jan. 13. After students return that day, the gym will be sealed off, with asbestos remediation to be undertaken at night, when students are not in the building.

That students and staff would be expected to be inside the building while asbestos abatement occurred stirred the more than 100 people who gathered inside the auditorium of nearby Clemente Middle School.

“No!” some shouted.

Rosalind Lopez, whose granddaughter is a kindergartner in Room 109, one of the affected classrooms, said the girl has been sick all school year, and now she wonders if it’s related to McClure’s environmental conditions.

“No level of asbestos is safe. Those fibers are microscopic. What happens if she gets some disease when she’s in high school?” asked Lopez, who told officials that she thought the asbestos situation would be handled differently if she and other McClure families were wealthy.

Asbestos is not dangerous if undamaged, but when damaged, tiny, cancer-causing fibers can release into the air and can become ingested.

Jasmine Santiago, mother of two children who attend McClure, said many parents now want to pull their children from the school.

“If this asbestos is something that’s been there for a long time, I worry,” Santiago said.

Pearline Sturdivant, a former district teacher, said that the public has been aware of environmental hazards inside city schools for years, and certainly since the publication of Toxic City, an Inquirer series that highlighted asbestos, lead, and other problems inside schools.

“Why wasn’t the work done then?” Sturdivant asked. “This should have been taken care of.”

» READ MORE: Read more: Missed asbestos, dangerous dust

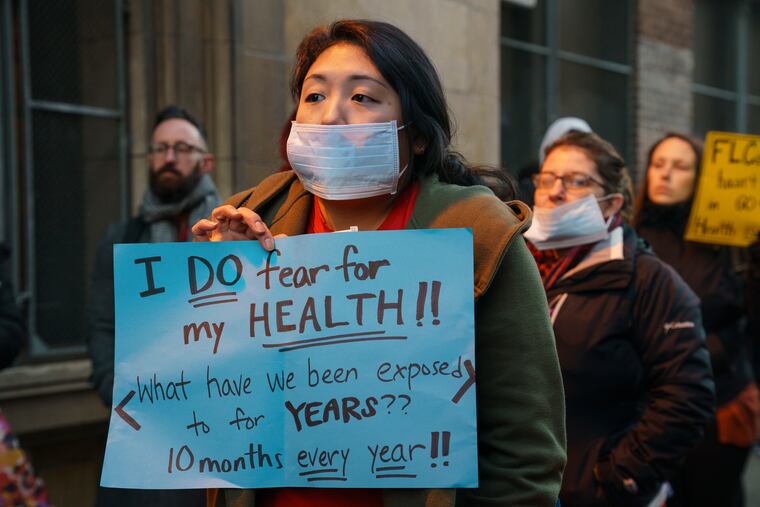

Earlier Thursday, staff, students, and parents at Franklin Learning Center rallied outside their school, protesting environmental conditions inside the building. FLC was shut down in late December after officials found damaged asbestos representing an “imminent hazard” at the school on North 15th Street. Staff there said they had been reporting environmental hazards at the school for years, but their concerns were ignored until December.

The staff said they were promised that a long list of tasks would be completed before the building reopened and that many jobs were incomplete. Teachers have said that in addition to the asbestos, the school has been plagued with a leaking roof, exposed insulation, flaking paint and plaster, and a dirty ventilation system.

» READ MORE: Read more: Toxic City

“The school still feels like a work site; there were tons of teachers who went into their classrooms and had chips of paint and dust all over their desks,” said Louis Fantini, an FLC social studies teacher. He said special-education students had to be relocated from their resource room because paint chips littered its floor.

“It all feels very rushed, and we just want to draw attention to the fact that even though these conditions have been normalized, we won’t accept them as normal,” Fantini said.

Environmental woes at FLC are not new; students at the school walked out of their building in the 1990s over asbestos concerns. School staff say they and their students have coped with elevated rates of asthma, allergies, cancer, and autoimmune disorders.

Megan Lello, a district spokesperson, said the school system worked at FLC over the break on not just asbestos issues, but also painting, plumbing, and roof repairs.

“The district continues to work directly with the city, elected officials and other organizations to confront the challenges it faces, such as deferred maintenance costs associated with its aging infrastructure,” Lello said in a statement. “The district remains committed to providing safe, healthy and vibrant learning environments for all students and staff. They deserve nothing less.”