Five interesting facts from Ken Burns’ new documentary on Ben Franklin

'Benjamin Franklin' airs on WHYY on Monday and Tuesday at 8 p.m.

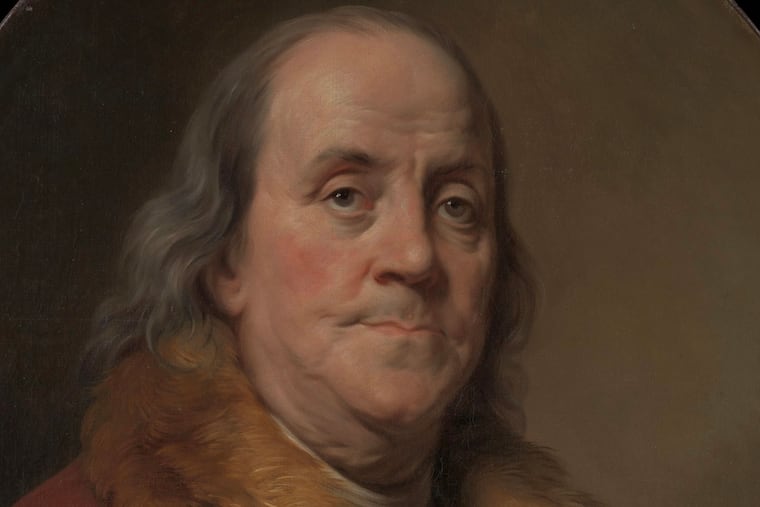

As a printer, publisher, writer, inventor, scientist, diplomat, and civic leader, Benjamin Franklin is a difficult historical figure to characterize. But a new Ken Burns documentary from PBS attempts to do just that.

Benjamin Franklin explores Franklin’s life from his humble beginnings in Boston, to his work building the newly established United States of America, and everything in between. And split across two episodes totaling four hours, it’s a doozy — but if any historical figure deserves that in-depth of a look, it’s Philadelphia’s favorite son.

» READ MORE: Ken Burns on Ben Franklin’s legacy: It’s complicated | Opinion

So, we sat down and watched it and compiled some takeaways for the time-crunched and history-averse. But if you want to watch, it airs locally on WHYY on Monday and Tuesday at 8 p.m. Check out our list below:

Franklin was a teenage runaway

Born in 1706 in Boston, Franklin signed a nine-year apprenticeship with his brother James at age 12, legally indenturing him to work at James’ print shop. In 1721, the shop started publishing the New England Courant, which, unknown to James, printed Franklin’s written works under the name Silence Dogood. James was quickly jailed for the paper’s content, and when he was released, Franklin confessed to his pen name, causing arguments and physical fights between the two.

Franklin, then 17, decided to run away and break his legal obligations to his brother. He left Boston on a ship heading south, lying to the captain that he had gotten a girl pregnant and needed to leave. After 11 days, he arrived at the Market Street Wharf in Philadelphia.

Among his first acts in town was falling fast asleep at a Quaker church service, and one of the attendees woke him up. Then, when passing a house on Market Street, he “exchanged glances” with a young girl who would later become his common-law wife, Deborah Read.

» READ MORE: 5 people Philly should hype instead of Ben Franklin | Opinion

His relationship with son William was … not great

Franklin’s relationship with his only son, William, who was born out of wedlock to an unknown woman, ended bitterly, with the pair estranged for years. William was eventually named the final royal governor of New Jersey, and became a loyalist during the American Revolution, with Franklin moving in the opposite direction and becoming a “fervent revolutionary” and patriot. Understandably, that drove a serious wedge between them, and they went years at a time without seeing or speaking to one another.

Post-Revolution, the world’s first-ever air-mail letter was sent via hot air balloon to Franklin’s grandson, Temple — and it came from William, a father whom Temple had never met. William wanted to establish a relationship with Temple, and reconcile with his own father — but Franklin wasn’t having it. In response, Franklin wrote to William that he could “confide to your son the family affairs you wished to confer upon with me. … I shall hear from you by him.”

By summer 1785, the pair had not seen each other for a decade, and finally met in England. Franklin, the documentary says, treated it like a negotiation, and demanded that the deeds to William’s properties in America be turned over to Temple. William agreed, and they never saw each other again.

Franklin had some high-profile haters

While Franklin was an international celebrity in his lifetime, there were a couple notable figures who were decidedly not in the fan club.

Fellow founding father John Adams wrote in 1783 that Franklin’s “whole life has been one continued insult to good manners and decency.” He added that he wanted Franklin to retire from public service, and instead spend his time “repenting of his past life, and preparing, as he ought to be, for another world.”

King Louis XVI, meanwhile, was both amused and annoyed with the massive popularity Franklin enjoyed in France when he arrived there in late 1776. As the story goes, the king had a chamber pot with Franklin’s likeness emblazoned inside of it, mostly as a way of saying “enough already,” the documentary says.

He did not become an abolitionist until late in life

As a younger man, Franklin owned several enslaved people, and ran ads for the sale of them in his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette. During his time in England, an enslaved man named King ran away, and Franklin took out an ad in a local paper offering a reward for his return.

His opinions on slavery did not begin changing until late in his life, and he did not publicly address the issue until 1788, after the Constitution was signed. After that, the documentary says, the last act of his public life was a treatise against it.

“You will be pleased to countenance the restoration of liberty to those unhappy men who alone in this land of freedom are degraded into perpetual bondage,” Franklin wrote in a petition to Congress in February of 1790, “that you will devise means for removing this inconsistency from the character of the American people.”

The House of Representatives voted 29-25 that Congress had no authority to interfere on the issue of slavery. In the Senate, it was tabled without discussion.

At his funeral, admirers flooded the streets of Philly

Franklin died in 1790 at age 84 after an abscess burst in his lung. His funeral on April 21 of that year brought out 20,000 people to follow the procession from his home on Market Street to Christ Church Burial Ground, where he was interred alongside his wife. At the time, according to current estimates, Philadelphia’s population was about 28,000, and it was the largest crowd the city had ever seen.

More than six decades earlier, Franklin had written his own epitaph that read:

“The Body of B. Franklin, Printer; like the Cover of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be wholly lost; For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition, Corrected and amended By the Author.”

Ever the editor, by the time of his death, Franklin had cut that grand statement down. Today, it simply reads: “Benjamin and Deborah Franklin.”