Pennsylvania officially abolished slavery in 1780. But many black Pennsylvanians were in bondage long after that.

How forced labor persisted in Pennsylvania until at least the late 1840s.

The moment that Pennsylvania abolished slavery came at a time of transitions. It was the first day of March 1780, and an early thaw seemed to be breaking the grip of an unusually harsh winter. The War of Independence was still underway, but it had been two years since British troops pulled away from Philadelphia. Abolitionists were calling out the contradictions of enslaving Africans in a nascent nation that had spilled its young blood in the name of liberty. In the commonwealth, attitudes were shifting.

“It is not for us to enquire why, in the creation of mankind, the inhabitants of the several parts of the earth were distinguished by a difference in feature or complexion," read the abolition act passed that day in Pennsylvania. "It is sufficient to know that all are the work of an Almighty Hand.”

With that measure, the Pennsylvania legislature became first in the colonies to pass an abolition law. But lawmakers never actually put forth provisions emancipating those already in bondage.

Although Pennsylvania would be heralded throughout history for its bold stand, freedom here didn’t arrive categorically. The Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery allowed the institution to survive, in various guises, for decades.

Enslaved people born even the day before passage could still be kept in bondage for life. The last enslaved Pennsylvanians wouldn’t be freed until 1847.

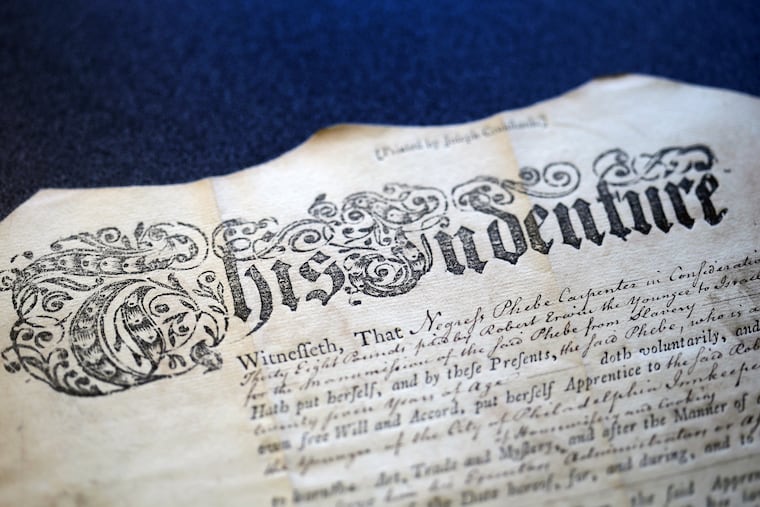

And the children of enslaved people could be bound through indenture — wage-free labor for a set time as defined by contract — until they reached age 28. Historians estimate that 2,000 or so people, most of them African Americans, were indentured in the city by 1800.

“Philadelphia’s referred to as a way station between enslavement and freedom,” said Weckea Lilly, a researcher at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Indentures, as many historians have argued, blurred the boundaries between servitude and slavery. In Pennsylvania, the practice persisted until at least the late 1840s.

Douglas Harper, a Lancaster-based historian, said enslavement was becoming less economically advantageous in Pennsylvania when the law passed.

“The moral arguments are mainly what they put forth," he said. "But there was a practical side of it.”

Indentures for white people in Early America were often signed for orphans, apprentices and immigrants paying back the cost of their passage. Among white indentured servants, it was common to see term lengths of four or seven years. Servitude limits for white youths experiencing hardship would often stop at age 18 for white women and 21 for white men. Since black Pennsylvanians could be indentured for longer terms, many historians contend that the practice more closely resembled slavery than the experiences of white bond servants. Plus, historians Gary B. Nash and Jean R. Soderlund have written, “many laboring people did not live to see their 30th birthday, and physical depletion among laboring people often began in their 30s.”

Many indentures stipulated apprenticeships of some sort. Contracts would order training for literacy or a trade. Indentured people were often given two suits as compensation upon release, with the common caveat of “one whereof to be new.”

In 1826, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed that indenture could only pass down from enslaved parents. Experts note that indentures in the state declined by the 1820s.

Ironically, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society assisted indentures. In early America, progressives considered indenturing more humane than sending someone to the poorhouse. The last indenture registered in Abolition Society records ended in 1844. A contract gathered by the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh shows that a 6-year-old girl was indentured in Pittsburgh with her release set for 1847.

While emancipations and indentures “might have been some measure to kind of heal some of the ravages of slavery,” said researcher Lilly, they "didn’t always do the work because of the inability to define properly what the black person would be to the nation.” The Abolition Society, he continued, “didn’t know exactly what to do for the most part, but they did what they thought was best.”

While historians widely agree that black indentured people weren’t free, these scholars take different stances on how to discuss the institution. Where one calls it “term slavery,” another calls it “semi-freedom.”

Some of the bondholders were themselves African American. Nicholas Wood, a historian at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Ala., pointed out that an indentured person ran away from Richard Allen’s home, much to Allen’s dismay.

Indentures were essentially a compromise to curb the financial losses of families who enslaved. These contracts weren’t only attractive to enslavers who wanted captive Africans. There were financial benefits for those with changing perspectives around slavery, Nash and Soderlund have written. Indentures provided enslavers a chance to distance themselves from slavery, but still reap profits from bondage.

Cato Collins was bound through indenture when he was nearly 13 in Philadelphia, according to his 1784 indenture contract, housed at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. He was enslaved by John Collins, a delegate to the Continental Congress who would later become governor of Rhode Island. According to Wood, the delegate presumably brought Cato Collins to Philadelphia, then freed him. Cato Collins was indentured to a local Quaker man.

Cato Collins not only impressed the Quaker bondholder, Wood said, but also employers, who left him money. He eventually became an oyster man who organized social events and entered the black Philadelphia elite, distinguishing himself as an abolitionist. Many previously indentured Pennsylvanians didn’t enjoy that level of success.

Many African Americans in the commonwealth were cottagers, or people who worked for landlords in exchange for housing on yearly contracts — a system that has drawn comparisons to sharecropping in the American South.

As detailed by Nash and Soderlund, the ranks in black society in this era varied from day workers to artisans, tenant farmers and those who owned their own land to well-off businessmen. But, they wrote, “few black families rose above cottager status” following abolition.

Cato Collins, Wood observed, was literate as a youth and wrote well as an adult. In A Fragile Freedom, Rutgers historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar wrote that many indenture contracts called for just three to six months of education. She cited a toddler that a poorhouse bound out through indenture. That bond ordered that the young child “be taught to read if capable of being taught.”

Indentured people in rural settings, where farm work prevailed, were even less mobile than the unfree laborers in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

Border areas, like those in Chester and Delaware Counties, may have had muddied practices, Harper said, since slavery was legal in Maryland and Delaware. And indentures in Southwestern Pennsylvania may have been more harsh, he argued, for that region saw more enslavers from Virginia.

While male servants could aspire to learn trades and become craftsmen, Armstrong Dunbar wrote, craftswomen weren’t as welcomed. Black women labored domestically with few options.

If bound until 28, a black indentured woman might have a harder time getting married than a white indentured woman who was released at 18, Wood explained. Pregnancy could lead to a bondholder extending an indenture term.

Indentured people also experienced family separation. For Teeny, an enslaved woman in Philadelphia, her freedom in 1786, came at a cost: it would be voided if she had more children, according to the document that freed her. Historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar wrote that marriage, considering contraception in that era, would risk her freedom. Armstrong Dunbar figures this stipulation was to diminish Teeny’s family responsibilities so she could work more. At that point, Teeny already had boys ages 2 and 4. The youngest was bound out to another household. Teeny was consigned to servitude.

Many details of the lives of indentured Pennsylvanians remain mysteries. Historian Michael Kearney of Wayne has been seaming together documents around a cohort of enslaved people rescued by Navy sailors off the coast of Cuba and brought to Philadelphia. The 126 captive Africans who survived were indentured. For the most part, they became scattered throughout the Philadelphia area.

“The fact that some of them disappeared from the record is a maybe a sign that things didn’t go so well for them,” Kearney said.

Kearney has retraced some of the steps of Samuel Ganges, one of the Africans who had been saved, then indentured. He was born in Guinea, circa 1777. After arriving in Philadelphia in 1800, he was indentured to Edward Brinton Temple of Pennsbury for four years, a common term for black people bound in their 20s. The indenture directed that Temple train him in farm work and teach him how to read and write.

Ganges stayed in Chester County for the rest of his life. He was a servant in his 70s, but later moved to the Chester County poorhouse, where he died in 1868.

Ganges was survived by one son, named George, who became an ice cream shop owner in West Chester and fathered at least eight children.

Joseph Mitchell, a high-performance coach based in Brewerytown, is Ganges’ great-great-grandson, according to Kearney. Mitchell, 63, said he was surprised to learn of an ancestor who had been indentured. Mitchell said that he has been fortunate not to have experienced much discrimination in his life and that it was difficult to imagine his ancestor’s reality.

“I can’t get emotional about these things, for my own sanity,” Mitchell said. “It does sound a little bit out of integrity for Quakers to be saying, ‘We have no slavery,’ then to have this indenture piece. It doesn’t sound right to me.”