Having black male teachers makes a difference. This Philly school shows why.

At this Philadelphia public school, half of the teaching force is now made up of men of color — a proportion that many schools struggle to achieve. The shift has made a difference in attendance, attitudes and building climate.

A knock on Charles Williams’ door interrupted the quiet of the prep period for the seventh-grade social studies teacher at Bethune Elementary. Outside the classroom stood a young man who sometimes stopped by just to talk to someone he trusted and respected.

Williams shook the boy’s hand, told him he was busy at the moment but would make time for him later and urged him to come back. When the door closed, Williams smiled.

“I never thought of myself as a role model,” the teacher said. “But I show up every day, I’m prepared, I’m professional, and that makes a difference. I love that.”

At Bethune, a public school in North Philadelphia where three-quarters of students are black, an astonishing half of the teaching force, like Williams, are men of color. Historically, the school has struggled academically, but the shift in its teaching force has made a difference in attendance, attitudes and building climate, said Principal Aliya Catanch-Bradley.

“It might not always translate to an A tomorrow, but in self-esteem, in resilience, in grit — in things you can’t measure — it matters,” said Catanch-Bradley, who leads a school of 650 students in grades Pre K-8. “Kids don’t make it without those things.”

Nationally, just 2 percent of the American teaching force is made up of black men, though research shows that kids of color have better academic outcomes when their teachers are diverse. A recent study found that black children who have one black teacher by third grade are 13 percent more likely to enter college, and those who have two black teachers by third grade are 32 percent more likely to do so.

In Philadelphia, the superintendent has established a goal of increasing the ranks of black male educators. Five percent of the Philadelphia School District teaching force is made up of black men. Bethune’s efforts have drawn a national spotlight — chronicled earlier this year by NBC News.

Herman Douglas has taught at Bethune for 10 years; at first, he was one of just two black men. A few years ago, the school principal at the time began recruiting more men of color as a way to better reflect the student body.

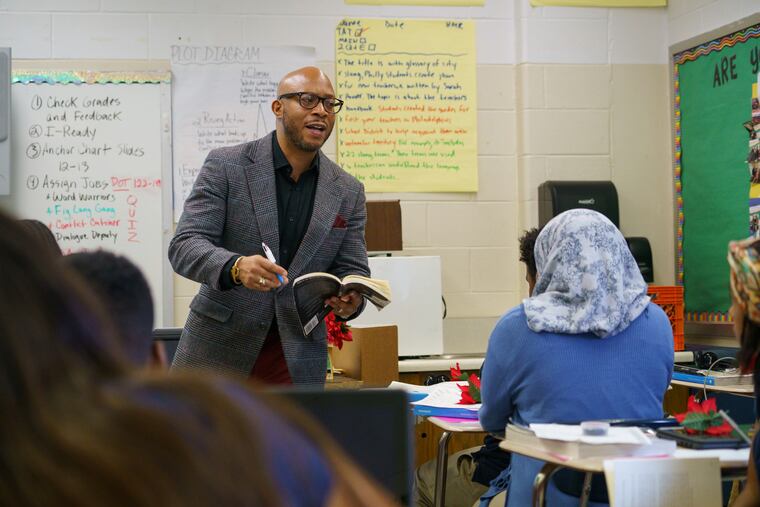

“We want to be the light in North Philadelphia,” said Douglas, a seventh-grade English teacher. “We want to show people how it’s done.”

Douglas is president of “Men of Bethune,” a group of teachers, support staff and parents launched this year in recognition of the school’s growing group of black male staffers. They meet weekly, brainstorming ways to lift up students and engage the community. Their motto is a quote by Mary McLeod Bethune, the trailblazing African American educator and stateswoman for whom the school is named: “Enter to learn, leave to serve.”

Every Thursday, the Men of Bethune wear suits. They held an event this year for the school’s girls, handing each a rose and reminding them to never let anyone treat them as anything less than a queen. Its members advise after-school clubs and run a basketball team that plays in a league on weekends.

Last week, the group sponsored “Bethune’s Barbershop,” bringing volunteer barbers and hair stylists to the school to provide free haircuts for students. The student lounge was a hive of activity, with 10 professionals set up at makeshift stations — milk crates and pillows atop blue student-size chairs. The sounds were joyous: the buzz of clippers, the click of scissors, ooohs and aaahs from students looking in the mirror, all set to Christmas music.

Darnell Johnson, a second-grade teacher, was in perpetual motion: As the organizer of the event, he ran from room to room, pulling students whose parents had asked for haircuts for them, laughing with children delighted at their new looks.

Johnson came to Bethune last year, intrigued at the idea of teaching in a community that was so intentional about embracing diversity.

“The kids need it,” Johnson said. “A lot of our kids don’t have father figures — we’re those role models for a lot of kids who need them.”

Academics must be paramount, said Catanch-Bradley, but removing barriers' to kids' success is the first step in a neighborhood where the median household income is $18,557 and home lives are often complicated — some are involved in the foster-care system; many have witnessed violence; some have family members incarcerated.

“Young black males are sometimes in danger,” the principal said. “For them to see strong black men in positions of power and intellect — that’s important.”

Just ask seventh grader Chris Briggs, 13. Does it make a difference that Douglas calls him and his classmates “king” and “queen” and tells each one “you’re great” when they walk into the classroom?

“It does,” said Briggs. “He wants us to work hard, and he wants us to be the best we can be. So we are.”

Williams, the social studies teacher, was 10 when he lost his father to the streets of Newark, N.J. He knows teachers don’t have to be black to help black children — his own favorite teacher was a white man who not only insisted Williams apply for admission to a magnet high school, but showed up at his grandmother’s house to drive him to the placement test.

But when he tells his students that they can make it to and through college, it means something different coming from a man whose story is perhaps not so different from their own.

“There’s just a cultural relevancy,” said Williams.

Quamiir Trice teaches fourth grade at Bethune. His story — a rise from drug dealer to meeting President Barack Obama as a promising college student — is no secret to his pupils.

After a rough first year of teaching, Trice returned to Bethune because, he said, he felt like there was more work to do. And this year, he said, things are clicking. He started an after-school program for fourth-, fifth- and sixth-grade students — not the academic superstars, but the ones who need a little extra something. The children focus on academics, but also entrepreneurship.

“We’re figuring out new ways to engage students,” Trice said. “And now, they never want to leave school.”

Correction: A previous version of this story identified teacher Darnell Johnson by the wrong last name.