$200M lawsuit over bronze Brâncuși pits Warhol friend against Philly high society scion

“The story is ‘Grand Theft Brâncuși,’” said Manhattan art collector Stuart Pivar. “Philadelphia lawyer hornswoggles savvy New York collector out of $100 million. That’s my story. That’s what happened.”

The works of the late Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși are prized by fine art collectors for their clean, modernist lines and deceptive simplicity.

But one of his most celebrated pieces, Mademoiselle Pogany II, a bronze, egg-shaped bust of a young Hungarian artist, has ignited an increasingly messy custody fight between two noted figures of the East Coast art world.

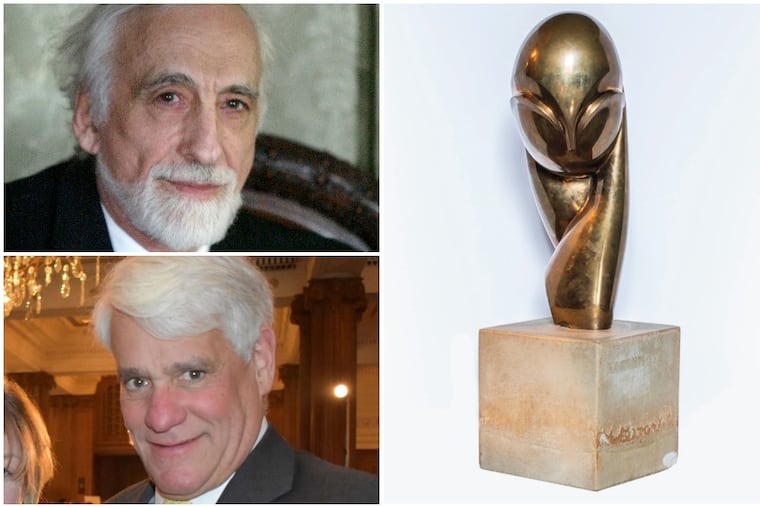

In a lawsuit filed this week in New York State Supreme Court, Manhattan collector Stuart Pivar, a one-time friend of Andy Warhol, says he was swindled out of a 1920 cast of the sculpture by John H. McFadden, a Philadelphia lawyer, arts patron, and scion of a prominent Main Line family.

McFadden, the suit alleges, offered to broker a sale to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, only to keep the sculpture — which Pivar estimates is worth more than $100 million — as soon as he had it in his possession.

McFadden declined to address those claims when contacted by The Inquirer this week.

But Pivar, a participant in more than a few tabloid-worthy art world scraps, was more than willing to set the scene.

“The story is ‘Grand Theft Brâncuși,’ ” Pivar said in an interview. “Philadelphia lawyer hornswoggles savvy New York collector out of $100 million. That’s my story. That’s what happened.”

A litigious collector

That McFadden, 72, would find himself at odds with Pivar, 88, in court will come as little surprise to anyone familiar with the collector’s litigious history.

Pivar’s long-running feud with the board of the New York Academy of Art, which he cofounded with Warhol in 1982, has generated dozens of headlines, a number of lawsuits, and an embarrassing public spat in which he was forcibly ejected — “ass over teakettle,” as he told the New York Post — from the academy’s annual benefit in 1993.

McFadden’s sister, acclaimed fashion designer and New York socialite Mary McFadden, a longtime friend of Pivar’s, introduced the two men earlier this year.

That led to a lunch invitation at John H. McFadden’s Ritz Tower apartment in Manhattan, where the lawsuit claims the attorney first pitched his services as an estate lawyer to set up a foundation to administer Pivar’s prodigious art collection.

Pivar earned a fortune in the 1960s with a group of plastic mold companies he founded. But his true passion is the ever-growing assortment of figurative art, Renaissance furnishings, modern ceramics, and other pieces that fill the rooms of his baroquely furnished home.

He befriended Warhol in the early ’70s, and until the artist’s death in 1987 their near daily habit of scouring Manhattan galleries together drew regular media attention.

When a New York Times reporter, invited into Pivar’s apartment in 2004, remarked upon the several bronze casts by sculptor Auguste Rodin that she found stashed almost as an afterthought under a 16th-century harpsichord, the collector simply shrugged.

“Everyone has a Rodin,” he said.

A prominent family

McFadden, meanwhile, was no novice in the circles in which Pivar traveled.

He hails from a prominent Philadelphia family as steeped in art patronage as it has been in the worlds of American commerce and politics over the last two centuries — one that also can lay claim to a Kennedy-esque penchant for dramatic demises.

Great-grandfather George H. McFadden Sr. founded one of the world’s largest cotton brokerages in the 19th century.

The extensive art collection bequeathed to Philadelphia by McFadden’s great-granduncle and namesake, John H. McFadden, prompted, in part, the construction in the late 1920s of the neoclassical edifice that still houses the city’s Art Museum on the Parkway.

McFadden’s grandfather, George H. McFadden Jr., served on the armistice committee in Paris that brought an end to World War I. Afterward, he bought and refurbished Radnor’s opulent Bloomfield Estate, the Trumbauer-designed, 16th-century French-style château where he died a year later, electrocuted in a steam room that he installed himself.

McFadden’s father, Alexander Bloomfield McFadden, was killed in an avalanche while climbing the Rockies in 1948. Uncle George McFadden III, an archaeologist, was involved during World War II with the Office of Strategic Services, precursor to the CIA, then drowned off the coast of the Greek Island of Kourion in 1953.

McFadden’s brother, venture capitalist George McFadden, died in a 2008 plane crash in Texas.

For his part, John H. McFadden has earned his living as an attorney in Philadelphia, New York, and London. He and his wife, Lisa D. Kabnick, a senior adviser at the law firm Pepper Hamilton, have sat on the boards of the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Art Museum, the Academy of Music, the Curtis Institute, and the Barnes Foundation. (Kabnick is also vice chair of The Inquirer’s board of directors.)

So when McFadden proposed a sale of Pivar’s prized Brâncuși, the New York collector said he listened.

“This was the brother of my lifelong friend,” he said. “He told me he was on the board of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.”

A suspect deal?

What happened next is in dispute.

According to Pivar’s lawsuit, McFadden in May suggested enticing the Art Museum — which houses one of the world’s largest collections of Brâncuși sculptures — into buying Pivar’s cast of Mademoiselle Pogany II.

Saying the piece could fetch as much as $100 million and that it would be “advantageous to them both” if the sale was made under McFadden’s name, the lawyer drafted a contract to transfer ownership to himself for a nominal price of $100,000, Pivar claims.

Pivar admits he signed the document. But he insists he and McFadden agreed that it was an on-paper deal only and that proceeds of any sale to a real buyer would be returned to him.

Yet when he followed up with McFadden a few days later, Pivar says, he received only a curt email reply.

“He said the deal with him was final,” Pivar recalled. “And the statue would remain in his possession forever.”

Pivar learned later that McFadden’s term on the Art Museum’s board had ended seven years prior. (McFadden remains on two advisory committees for the museum, according to its most recent annual report.)

McFadden declined to be interviewed for this story, but when contacted by The Inquirer earlier this month, he acknowledged purchasing “an item” from Pivar and added: “I paid him full value for it.”

Pivar has asked the New York court to award him $200 million — half for his estimate of the statue’s value and $100 million more for tortious interference.

Whether the Brâncuși in question is worth that much remains an open question.

An uncertain value

Several modern art experts contacted by The Inquirer said it was impossible to appraise Pivar’s statue without inspecting it. Still, all of them described Mademoiselle Pogany II as one of Brâncuși’s most recognizable works.

By the time of his death in 1957 in Paris, Brâncuși was widely acclaimed as one of the pioneers of modernist sculpture. But when he carved his first iteration of Mademoiselle Pogany in marble in 1912 — depicting an egg-shaped, blank-eyed woman with slender hands cushioning her face — he had only just begun to draw attention from collectors and critics in Europe and the United States.

The first bronze cast made a splash the following year during Brâncuși’s first exhibitions in America, and additional versions were created in marble and bronze over two decades.

The Art Museum has one in its permanent collection, while others are housed in the Getty Museum in Los Angeles; the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, N.Y.; and the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven.

A bronze cast of the statue sold for $7 million at a New York auction in 1997. But Abigail Asher, partner at New York art advisers Guggenheim Asher, said that work could be worth far more today.

Other Brâncușis recently netted record-breaking prices — including the $71 million paid for a different work by the sculptor at a New York auction last year.

“The problem with Brâncuși is that so few of his pieces come on the market,” Asher said. “There are so few sales at any given time to track where the market is.”

‘Falling in love with statues’

Pivar says his Brâncuși bust came from the collection of Constantine Antonovici, the sculptor’s assistant.

But when asked in an interview to share paperwork establishing its provenance, authentication, or appraisal, the collector said McFadden took all of those documents to facilitate the proposed sale and has not returned them.

Pivar also admits he has nothing on paper memorializing their alleged agreement or even the $100,000 transfer that he claims McFadden suggested. The attorney, he says, kept the only copy.

“You don’t argue with your lawyer,” Pivar said. “And when your lawyer says, ‘Sign here,’ what do you do?”

Asked to explain why he agreed to let McFadden make the sale in his name in the first place, Pivar cited tax advantages and privacy — and then added that traditional auction houses like Christie’s and Sotheby’s no longer accept consignments from him due to “things that have happened in the past that came up with my collection.”

He refused to elaborate, saying he did not believe that to be relevant to his suit. Both auction houses declined to comment, as did the Art Museum.

But despite those potential pitfalls, Pivar remains confident that he will prevail in his case. In telling the tale to a reporter last week, he likened McFadden’s interest in Mademoiselle Pogany to the classic Greek myth of Pygmalion, a story of a sculptor who became romantically enamored with one of his works.

“There’s a history of falling in love with statues,” he said. “[McFadden] fell in love with the [Brâncuși] as soon as he got it in his arms.”

McFadden, meanwhile, appears to be saving his barbs for court.