Jersey Kebab owner sought a better life for his children in the U.S. Now he and his wife face deportation.

The scholar, teacher and restaurant owner sat down with The Inquirer to talk about his faith and journey to America.

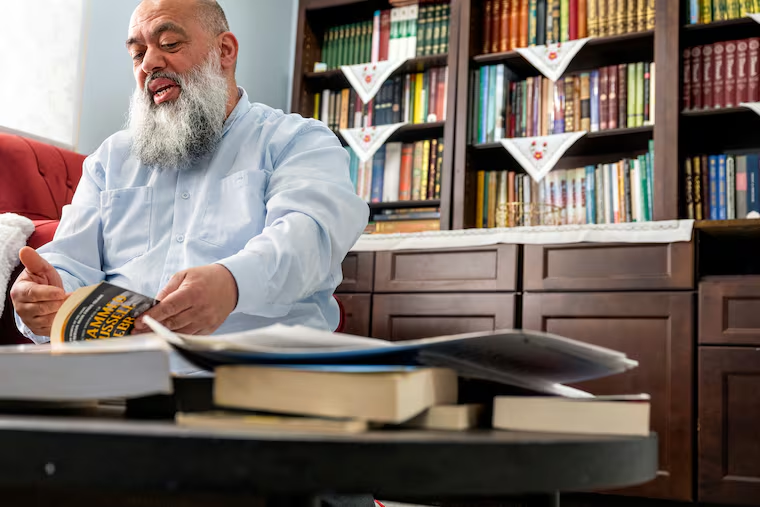

Celal Emanet is sharing some of the books and articles he has written on Islam, scholarship undertaken in three languages, when the ICE monitor on his ankle interrupts, its flat metallic voice bleating that its battery is full.

People who know Emanet say he belongs at a university, teaching in a classroom, not cooking behind a grill at the family’s Jersey Kebab restaurant, and certainly not in the deportation proceedings that the federal government has brought against him and his wife.

“In the beginning,” Emanet said, seated in the living room of his family’s Cherry Hill home, “my heart was full of sadness. But later on, I focus on, ‘This is from God.’ God knows best. And I know God is mercy.”

He was born in Çorum, Turkey, an inland Black Sea-region city known for its archaeological sites and roasted-chickpea snacks, where his family has lived for generations. The study of Islam has been central to his life since boyhood, helping propel him to research in the United States, and to a teaching position at the Bridgeton Islamic Center in Bridgeton, N.J., now part of the Garden State Islamic Center in Vineland.

It also helped bring him to a country where he, his wife, and their two adult children have no official permission to live; the couple’s two younger kids are American citizens by birth.

Until last month Emanet and his family were mostly known only to their customers, to those who frequented the popular Haddon Township restaurant defined by its corner setting and big windows — now covered in paper hearts posted by friends and neighbors. On Feb. 25 they made national news, cited by immigration advocates as a prime example of government injustice after ICE agents appeared at the restaurant and arrested Emanet and his wife, Emine Emanet, 47.

She spent two weeks and a day in ICE detention before being released on bond, as supporters here and elsewhere raised more than $327,000 for the family.

Emanet said before the start of a lengthy interview with The Inquirer that he could not discuss the details of the immigration case.

He was willing, though, to talk about his life and work, his scholarship, and the deep interest and faith in Islam that took him to the United States three times in the years before the family opened the Haddon Avenue restaurant.

At 52, he is the author of 10 books and an expert on Alexander Russell Webb, the 1880s American consul to the Philippines who left his Presbyterian faith to become one of the first prominent white converts to Islam.

It was Emanet’s study of Webb, a journalist and newspaper owner who founded a mosque on Broadway in New York City, that helped bring him to the region. But he is also conversant on the lives of better-known Muslims, including Malcolm X and Yusuf Islam, previously the singer-songwriter Cat Stevens.

Why, some have asked, would a religious scholar open a kebab restaurant?

It’s no mystery, Emanet says. He needs a job to support his family.

He most recently entered the U.S. on an R-1 visa, the type of permission granted to religious leaders. When that visa expired in 2013, he could no longer work for the Islamic Center, he said.

He got a job delivering bread, making daily drop-offs to South Jersey diners. That business suffered when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and diners bought fewer supplies. Emanet needed another way forward, and turned to a business he knew well.

His grandparents ran a restaurant in Turkey. So did his father — several restaurants, in fact. His eldest brother ran a restaurant, as did an uncle and a cousin. He found the Haddon Avenue location in 2020 and opened in March 2021. And he has kept one of his bread routes, to bring in extra money.

Jersey Kebab has been closed since the arrests, but Emanet and his family plan a big reopening on March 30, a community party to coincide with the end of the Ramadan holy month.

Today the family stands among roughly 386,000 Turkish immigrants and people of Turkish ancestry who live in the United States, according to Inquirer computations of U.S. Census figures. That includes about 15,000 in Philadelphia and its suburban Pennsylvania and New Jersey counties.

About 2,000 immigrants from Turkey live in Burlington County, where many run businesses in Cinnaminson and the city of Burlington. Fewer than 1,000 in Camden County, home to Haddon Township, immigrated from Turkey, a longtime ally of the United States, where President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has asserted his hold on society.

Repressive human rights conditions are driving an exodus, and U.S. apprehensions of Turkish nationals at the Mexican and Canadian borders have surged, from a mere 67 people in 2020 to more than 15,000 in 2022 and another 15,000-plus in 2023, dropping to 10,500 in 2024.

Emanet and his family arrived long before that wave.

He cited two main reasons for wanting to live in the United States. First, a better life for his children. And, second, a chance to pursue his scholarship in a diverse environment.

“I picked the United States because I like to see different people,” he said. “Different understandings, different religions, different cultures.”

In high school he considered becoming a journalist, because it guaranteed interactions with others, but in the end, as the child of a devout family, religious study held sway.

Emanet graduated from Ondokuz Mayis University Faculty of Theology in Samsun, Turkey, in 1999, according to his biography. The next year he traveled to the United States on a student visa, seeking to further his studies and learn English, including taking ESL classes at Temple University.

He returned to Turkey in 2003, working on the master’s degree he would receive two years later from the Ondokuz Mayis University Institute of Social Sciences.

At the end of 2004 he came back to the United States on a tourist visa, conducting further research and talking to the Islamic Center leadership about a future job. The next year he began doctoral studies — completed in 2011 — in the Department of Islamic History at Marmara University Faculty of Theology in Istanbul, according to his biography.

His family in Turkey did not want him to go to the United States, he said. To them it seemed unnecessary.

“But I like to pursue knowledge,” Emanet said. “I like to see new people. … God created us in different nationalities, different identities, different colors, different religions.”

In 2008 he arrived in the U.S. with his wife and two children, Mohammed and Zeynep, focused on an intense three-year period of scholarship on Webb, the subject of his doctoral dissertation, and working as a religious leader at the Islamic Center. He and his family have been awaiting a government decision on their application for legal permanent residency since 2016, having been turned down several times previously.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement issued a statement last month saying the couple were illegally in the U.S. and had been placed in deportation proceedings, but has since declined to comment.

Emanet said he always seeks to be an educator, not just at mosques or in newspaper articles or on YouTube, but also in casual places. That includes his restaurant, where a customer recently struck up a conversation about the life of Muhammad.

If his family is permitted to stay, he said, he would like to teach, maybe professionally but at least as a volunteer. While at the Islamic Center, he said, he counseled Muslim inmates at South Woods State Prison in Bridgeton. He can see himself fulfilling that role not just at jails but also at hospitals or colleges.

He doesn’t know if he will get the chance. But he believes from his religious teachings that the outcome has been determined.

“When God creates our soul, our destiny, our fate is written already,” he said. “Our faith is like that. I believe in that. Whatever has been written, it’s going to happen.”

Graphics editor John Duchneskie contributed to this article.