Here are the objections cited in 61 challenges to Central Bucks’ library books

In addition to sex, drug and alcohol use, “inflammatory racial commentary,” gender identity and abortion are all flagged in 61 challenges filed with the school district.

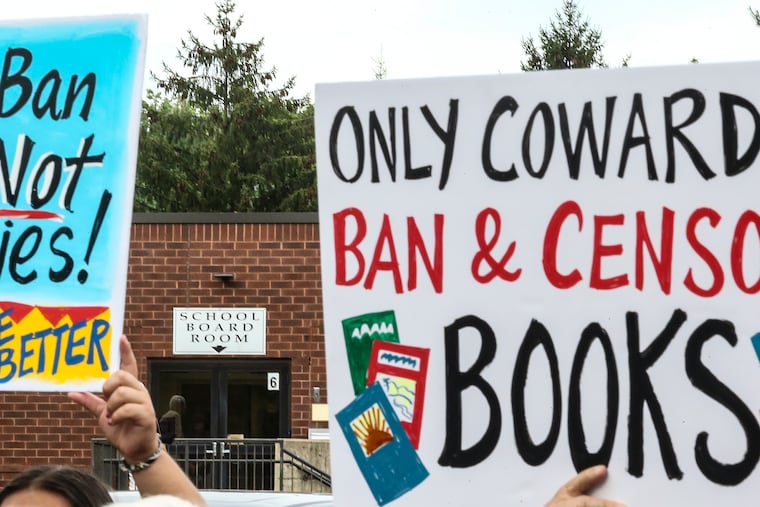

The Central Bucks School District has faced controversy for its policy targeting “sexualized content” in library books. But people who have filed challenges aren’t just concerned with sex.

Drug and alcohol use, “inflammatory racial commentary,” gender identity and abortion are all flagged in 61 challenges filed with the school district, according to records provided by the district.

It’s unclear who filed the challenges, filed over the span of a single week in February. The district — which provided copies in response to a Right to Know request from The Inquirer — redacted the names of the people who submitted them, citing privacy concerns.

A district spokesperson didn’t respond to questions this week about the status of the challenged books. Here’s what the records show about the push to remove them.

Many challenges cite BookLooks

The challenges appear to draw heavily from a website that has been linked with the Moms for Liberty group called BookLooks, which catalogs “objectionable material” and assigns books ratings.

The site describes itself as run by parents in Brevard County, Fla., where Moms for Liberty began. While BookLooks says it isn’t affiliated with any other group, the Moms for Liberty chapter in Brevard County has said its book review committee created the same rating system used on BookLooks.

The challenges filed with Central Bucks list passages that appear verbatim on BookLooks, and use the same “profanity counts” tallying the number of times various words appear throughout the books.

In numerous cases, the challenges provide links to reviews on BookLooks.

“I do not need to read the book because the above website already outlines all issues,” one person wrote in challenging The 57 Bus, by Dashka Slater, an award-winning nonfiction book about a transgender teen set on fire by another teen on a bus in Oakland, Calif. (For 40 of the 61 books being challenged, people said they hadn’t actually read the books.)

Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, said that although BookLooks launched last year, “multiple resources have been in use for decades,” crafted by education and child development professionals, to help guide librarians’ book selections.

“No one source should be the one determinant of whether a book is part of a library’s collection,” said Caldwell-Stone, whose organization has tracked a rise in book-banning demands driven by organized groups.

Sexual scenes ‘give students ideas’

Those challenging books primarily quoted graphic sexual scenes — listed off by page numbers — and said they didn’t see the value to students.

“This is a disgusting and inappropriate book,” one person wrote of Living Dead Girl, by Elizabeth Scott, a novel about a girl kidnapped by a pedophile, in response to a question on the challenge form asking how students would be negatively affected by the book. “It gives the student ideas of sexual depravity and child abuse beyond the scope of everyday life.”

Planting ideas in students’ heads and “normalizing” aberrant behavior were listed as concerns throughout.

“Degrading sexual acts to casual actions could negatively affect a child’s view of what a normal act between two married people should be,” someone wrote of The Haters, by Jesse Andrews, a coming-of-age book about aspiring musicians who flee their summer camp and take a road trip.

“I feel the material in this book is completely inappropriate for minors,” one person wrote of L8R, G8R, by Lauren Myracle, a book written in the form of instant messages between three girls. “Group sex, dominatrix, illegal drug use including Vicodin with a RAGING drug epidemic in this country? This is not OK.”

People also argued against any depictions of sexual assault. “Rape is not an appropriate subject for minors,” someone wrote of All the Things We Do in the Dark, by Saundra Mitchell, a thriller about a young sexual assault survivor.

“The book has ideas of feminist ideologies and activism, rape scenes, and violence,” one person wrote of Shout, by Laurie Halse Anderson, a memoir about the author’s experience being raped at 13. “Students may be desensitized to the disturbing crime of rape, and not even recognize if it were to happen to a friend or themselves.”

Anderson, who lives in Upper Dublin and last month won the world’s largest prize for children’s literature, told the Central Bucks school board last month that banning her book, and others detailing abuse, would be “educational malpractice.”

“Bad things happen to our kids much more than any of us want to admit,” Anderson said, describing books as a way to allow children to see their experiences reflected and to spur needed conversation.

But it’s not just about sex

While proponents of Central Bucks’ book policy have said their focus is on sexually explicit content, those challenging books have other objections, as well.

Numerous books that discuss racism — such as Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye — are cited as having “inflammatory” or “controversial” racial commentary, among other concerns.

The challenge filed to Tiffany D. Jackson’s Monday’s Not Coming included this quote: “Later on, developers realized how valuable the land was, sitting right on the river, with easy access to the city. Too valuable for black folks to have. How convenient that crack would ravage the area developers wanted most.”

Several challenges included objections to the topic of abortion.

“Abortion is depicted at the end of the book. It is presented as an option. This is disturbing. Some student’s religion do not subscribe to abortion,” wrote the challenger to Girl in Translation, by Jean Kwok. (Kwok is expected to travel to speak at a Central Bucks school board meeting Tuesday, according to the Bucks County Courier Times.)

Regarding Flamer, by Mike Curato, a graphic novel about a Catholic boy coming to terms with being gay, a challenger wrote: “Another book putting down an organization based on nationalism, the Boy Scouts.” (The person also noted “repeated discussions of a 14-year-old boys introduction to porn, masturbation, and sexy dreams. Really not things I want to be thinking about.”)

Central Bucks, which has been facing a U.S. Department of Education investigation over allegations that it created a hostile environment for LGBTQ students, says its library policy doesn’t target LGBTQ-themed books. But numerous challenges cite “alternate sexualities” and “alternate gender ideologies” as warranting removal.

“There are two genders thus CBSD is providing inaccurate biological information and suggestion on medical procedures for minors,” someone wrote of Lily and Dunkin, by Donna Gephart, a story about a transgender girl and a boy with bipolar disorder.

“Why is our school providing books that will have elementary aged children entertain the idea that one can just pick to be a different gender and it is OK?” a challenger wrote of Melissa, by Alex Gino, about a transgender child.

Before receiving any formal challenges, district administrators earlier this year disclosed that they were already reviewing five books for possible removal in order to “guard against the sexualization of children.” Of those five books — This Book Is Gay; Me and Earl and the Dying Girl; Gender Queer; Lawn Boy; and Beyond Magenta — four center on LGBTQ characters.

The voices of LGBTQ people and people of color are “disproportionately represented” in recent book challenges nationally, Caldwell-Stone said.

“That’s the sleight of hand: Books that represent the lives and experiences of LGBTQ persons are made to fit under the definition of sexual content,” she said.