An app wants to give Philly residents real-time alerts on crimes happening nearby. Is that a good thing?

Philadelphia is the Citizen app's fifth market, joining New York, San Francisco, Baltimore, and Los Angeles. But it's not clear it will receive a warm reception in the city of Brotherly Love.

When it launched in New York three years ago, the smartphone app called “Vigilante” quickly sparked controversy. Its creators lauded it as a way for users to get and receive real-time notifications about crimes in their neighborhood.

Critics were wary, not just about the aggressive-sounding name but aspects like its “report incident" feature that encouraged users to alert authorities to crimes in progress and a “record” button enabling them to upload photos or videos. The New York Police Department panned it, issuing a statement pointing out that “crimes in progress should be handled by the NYPD and not a vigilante with a cellphone.”

Apple removed it from its app store.

So its creators rebranded it in 2017 — as “Citizen” — and tried again. And now it’s come to Philadelphia.

Citizen sends users real-time alerts intended to keep “everyday people informed with real-time notifications about nearby crime, emergencies, and ongoing incidents," according to J. Peter Donald, a former high-ranking NYPD officer who now serves as Citizen’s director of policy and communications.

He acknowledged the early struggles but said: “Now we have a new name and a new mission.”

Philadelphia is the company’s fifth market, joining New York, San Francisco, Baltimore, and Los Angeles. It claims to have more than 600,000 users.

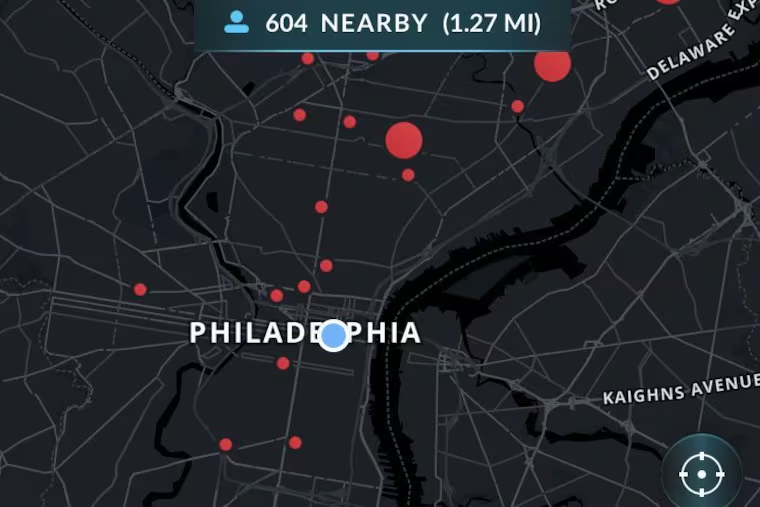

Here’s how it works: A group of 50 employees — including former journalists, former first responders, and an ex-English professor — monitors 911 calls and dispatcher responses, mainly public-safety issues, and translates them in real time for its users. They send out about two million notifications per day across the five cities. Each alert is marked with a corresponding dot tacked onto a localized map.

The company says it instructs its app users to avoid these marked areas, but the app also includes a “Record” button, which would enable users to upload a live video or photos of an active crime scene. It says users have uploaded more than 100,000 videos, which the company won’t sell but has shared with news organizations.

Donald said the company has reached out to the Philadelphia Police Department, as well as local anti-crime groups and neighborhood watchers, but has not heard back from Commissioner Richard Ross. (The Inquirer also reached out to the Police Department for comment but messages were not returned.)

Despite the rebranding, it’s not clear that Citizen will receive a warm reception in the City of Brotherly Love. John McNesby, president of Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 5, the officers union, wasn’t convinced of the app’s usefulness.

“We have one already, it’s called the 911 app,” he said. “We got a police department that is very good at what they do, and for people to get into taking matters into their own hands, that could be a disaster. Somebody is trying to make money off people getting hurt and people being victimized, and it’s crazy."

Hans Menos, executive director of the Police Advisory Commission, cited issues that have cropped up with other apps such as Nextdoor, the neighborhood-focused gossip forum, which encountered blowback when messages were labeled as racist.

“One of the things that concerns me about these citizen-involved apps or platforms is they have a high potential for misuse,” he said. “But, in general, I like the idea that people can be more aware of what’s going on in their neighborhood.”

In San Francisco, where the app debuted in fall 2017, the reviews have been mixed.

Users have reported issues with its sources of information. The app developers do not have access to the 911 radio channel, but rather monitor scanner chatter. And the chatter is based on civilians who call 911 and their initial reactions to incidents, which are subject to interpretation.

But there have not been any reports of overeager app enthusiasts intervening in crimes in progress.

Sgt. Michael Andraychak, spokesperson for the San Francisco Police Department, said police officials met with representatives of the app in 2017, but the department is not “directly involved with the App or its developers.” Officers don’t need the video; they already have their own body cams, he noted.

“We are still evaluating the pros and cons of the product,” Andraychak said, “but it doesn’t factor into our day-to-day operations.”