How a Philly teen is changing the lives of thousands of Liberians

“When I heard Destinee’s story, I cried,” Sackor said. “I was really surprised, and I was touched that a girl of her age would think about other people’s lives that way. When I think of it, I say, ‘Oh my God, this is unbelievable.'"

Destinee Whitaker was in fourth grade when she first became aware that millions of people in some parts of the world lacked clean water.

“It was a problem that just stuck with me, that not everyone had what I had, that not everyone lived the way that I live," said Whitaker, who grew up in West Philadelphia. “Water is a necessity.”

When she got to Carver High School of Engineering and Science, a Philadelphia magnet school, Whitaker researched the issue carefully. And then she felt compelled to do something.

Early in her senior year, Whitaker approached fellow members of the school’s National Honor Society with a proposal: They should raise money to buy water purification systems for people in need. Whitaker, the National Honor Society president, knew the systems would have to be portable and able to operate without electricity. So she checked with a microbiologist to make sure the system she had her eye on would fit the bill.

Once her classmates agreed to back the proposal, Whitaker took it upon herself to dream up ways to raise money. She organized bake sales, dress-down days, and a game where students purchased tickets to guess how many pieces of candy a jar contained.

“It was all about networking,” said Whitaker, who attended Overbrook Elementary and Masterman for middle school. “I’m a well-rounded person; I know a lot of people at school. I spread the word to them, and they spread the word to their friends.”

Already important to her, the cause soon because a mission, Whitaker said. And yes, she said, taking on the project while handling regular schoolwork and college applications was slightly intimidating.

» READ MORE: Not everyone can get to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. So the Wall comes to them.

Ted Domers, Carver’s principal, watched as Whitaker blossomed into “such a servant-leader” with the project. “It was the first time our National Honor Society had a focus like this, and she became an expert,” he said.

Whitaker and her classmates raised $800, a significant amount in a school where 70% of students’ families are considered economically disadvantaged.

Raising the money turned out to be the easier part of the endeavor, said Whitaker, now a freshman environmental sciences major at Spelman College in Atlanta. Finding an organization that could promise to deliver the water purification systems was the bigger puzzle.

With the help of Carver staff, Whitaker reached out to churches and mission groups, college professors and others about their possible connections to projects in Africa, Central and South America. No one could help.

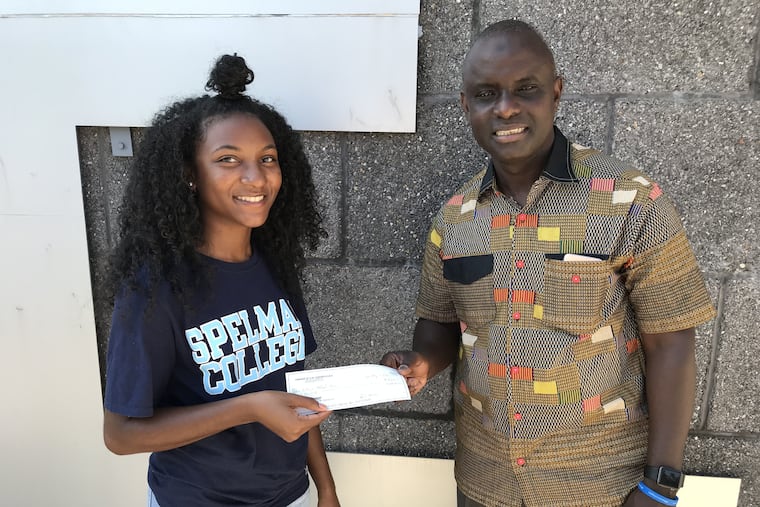

Then Whitaker connected with Joseph Sackor, who runs the Liberia Medical Mission, a nonprofit that provides medical services to Liberians who lack adequate health services. Sackor, who lives in Bucks County and works in Philadelphia, was astonished to hear about Whitaker and her efforts to help strangers living thousands of miles away.

Sackor has accepted the funds, and agreed to deliver the systems to people who need them.

“When I heard Destinee’s story, I cried,” Sackor said. “I was really surprised, and I was touched that a girl of her age would think about other people’s lives that way. When I think of it, I say, ‘Oh my God, this is unbelievable.' "

Sackor, a Liberian native who fled the country when war broke out, said the purification systems will make an immediate difference in the lives of “thousands and thousands” of people in a country where diarrhea from dirty water is a major cause of death in young children.

» READ MORE: Teen creates superhero with Tourette syndrome to help young people embrace their differences

He has identified a medical clinic and a school where the systems will be life-changing.

“Some students actually stay away from school because their parents cannot afford to buy them bottled water,” Sackor said. “This is huge.”

Eventually, Whitaker dreams of launching her own nonprofit to bring clean water to places that need it. But for now, she’s thrilled to work with Sackor, and is looking forward to finding more ways to collaborate.

Domers doesn’t doubt that Whitaker will continue to make change.

“The kid’s going to be a superstar," he said.