Philly social media influencer ‘Meatball’ charged with six felonies after digital cat-and-mouse game with police during looting

Police allege Dayjia Blackwell went to seven locations where property destruction and burglary took place as part of looting across Philly Tuesday night that was partly organized on social media.

The vandalism and theft that spread across Philadelphia on Tuesday night were at least partially organized on social media, according to police, and some of it was also broadcast live on Instagram and TikTok by a 21-year-old social media influencer from North Philly known as “Meatball.”

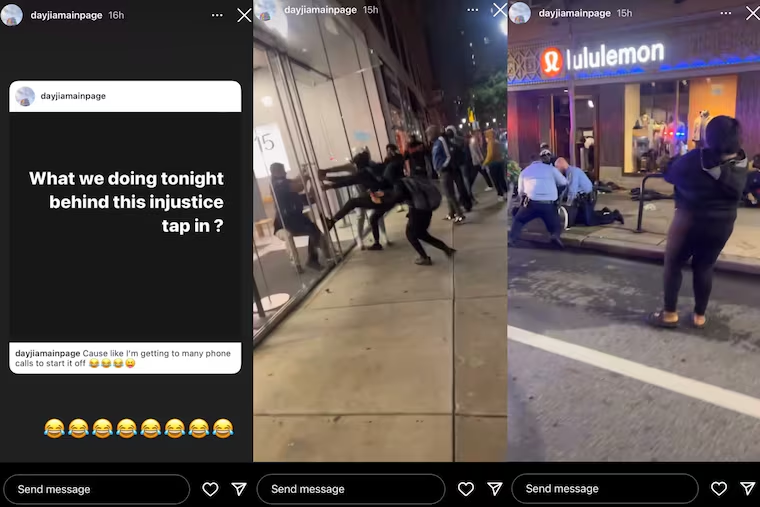

“What we doing tonight behind this injustice tap in?” Dayjia Blackwell wrote to her roughly 185,000 Instagram followers, referring to a judge’s decision earlier in the day to drop all charges against former Philadelphia Police Officer Mark Dial, who was arrested in the fatal shooting last month of Eddie Irizarry, 27, during a traffic stop.

Interim Police Commissioner John Stanford has described the thieves as “opportunists” who piggybacked on the anger and grief surrounding the Irizarry case.

After a peaceful downtown protest disbanded about 7:30 p.m., Blackwell, who also has 466,000 followers and 13.4 million views on TikTok, was already in Center City surrounded by a group of other young people that seemed to grow by the minute.

“What store we going at first, y’all?” she said to the camera.

Someone replied: “Apple Store.”

Vandals later hit the Apple Store location on Walnut Street — along with a nearby Foot Locker and Lululemon. In the ensuing hours, more thieves on foot or in cars would descend upon the Roosevelt Mall in Northeast Philadelphia, stores along Aramingo Avenue, and elsewhere. The Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board temporarily shuttered retail locations in Philadelphia after 18 state-run liquor stores across the city were broken into overnight.

Stanford said officers were already downtown due to the Irizarry protest, so they were able to quickly respond to the initial looting reports in the Rittenhouse Square area. But cops were also monitoring social media to respond to the reports citywide, in what has become something of a familiar cat-and-mouse game around the country.

“We were able to link some things on social media,” Stanford said at a news conference held late Tuesday night. “We had a group that was making their way through the city. Quite naturally, you have followers who are going to see this and start to come out, and think they have an opportunity to get something.”

But while videos of posh stores being broken into went viral and attracted international news coverage, this pattern is not exactly new.

In 2010 and 2011, several similar episodes downtown — described by the media at the time as “flash mobs” — saw downtown department stores similarly swarmed by crowds of upward of 100 teens. Police later traced the origins of one such act back to private messages on the social networking service MySpace.

In a 2011 Department of Justice report on the rise of social media-related crime across the United States, then-Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey stated that the department had been caught off-guard by these episodes, some of which were organized days in advance, because authorities were “not routinely viewing social media sites.”

That quickly changed, according to Ramsey. In 2013, police issued a formal directive stating that the Police Department’s Criminal Intelligence Unit would be assigned to conduct “covert intelligence gathering efforts” using “social networks or computer programs” at the request of police commanders. Police also began coordinating with the economic development agency Center City District to disseminate information about potential acts to merchants.

The difference between today and a decade ago is the increased popularity of social media and the speed with which information can spread using modern apps.

“As use of social media has expanded generally, so, too, has police use of social media,” said Rachel Levinson-Waldman, an expert on police surveillance at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York.

Although a Philadelphia police spokesperson did not respond to questions about the exact nature of their efforts, Levinson-Waldman said some law enforcement officers now use undercover accounts, as well as software that allows them to sift through large amounts of data, such as locations, names, and hashtags.

“It really does supercharge police capabilities,” said Levinson-Waldman, who has also raised privacy concerns around such high-tech surveillance initiatives.

While the downtown “flash mobs” were largely contained to a small geographic area, the vandals and thieves on Tuesday moved relatively quickly through Center City, West Philly, and Northeast Philly, directed in part, it seems, by livestreaming and other social media chatter. (A series of recurring illegal car rallies on city streets has employed similar tactics, with meet-up locations disseminated through private messages to evade police rapid response units.)

“OK, where we going next? Where we going next?” Blackwell shouted on camera after the crowd left the Apple Store with arms full of iPhones and iPads. She pointed her camera at the Lululemon store as they ran in that direction.

On Tuesday, some appeared to expect a repeat of the mass demonstrations that followed the 2020 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, and strained police responses to criminal activity. This time, that didn’t materialize.

Blackwell was arrested mid-livestream, one of the 52 people taken into custody Tuesday night. She was charged Wednesday evening with six felonies and two misdemeanors, including burglary, conspiracy, riot, and criminal use of a communication facility.

Police allege that Blackwell went to seven locations where property destruction and burglary took place. But her arrest could raise a chicken-and-egg legal question: Was she livestreaming crimes in progress? Or were the crimes facilitated by her livestreams?

“If she was taking part in it or saying, ‘All right, come to this next location armed with rocks because we’re going to break windows,’ that seems like one thing — vs. basically documenting it,” said Levinson-Waldman, a former trial attorney in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. “Even if she has some information about where people are going next, I don’t really understand how that’s different from journalists’ work, or being a citizen journalist.”

Police declined to comment on her arrest.

On Wednesday, a woman who said she was Blackwell’s mother went on Instagram herself to discuss the situation. She used the opportunity to promote the hats that Blackwell sells on her page.

“Going to get my kid,” she posted on her Instagram story, followed by: “Beanies for sale $50. Free meatball.”

Staff writer Ellie Rushing contributed to this article.