Daylight saving time has begun. Most people just want to stop changing their clocks.

The clock change remains a "hot issue" nationally, with 32 legislatures considering bills to change the system.

One of America’s most contentious hours officially doesn’t exist.

On the issue of daylight saving time, which began officially at 2 a.m. Sunday — or was that 3 a.m.? — America is a nation divided. Either way, the citizenry loses a precious weekend hour; in exchange, millions more folks get to eat their dinners before dark.

According to the National Conference of State Legislators, lawmakers in 32 states are considering bills that would change the current system of splitting the year into about eight months of daylight time and the rest, standard.

“It’s been a hot issue,” said Jim Reed, an NCSL official. And it’s getting hotter, he added. Every year more state lawmakers are considering changing the system. The preponderance are pushing for year-round daylight time, although Congress has forbidden states from doing so.

Pennsylvania has four different proposed time-change bills, and three of those essentially endorse year-round daylight time.

Yet, if the issue were put to a national primary, all-standard, all-the-time would win decisively, according to a poll conducted last year. More than 70% of those surveyed said, Please, stop with the changes, period.

The nation did try year-round daylight time back in 1974, during an energy crisis brought on by an oil shortage. It was not well-received. It went into effect on Jan. 3, and a whole lot of folks didn’t like the idea of the sun rising over what used to be their coffee-break time.

By the end of the month, the national school boards association called for an immediate cease-and-desist order because school buses were ferrying kids in the dark. Florida state officials blamed morning darkness for eight deaths.

On Sept. 30, Congress decreed an end, and the clocks went back on Oct. 27, 1974.

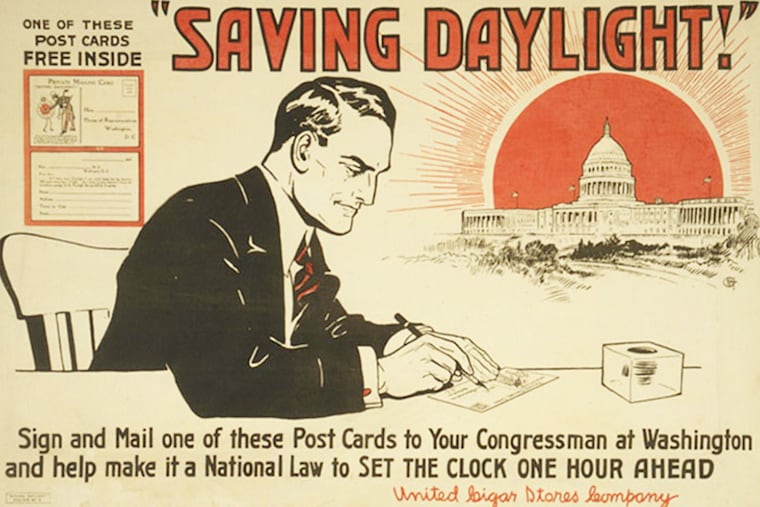

According to the Congressional Research Service, DST began in Germany on May 1, 1916, as a war-conservation measure. The idea caught on across the continent and eventually landed in the United States in 1918.

The first DST clock move-up didn’t go over well. It occurred March 31, which happened to be Easter. Clergy and church-goers were not pleased at how this affected sunrise services. Congress eventually abolished the plan, but reinstated it for good (depending on one’s perspective) in 1966. But not everyone cooperates: The clocks don’t change in Arizona or Hawaii, which is about halfway to tomorrow from the Eastern Time Zone.

Through the years, DST has encroached on standard time, which is by no means the standard anymore.

It’s in effect only about four months a year, including day-challenged February. Daylight saving time now constitutes two-thirds of the year.

DST critics have pointed to studies pointing to possible connections to an increase in heart disease when the clocks go up, and the impacts of disrupted body rhythms resulting from disrupted sleep patterns.

Proponents say later sunsets mean more Vitamin D and more opportunities to luxuriate in the later twilights.

All that said, we are confident that the clock change will not be particularly popular on Monday morning.