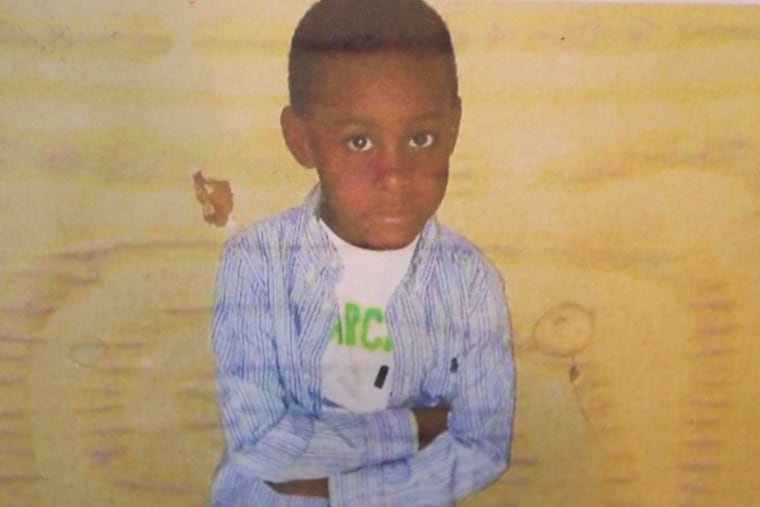

Father and another man charged in 7-year-old boy’s 2018 subway death

The death is also prompting safety changes on SEPTA's subway cars.

This story has been updated.

The father of a boy killed on the Broad Street Line last year has been charged with involuntary manslaughter and conspiracy in the 7-year-old’s death.

Aden Devlin was walking between two subway cars, selling candy, when he fell and was run over near the Allegheny station on Sept. 23, 2018.

Aden’s father, Troy Devlin, 37, of Philadelphia, faces charges of endangering the welfare of children, corruption of minors, and reckless endangerment of another person. He was arrested Saturday and was held on $200,000 bail.

Another man, Jahras Edwards, 27, was with Aden when he died and is expected to be charged with murder, conspiracy, endangering the welfare of children, corruption of minors, and reckless endangerment of another person, according to the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office.

Edwards remains at large, and authorities are urging him to turn himself in.

The charges for both men were reviewed by the District Attorney’s Office and filed by SEPTA Transit Police.

The two men were using Devlin’s children and others from their Strawberry Mansion neighborhood to earn money for them, the office reported. Edwards was earning $300 a day through the children’s work, said Roh.

“That is child labor,” she said. “Last I checked, child labor is illegal.”

In a 2018 interview with The Inquirer, Aden’s family said Aden was selling candy on the train with his 11-year-old brother and Edwards, described as a family friend. Aden had sold candy at the 69th Street Transportation Center since he was 4, his family said, and had begun selling on the train a year before his death.

On the day of his death, Aden and the two others were traveling between cars before the train left the North Philadelphia stop, but Aden dropped candy as the train began moving. He tried to get the candy, but slipped. His brother tried to catch him, family said, and Edwards then grabbed the 11-year-old, but Aden fell between the moving cars onto the tracks.

Aden’s family could not be reached for comment Thursday night.

Nine people died on SEPTA’s two subway lines last year, according to a federal database. Two of those were passengers, and three were recorded as suicides.

Aden’s father said in the 2018 interview that teaching his sons to sell candy showed them “how to make money without doing illegal stuff, at a young age.”

But selling anything on the train is illegal, SEPTA officials said.

Sales and busking are a constant, nevertheless, ranging from teenagers doing acrobatic dance moves on a moving train to a person selling water or deodorant.

“They’re not allowed to do that,” said Andrew Busch, SEPTA spokesperson. “Any time police become aware of it, they respond to it. I don’t know if there’s necessarily a way to step up enforcement of it.”

» READ MORE: 7-year-old who died after fall from SEPTA train remembered for entrepreneurial spirit

Along with the charges, the National Transportation Safety Board released Thursday its recommendations following a nearly yearlong investigation.

SEPTA’s subway cars have little protection for people walking between them, merely an extension of the walkway from the ends of each car, and six chains alongside the narrow pathway. Riders are not supposed to travel between trains while the vehicles are in motion. At the time of the boy’s death, SEPTA’s warnings on the doors, “No Passing Through,” were vague and weren’t designed in a way to ensure they would grab riders’ attention.

The next day, the NTSB reported, SEPTA installed new signs that were more eye-catching and told riders, “Keep Door Closed” and “Do Not Move Between Cars."

The NTSB acknowledged in its report that better signs don’t eliminate the danger inherent in an open walkway between subway cars. Redesigning the subway fleet with an enclosed pass-through isn’t practical, though. The federal agency noted other rail agencies had addressed the danger by adding door handles encased in protective covers that warn they should be used only in an emergency or, in the case of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, that are unlocked only when there is an emergency.

» READ MORE: SEPTA’s safety rules should prevent subway deaths, but on Monday, something went awry

Starting this fall, Busch said, SEPTA will begin a pilot program on the Broad Street and the Market-Frankford lines that emulates the Boston system.

“The doors would lock unless there’s an emergency,” he said, “and there would be instructions on how to open it in case of an emergency.”

The NTSB also found there was no unified system of notification on U.S. subways to warn people about the dangers of passing between cars. The board recommended the Federal Transit Administration design a uniform notification system and require subway operators to install those signs.

:Staff writer Robert Moran contributed to this article.

CORRECTION: On Thursday evening, the District Attorney’s office provided incorrect information about the status of Jahras Edwards. He remains at large.