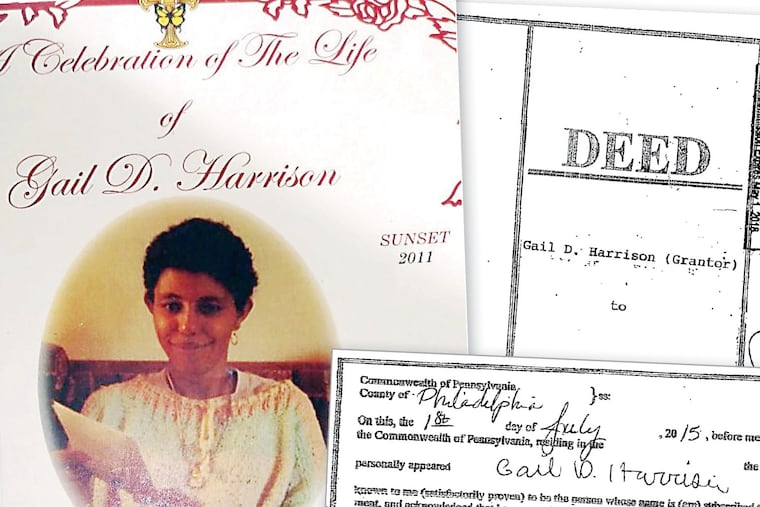

With questionable signatures and a dubious will, a man lays claim to a dead woman’s house

Questions have been raised over the efforts to acquire a rowhome in a gentrifying Philadelphia neighborhood.

To hear Donnie McLaurin Jr. tell it, the story is almost magical.

He says Gail Harrison, childless and unmarried, befriended him while he was growing up in Brewerytown. She took him in while his dad was in prison. She was like his stepmother. He called her “Mom.”

True, he missed her funeral, but he felt close enough to rummage through her house uninvited after she died in 2011. There, he says, he found something amazing.

“I ended up coming across this paperwork and the will,” he said.

Dated when McLaurin was just 14, the will named him her heir, putting him in line to inherit her newly valuable home in a quickly gentrifying North Philadelphia neighborhood.

Neighbors and friends of Harrison have another word for McLaurin’s story. They say it’s fiction.

They scoff at the idea that Harrison, a recluse struggling with mental illness, had any relationship with Donnie McLaurin. They say they called the police when, after Harrison’s death, they saw McLaurin crawl through a window and take bag after bag of belongings out of her house. His father, Donnie McLaurin Sr., was there too, in their telling. And they say the father yelled to his son at one point: “You find the money yet?”

As for the will, McLaurin Jr. filed it with the city four years after Harrison’s death. Harrison’s signature appears forged, according to a handwriting expert. So does the signature of the will’s notary. The notary’s stamp appears fake as well. It bears a date when the notary wasn’t in business.

Philadelphia Register of Wills Ronald Donatucci’s office in 2017 accepted McLaurin’s claim as Harrison’s heir. Upon review, Donatucci now says, the will appears to be a counterfeit.

Harrison died alone at age 59 of heat stress during a heat wave. Her obituary, written by her family, makes no mention of McLaurin Jr., citing only her brother, his wife, and their son, Devin. Neighbors said Harrison was close to Devin and talked of leaving her house to him.

The Tangled Timeline of Gail Harrison's Home

In life, Gail Harrison attracted little attention. In death, her house became a magnet for thievery and suspicious dealings.

In a recent phone interview, McLaurin Jr., now 28, told of discovering the will and of his friendship with Harrison. Pressed by a reporter, he eventually hung up. His criminal defense lawyer, Derek Steenson, later backtracked for his client. According to Steenson, McLaurin Jr. told him that in fact, his father and a family friend found the will, and that the friend filled out the paperwork to file it. The friend is now dead, Steenson said.

If the will is bogus, it would suggest that Gail Harrison, in death, was the victim of two separate scams designed to ransack her estate, one involving a forged will and the other turning on a forged deed.

As the Inquirer previously reported, a man named William E. Johnson III ended up the owner of Harrison’s two-story rowhouse on Seybert Street in 2016, five years after her death, courtesy of a deed bearing her forged signature. Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, heralding a crackdown on the entrenched problem of housing theft in the city, announced Johnson’s arrest this month on charges of stealing her home and six others.

In investigating Harrison’s house, the Inquirer found the will that Donnie McLaurin brought to the Register of Wills Office in 2015.

The document is 11 typed pages and dated April 12, 2004. It shows no involvement of a lawyer. It variously describes Donnie McLaurin Jr. as Harrison’s child and her stepson, and names him heir and executor of her estate. The filing lists her house as her only asset.

The will bears the signed names of Gail Harrison and notary Edward R. Gudknecht, who served as Bucks County recorder of deeds for 24 years until his death in 2010. Both signatures appear to differ significantly from other known samples.

The Inquirer asked Joseph Rosowski, a trained forensic documents examiner, to compare the handwriting in the will with Harrison’s and Gudknecht’s signatures on other official documents, such as Harrison’s voting registration. Rosowski is a police detective in Northampton Township, Bucks County, and works on the side as a documents expert. He has testified as an expert in nearly 150 trials.

While saying he would prefer to have more examples for comparison, Rosowski cited numerous discrepancies with the signatures. Gudknecht’s name, for instance, appeared to be misspelled on the will. He said the signatures on the will purporting to be Harrison’s and Gudknecht’s both appeared to be forgeries.

Donatucci, the elected head of Philadelphia’s wills office for nearly 40 years, agreed. “It’s so obvious it’s not the same signature,” he said this week, referring to the signed names of both Harrison and Gudknecht.

Gudknecht’s daughter, Sally Carr, also declared the signature on the will a fraud.

“I know my dad’s signature," she said. "It’s definitely not his signature. There’s no question.”

The notary stamp on the will declares Gudknecht licensed through 2005. In fact, records show that Gudknecht let his license lapse in February 2004.

Donnie McLaurin Jr. is awaiting trial for allegedly raping a woman last year. Steenson, his lawyer, says the woman’s account is false. On his bail papers in October, McLaurin listed Harrison’s house as his address.

In his interview, McLaurin insisted the will was legitimate. In a separate interview, his father did, too. They disagreed about much else.

The son said his father had dated Gail Harrison for a time. “My mom got custody of me while he was locked up,” he said of his father. “Two years, I was like back and forth.”

McLaurin Sr., 52, said he never dated Harrison or served time in prison. “I don’t know what he told you,” the father said of his son. “I was never locked up.”

There are no state or federal records of him being in prison.

As for the son’s living with Harrison, the father said Harrison would help the boy with his homework, but he never stayed with her.

The younger McLaurin acknowledged that about four years after Harrison died, he went into her house to clear it out. He said he had a right to do that. “I knew it was still my mom’s house,” he said.

“We cleaned it out,” he said “I found the will inside this little envelope.”

The son said he and his father had gone through the house together. Not so, his father said: “I wasn’t with him.”

In any event, the will was a big surprise. The McLaurins said Harrison had never told them she had made McLaurin Jr. her heir.

Residents on the block question the McLaurins’ account.

In interviews, three said they watched on a hot day as the McLaurins, father and son, went in and out of Harrison’s house, carting off her possessions.

“They took out, like, appliances. They had stuff in plastic bags,” said Terry Robinson. “They took a lot of stuff out of there. She had stuff still in boxes that had never been used.”

Robinson, 62, and her daughter, Jalena, 26, watched in alarm as the McLaurins and a third man drove up, entered the house though a window, and began passing items out. They included a strongbox for papers.

The McLaurins opened windows to air out the house, they said. While the father was downstairs, Jalena Robinson said, his voice carried across the street as he yelled upstairs to his son, “Don, you find the money yet?” — a statement denied by McLaurin Sr.

Neighbors also rejected the idea that Harrison was a mentor to McLaurin Jr. “She never had people over,” said one resident, who did not want to be named. “I lived on the block for over 55 years. We looked out for her. I don’t even think she knew him.”

Few questions asked

McLaurin brought the will to the Register of Wills Office in City Hall in December 2015. The office approved it 14 months later, in February 2017.

Louis DiRenzo, a deputy register of wills, said a key positive factor was that McLaurin attached the required death certificate, certified by the state as an official copy.

By law, death certificates are not public. They generally may only be obtained by relatives.

In practice, the state will mail them to anyone who claims to be a relative, officials acknowledged. “We don’t have the ability to check,” said Nate Wardle, a spokesperson for the state Department of Health. He said the state relies on the honor system, noting that its form requires people to affirm they are being truthful.

For his part, McLaurin Jr. said of the death certificate, “My mom’s family gave it to me.” He said he couldn’t recall which family member.

Harrison’s brother declined to comment.

DiRenzo said the wills office tries to check submissions. People claiming to be heirs are sometimes asked to produce birth certificates. While he agreed the will submitted by McLaurin raised issues, he said he could not fault the office’s handling of the case.

“Everything on our end looks appropriate,” he said.

At this point, under state law, only Harrison’s brother can contest the will, Donatucci said. He said he planned to alert the District Attorney’s Office to the questions about the will.

“I’m not happy that my hands are tied,” Donatucci said. “I’m sad that the family has to go through this grief.”

From 2015 on, McLaurin appears to have used Harrison’s old address as his own. He gave it in obtaining a driver’s license that year, records show.

A forged deed

While the will McLaurin presented was under review by the Register of Wills Office in 2016, prosecutors allege, Johnson, 43, stole the house out from under him with a forged deed. They said he faked Harrison’s signature and a notary’s to steal the property.

He sold the house for $89,000 to a developer, who renovated it and sold it again for $250,000 to Melvin Powell III and his father. The sale apparently didn’t faze McLaurin Jr., who was still listing the house as his address in October when he was arrested on the rape charges.

Confronted later by a reporter about problems with Harrison’s will, Donnie McLaurin Jr. said he had given up any claim on the house. His father, however, is digging in.

McLaurin Sr. said he had considered suing the Powells, but “I came to the conclusion they are just as much a victim as my son."

Now, he said, he might go after the title company that approved the purchase. He recently left a note at the Powells’ mailbox asking to talk with them.

They say they won’t be responding.