Delbert Africa, MOVE member released from prison in January after 41 years, has died

Africa, 73, died at home in Philadelphia surrounded by family and members of MOVE, Pam Africa, a MOVE member, said Tuesday.

Delbert Africa, a longtime member of MOVE who was released from prison in January after serving 41 years for his part in the group’s 1978 clash in Powelton Village with Philadelphia police, has died.

Africa, 73, died at his home in Philadelphia Monday surrounded by family and fellow MOVE members, Pam Africa, also a MOVE member, said Tuesday.

He died of prostate and bone cancer, said his daughter, Yvonne Orr-El, who was among a handful of speakers at a news conference during which she and others alleged that he did not receive medical treatment in prison for 18 months after first noticing symptoms.

“Had my father received the treatment he needed, the healthy, strong, smiling, humorous, sarcastic man that I called my father would still be here today,” Orr-El, of Chicago, said in front of a MOVE-owned home in the 4500 block of Kingsessing Avenue.

“What happened to Delbert was just another example of George Floyd. Delbert was deliberately, methodically, calculatedly murdered by prison officials,” said MOVE member Janine Africa. “When he came out here to these doctors and hospitals on the streets, they even said that the prisons did a lot of wrong things to Delbert.”

A spokesperson for the state Department of Corrections said she could not discuss a specific inmate’s medical care, but said that in general, “DOC officials provide medical care that is in line with community standards.”

Pam Africa said Delbert Africa would be remembered as “an uncompromising, revolutionary freedom fighter who fought for the lives of all.”

Delbert Africa was one of nine MOVE members imprisoned after the 1978 clash. After being released, he said he looked forward to reuniting with the surviving MOVE members to continue the work of challenging what he called an unjust criminal justice system.

“I want to keep on pushing the whole front of fighting this unjust system. I want to keep on pushing it and do as much as I can in my time here," he said.

MOVE was created in 1972 by West Philadelphia native Vincent Leaphart, who called himself John Africa and preached an ideology centered on black revolutionary ideas and back-to-nature philosophies. The members considered MOVE their religion, adopting anti-technology and anti-government beliefs while taking on issues ranging from police brutality to animal rights.

In 1978, after a year of legal wrangling between MOVE and the city, police raided MOVE’s Powelton Village home. Firefighters flushed the house with fire hoses, and police violently removed people. In the end, one MOVE member shot and killed Officer James Ramp. Eighteen police officers and firefighters were hurt in the incident.

Delbert Africa maintained that he did not fire a gun that day, but was charged with third-degree murder and eventually sentenced to 30 to 100 years in state prison.

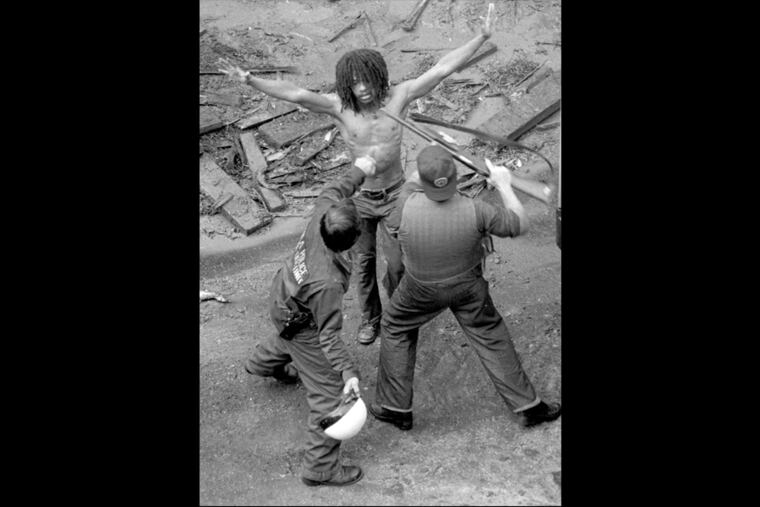

After surrendering with his arms outstretched, a moment captured in a harrowing Inquirer photograph, he was beaten by officers, he recalled.

“I’m unconscious, and that’s when one cop pulled me by the hair across the street, one cop started jumping on my head, one started kicking me in the ribs and beating me," he said in January. “Their excuse later on is they thought I was armed. I was naked from the waist up.”

He added: “Nothing could have been done differently to stop and curtail that assault by the police on us. It wouldn’t have stopped."

In 1980, MOVE relocated to the 6200 block of Osage Avenue, and quickly came into conflict with neighbors, who complained to the city about trash, loudspeaker speeches and suspicions of child abuse and neglect.

On May 13, 1985, the city flew a helicopter over the group’s home and dropped a bomb that left 11 people dead, including John Africa, as well as Delbert Africa’s 13-year-old daughter. An additional 61 homes were destroyed by the bombing and the resulting fire, and the incident became international news.

Pam Africa said that while Delbert Africa had less than six months of freedom at the end of his life, it was time well spent.

“He had a full six months on the street, because he was very well loved by everyone. When he was in the hospital, people wrote him letters. When he came home from the hospital, he came with letters from doctors and nurses. They knew who he was. He was respected,” she said.