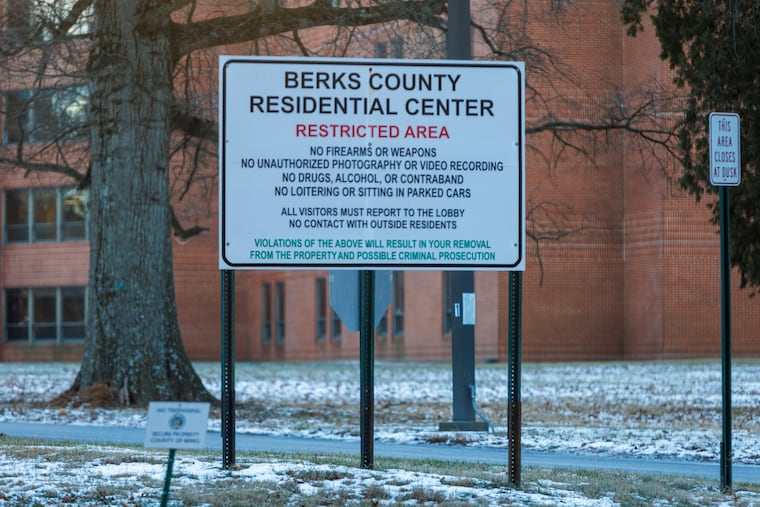

Pennsylvania’s immigrant ‘baby jail’ was notorious. Now Trump may revive family detention for children and parents.

The new administration promises to dramatically increase immigration enforcement and deport millions of undocumented people

Critics who fought to close the Berks County immigrant-detention center called it a “baby jail,” a place that confined small children along with their parents.

The facility drew lawsuits and protests and brought international attention to Pennsylvania in 2019, when it held a 3-month-old boy in what his mother described as filthy and frigid conditions. The British father, mother, and child were imprisoned after making what they said was a wrong turn at the Canadian border and federal officials said was a deliberate attempt to illegally enter the United States.

Now the incoming Trump administration intends to revive the highly controversial practice of family detention — which ended under President Joe Biden — and hold parents and children in the same jail while their cases proceed through immigration court. An ICE spokesperson said the agency has no plans to restore Berks or to establish a new center elsewhere in Pennsylvania, but people who advocate for migrants wonder if family detention could reemerge in the Keystone State.

“That’s wait and see,” said Jasmine Rivera, who led the Shut Down Berks Coalition and now runs the Pennsylvania Immigration Coalition, an advocacy group based in Philadelphia. “It’s 100% possible we could see some other type of facility.”

Today, on the cusp of President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration, the operation of the Berks facility offers insight into how renewed family detention could function. The new administration promises to dramatically increase immigration enforcement and deport millions of undocumented people — potentially including about 47,000 in Philadelphia and 153,000 statewide.

The 96-bed Berks site in Leesport, about 75 miles northwest of Philadelphia, operated as one of three family detention centers in the United States. It was by far the smallest, the other two, in Texas, having a shared capacity of 3,000.

Berks was run by the county through a contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE officials let the contract expire in early 2021, saying tax dollars could be better spent on facilities that offered greater performance, efficiency, and economy of scale.

Until then, immigrant families were sent to Berks from across the United States. Most had been stopped at the U.S. southern border, generally mothers and children seeking asylum, a legal means for people who face danger in their homelands to stay in the United States.

According to ICE, those families, like other foreign nationals, were held to make certain they attended their immigration hearings, and so that if necessary they could be readily deported. Some migrants are subject to mandatory detention under the law, and the agency has deemed others to be public-safety or flight risks.

At the time Berks was operating, ICE officials said what was officially called the county residential center was an “effective and humane” means of housing families, a place with playrooms, educational services, and access to legal counsel and medical care.

After closing for family detention, Berks reopened in 2022 to hold immigrant women, and now serves as the county Youth Center, which houses a shelter program for up to 20 young people with behavioral, mental, and developmental disabilities.

Berks County officials told The Inquirer they have no plans to offer the property to the Trump administration. And no one from ICE or the administration has asked about its availability, according to county spokesperson Jonathan Heintzman.

But family detention is coming back, according to Trump officials.

Incoming “border czar” Tom Homan told the Washington Post that authorities plan to hold parents and children in “soft-sided” tent structures as part of the administration’s escalation of enforcement. So-called mixed-status families — where, for instance, the children may be U.S.-born American citizens and the parents undocumented — will have the option of being deported together or splitting up, he said.

Cris Ramon, senior adviser on immigration for UnidosUS, the Latino civil rights organization in Washington, said he expects legal challenges could complicate the administration’s efforts.

“These actions to arrest and hold children, or try to hold children, are going to be generating a lot of social harm,” he said. “We’re talking about real human lives that are going to be derailed and negatively impacted by these proposed actions.”

Immigrant-advocacy groups argue that nearly everyone who was held at Berks — or who may be jailed at similar facilities in the future — could be released on bail or to family members or community sponsors instead of being confined.

President-elect Trump has pledged to start his mass-deportation program by removing immigrants convicted of crimes. None of the families held at Berks faced criminal charges.

“If what they’re interested in is deporting criminal offenders, or people who pose a security risk, family detention is not it,” said Reading attorney Bridget Cambria, executive director of Aldea — the People’s Justice Center, who sued the government dozens on times on behalf of families held at Berks. “The lesson from family detention is it failed. It only served to hurt children and families.”

Amnesty International and other watchdog groups condemned Berks as inhumane to the people held there and expensive for taxpayers.

A study by the nonprofit Human Rights First said in 2015 that children held at Berks experienced depression, anxiety, and increased aggression toward parents and other children. Many families already suffered trauma and abuse in their homelands, and detention worsened their conditions, the report found.

In 2016 a 40-year-old guard at Berks pleaded guilty to institutional sexual assault against a 19-year-old Honduran woman, the same year that two dozen female detainees undertook a hunger strike to protest their confinement. At one point in 2019, Berks held enough children to open a day-care center, including two 1-year-olds, two 2-year-olds, two 3-year-olds, a 4-year-old, and two 6-year-olds.

A main goal of family detention is to try to dissuade undocumented families from improperly entering the United States.

Then-President Barack Obama expanded what was in 2014 a nearly extinct practice, dramatically increasing the detention of women and children in what was called “an aggressive deterrence strategy” against tens of thousands of asylum-seekers arriving from Central America. The number of family detention beds surged from 90 to 3,700 in a year, according to Human Rights First.

Trump sought to solidify family detention during his first administration, promising to end what he called “catch and release,” which allowed migrants to live freely as their court cases proceeded.

Family detention puts pressure on parents to drop their cases and accept deportation as they see their children suffer.

Immigration advocates say that strategy never really worked in Pennsylvania.

Berks was far from the border, complicating deportation logistics. The mothers joined in communal opposition to confinement. And, crucially, the families had access to legal resources, with a group of immigration attorneys in the area offering assistance.

All of that has lawyer Cambria betting against a return of family detention in Pennsylvania.

“It didn’t work before,” she said. “I think they’ll do it in a way that’s ‘effective.’ They won’t create one that won’t meet their goals.”