Bill would bar Philly from keeping Social Security payments meant for foster children

The legislation would end a legal but controversial practice of transferring the money into the city’s $5 billion general fund.

City Councilmember Helen Gym plans to introduce legislation this week in response to a December Inquirer report that found the city has been taking millions of dollars in Social Security benefits belonging to children in foster care and plowing them back into the city’s general fund.

Gym’s legislation would end the practice, requiring the city to save the money for the youths themselves.

“I was deeply upset reading the story,” said Gym. “There was no question we needed to take action, which is why we’re moving toward legislation and worked over the last several months for a complete package that puts young people first.”

Children can be eligible for Social Security benefits through Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a public benefit for mental or physical disability and financial need; or through Old Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance (OASDI), if a parent or guardian has paid enough into the Social Security system before retiring, becoming disabled, or dying. This “survivor’s money,” as it’s usually called, is owed as an insurance payment to children and belongs to them.

However, because young people are legally considered incapable of managing their own money prior to reaching 18, they are assigned a “representative payee” to receive and manage those funds. In the case of youths in foster care, government child welfare agencies can step in to become that money manager.

Between fiscal years 2016 and 2020, the city took almost $5 million in Social Security benefits due to hundreds of children in foster care, according to city documents obtained by Resolve Philly and The Inquirer through a Right-to-Know request. The city transferred the money to its general fund, the records also showed, ostensibly for the purpose of compensating itself for the cost of room, board, and other services.

Federal law requires agencies to provide these services without passing the cost along to the children, and those without such funds aren’t required to reimburse agencies for their expenses.

In a typical year, DHS took about $1.3 million in benefits from about 380 youths in foster care. Records requests also showed that the city has no process in place to notify kids or their legal representatives that the money is being taken, preventing them from securing the money themselves.

» READ MORE: READ MORE: Philly took $5 million in foster children’s Social Security payments without telling them

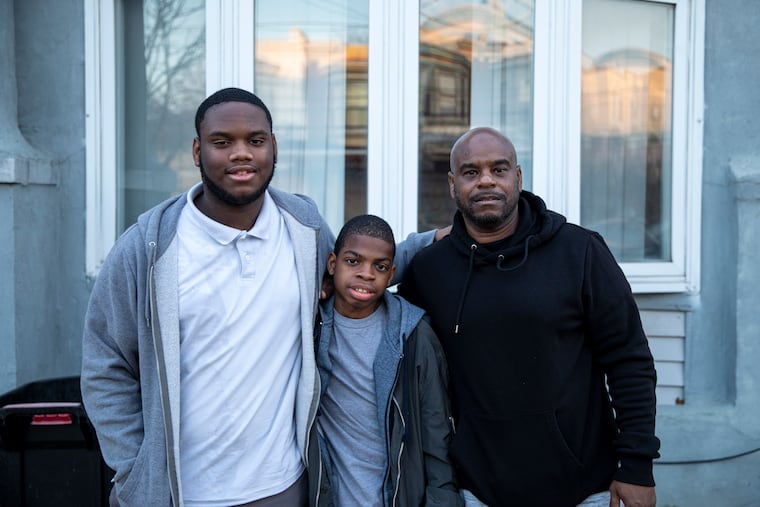

Vaughn Jackson, a longtime Philadelphia boxing trainer, discovered late last year that two boys for whom he serves as legal guardian were losing benefits when he was denied Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program funds. “They told me I was receiving too much money,” he said. “But I wasn’t receiving any money, and neither were the kids.”

With the help of attorneys at Community Legal Services, Jackson discovered that the money being paid out in the children’s names was actually being sent to DHS. In fact, the agency had been collecting survivor’s payments due to the boys from a previous adoptive parent for at least three years, including for nine months after Jackson had become their legal guardian.

“I feel like justice is being served,” Jackson said of Gym’s proposal. “It’s about time that people recognize: These orphans, they’re out there alone. They’re scared, and there’s enough trauma in their lives. They could look forward to having something for themselves.”

An NPR/Marshall Project investigation and figures gathered by the research organization Child Trends show that in at least 49 states child welfare agencies grab Social Security benefits from kids to pay for their own foster care, taking in at least $165 million in 2018 alone, for instance. The practice has also become subject to increasing calls for reform.

Courts in Maryland and Alaska have held that agencies violated foster children’s due-process rights when they took their benefits without informing them or their legal representatives. Maryland later enacted a law that mandates, among other things, that foster youths, or their lawyers, receive notice, allowing them an opportunity to claim the money. The law also calls for increasing amounts of their Social Security money to be set aside for them as they approach age 18. New York’s Administration for Children’s Services is voluntarily discontinuing the practice, opting to save funds for the individual youths to whom the money belongs.

Gym’s bill would require that savings accounts be opened for children receiving social security benefits. It also prohibits the city from using any of the youths’ benefits to cover the costs of their care. The bill would allow Philadelphia, in consultation with the child and their attorney, to potentially use some money for services not covered by foster care funding or health insurance, such as additional tutoring, disability aids, or a car.

Gym said her office is working “so far, collaboratively with DHS, and we’ve been told they’re open to ending the practice, and we’re working to find a good solution.”

A DHS spokesperson responded via email: “We are currently exploring various ways to make improvements to the practice that will better serve children and youth, both while they are in care and when they exit DHS custody. We look forward to working with Councilmember Gym, our colleagues at the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, the Social Security Administration, and other community stakeholders as we work through the complicated process to resolve this issue.”

The legislation could make thousands and even tens of thousands of dollars available to youth as they exit or age out of foster care, a critical period in transitioning to adulthood. Jackson’s wards, for example, each received a check for more than $9,000 to cover the period when they were out of DHS’s care.

Gym figures to find significant support among at least some council members who expressed concern or outrage.

City Councilmember Cindy Bass has stated her desire to hold hearings on DHS’s practice, seconded by Councilmember Isaiah Thomas.

“I absolutely support hearings,” said Thomas. “That report was disturbing and disappointing, and we’ll have to examine how we as a legislative body can resolve it.”

“We need, first, to stop this practice,” said Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, who found The Inquirer report “shocking” and “troubling.”

“When we talk about our country’s broken social safety net, this is what we mean,” said At-Large Councilmember Kendra Brooks. “Social Security payments should be going into the pockets of the children in foster care and their families who need that money, not the publicly funded institutions designed to serve them. We need to stop treating poor people, working class people, and people with disabilities like they can’t care for themselves.”

“This is another example of why we need to create a more efficient and humane system,” said Councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez. “We have kids suffering, who need this money and to whom it belongs. Why would we keep it and not give it to them?”

While many children leave foster care and go on to lead successful lives, foster alumni also face steeply increased risks of experiencing homelessness, substance addiction, increased health-care needs, and joblessness.

Marcus Jarvis spent many years in the city’s foster care system, and fits the pattern of someone who might have received social security benefits that were swept away from him and into the city’s coffers after the death of his adoptive mother.

“Man,” he said. Some cash “would have meant so much. I couldn’t keep up with school because I needed money just to keep a roof over my head.”

Now 30, Jarvis taught himself digital video production and graphic design and works for Juvenile Law Center, a nonprofit that fights for youth rights. “It was such a struggle,” he said, “for so long. I could have used that money just to get some stability to get some kind of college degree. … That would have changed everything.”

The Philadelphia Inquirer is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. See all of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.