Outrage over police injustice is older than the nation

After Africans from Angola were taken to Virginia in 1619, the colony passed laws to declare that black people had no rights to liberty or life. This would become an indelible idea in America.

The pain behind the protests across the country has been about more than the death of George Floyd.

Or Breonna Taylor, or Ahmaud Arbery. Or Tony McDade.

“This is hundreds of years of pain,” Jamal Crawford, a former Phoenix Suns basketball player, wrote on Twitter on Sunday, the day after peaceful protests in Philadelphia deteriorated into violence.

It was horrifying and enraging, watching Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin press his knee onto Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes, killing him.

But the pain and anger shaking black Americans over callousness toward their lives runs 400 years deeper.

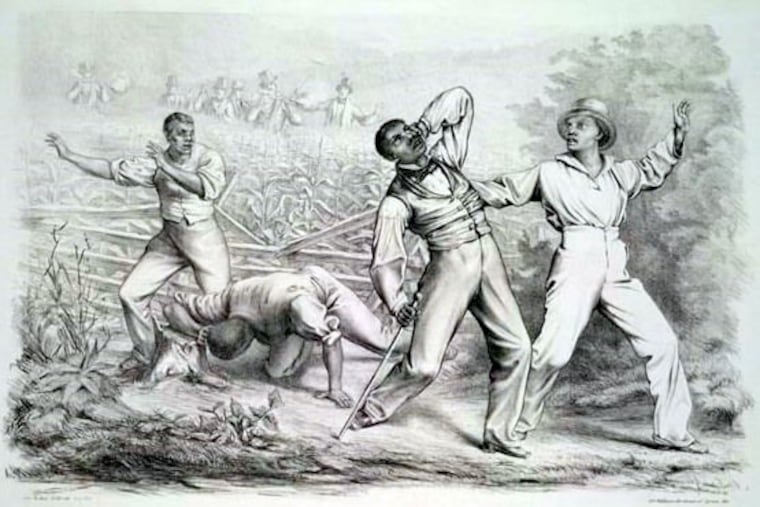

After Africans from Angola were taken to Virginia in 1619, the colony passed laws to declare that black people had no rights to liberty or life. This would become an indelible idea, activated through slave patrols and embedded into the future nation’s consciousness before it was even born.

“There clearly were laws on the books that said killing a runaway slave wasn’t seen as a crime to humanity, but as a property crime,” said Mark Anthony Neal, Duke University professor of African and African American studies.

A sheriff, an overseer, or any other white person who killed an enslaved black person who resisted capture would not face criminal charges. However, the white “property owner” could be compensated from public funds.

“Those were the rights that were protected," Neal said.

In 1680, the Virginia General Assembly enacted its first major slave code, restricting black people’s rights to assemble, move about, or carry guns.

» READ MORE: Protesters in Philadelphia demand police reforms, and elected officials say they’re listening

The law, “An act for preventing Negroes Insurrections,” said:

“And further, if any Negro … absent himself or lie out from his master’s service and resist lawful apprehension, he may be killed… .”

A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., the late Philadelphia federal judge, outlined early laws based on skin color in his book, In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process.

By 1705, a new Virginia law had increased white control over black lives. One section "provided that a master who killed his slave in an attempt to ‘correct’ the slave would not be held to have committed a felony,” Higginbotham wrote.

But, it went on, "the master, owner and every such other person so giving correction, shall be free and acquit of all punishment and accusation… as if such accident had never happened,” the 1705 law read.

Floyd’s killing ignited such widespread outrage not only because it followed so closely the killings of Taylor and Arbery, but because a video gave chilling witness to his calling out in pain, desperate to breathe.

“This one is so graphic that you can see [his death] with your own eyes,” said Mary Frances Berry, who is Geraldine R. Segal professor of American social thought and professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania.

The country never truly addressed the foundation of earlier riots, or rebellions, Berry said, by reforming policing policies and punishing officers who killed innocent people, or by improving economic and educational opportunities.

» READ MORE: ‘Police just went nuts’: Charges dropped after video surfaces of police beating student, other protesters with batons

Following rebellions in Los Angeles in 1965 and in dozens of cities in the summer of 1967, the Kerner Commission issued a report in 1968 saying:

“What white Americans have never fully understood but what the Negro can never forget — is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

The Kerner Commission argued riots were caused mainly by poor neighborhood conditions and limited job opportunities due to racism.

But, Berry said, “every one of those riots in the ’60s were set off by police harassing somebody, or beating somebody."

“And every single time that happens, they increase resources for police for them to beat up on people, and they give them more equipment. They don’t really do the things the report tells them to do.”

Berry, a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights from 1980 to 2004, said the killing of Floyd touched off a storm of response because of “multiple pandemics” — of COVID-19, which disproportionately kills people of color, a startling unemployment rate, and an economy reminiscent of the Depression.

This all adds to the pressure many Americans feel, she said, but African Americans are feeling those pressures more acutely.