A Malvern family recalls the horror of the Highland Park Independence Day Parade

Seven people were killed when a gunman used an AR-15-style rifle to shoot onlookers at a July 4th parade in suburban Chicago.

When the staccato crack of an AR-15-style rifle rang out over the July Fourth parade in suburban Illinois, the little boy thought someone was popping balloons.

“I’ve been hit; get down,” his mother, Ashlee Jaffe, yelled to no one in particular, as the shots were fired.

Jaffe, 39, a pediatric physiatrist at CHOP, felt a burning in her arm and saw blood on her hand. She wasn’t sure if a bullet ricocheted off the ground or passed through someone else’s body before it struck her. She dropped to the ground, just outside the Highland Park pancake house where she’d celebrated her dad’s birthday a day earlier, and wedged her son, Caidyn, under a bench, pressing her body against his.

“I heard my son screaming ‘Mommy, Mommy,’ ” she recalled Thursday from her home in Malvern. “It was all quieter than you would imagine. "

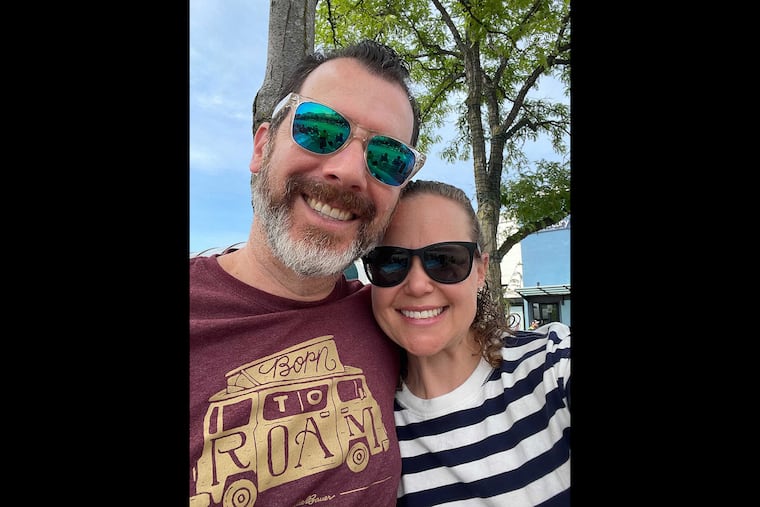

Ashlee Jaffe, who grew up in Northbrook, one town over from Highland Park, had taken a selfie with her husband, Brian, by the parade route at around 9:55 a.m. to celebrate their seventh wedding anniversary. They were married on the Fourth of July.

Twenty minutes later, they parted ways in a panic. She tried to help the wounded and get medical treatment for her hand. Brian, 46, took their son and a friend’s child to safety. Caidyn, who recently turned 5, has been repeating something his father said to a man walking toward the parade as they fled, someone seemingly unaware that an active shooter had opened fire amid the wailing fire engines and marching bands there in middle America.

“My daddy told the man ‘there’s a shooter, you have to run,’ ” the boy has told people.

After hiding behind a brick post, then hunkering down at a construction site, Brian Jaffe was able to get Caidyn back to where they were staying. He changed the boy’s bloody clothes, then wiped blood from his face before Caidyn noticed it. .

“He wasn’t injured, so I wasn’t sure if it was his mom’s blood or someone else’s,” Brian said.

Seven people died that morning in Highland Park, with dozens more injured, and it’s left Caidyn with a growing list of questions. He wonders if Captain America and his mighty shield could have helped the SWAT team members he saw. Did they catch the bad man who did this? What is his name?

“Is this always what parades are like?” he asked his parents.

The Jaffes are back in Malvern now, the shock of what happened Monday morning still settling over their lives. Ashlee needed minor surgery on her hand but said there’s no structural damage. Caidyn was at a day camp when she spoke to The Inquirer Thursday afternoon, but there’s no telling how that morning in Illinois will affect his future.

“He’s still thinking of more questions,” Ashlee said. “You can tell he’s trying to piece it all together. He’s going to kindergarten and I wonder how he’ll feel about something like a Halloween parade. I fear he’s never going to have that joy of what a parade should be.”

The family’s trip to suburban Chicago for the holiday was Ashlee’s first time home in years, she said. The Highland Park parade seemed like a good way to pass time before their 3 p.m. flight back to Philly on Monday. Ashlee said the city, about 30 miles north of Chicago, is your “typical, idyllic American suburb with a small downtown.”

‘‘There are people there who are third and fourth generation, along with people who’ve come back to raise their kids in a safe, comfortable environment. It’s tight-knit,” she said. “I was seeing people I knew during the parade. I knew people who were on floats in the parade.”

Ashlee said the parade started off normally, like the thousands of others across the country that weekend.

“First it was mostly kids and pets, a bunch of kids and schools. There were motorcycles, wagons, strollers, and lots of dogs. I spent the first half hour waving at people,” she said. “Then it was what you’d expect. Flags and police and ambulances and fire trucks and firefighters waving from the windows. I remember seeing the high school marching band and convertibles with veterans sitting in them. The mayor of the town was there.”

The pop-pop-pop of the rifle took a moment to register. In a video shared on social media, onlookers don’t seem to react as the first dozen bullets are fired.

“The people there right next to me, they thought it was fireworks, or kids throwing poppers,” she said. “It wasn’t as loud as I would think. It took everyone by surprise.”

When Ashlee watches that video, she can see her husband’s leg. She can hear her son scream “Mommy.”

Some of the people seated near the Jaffes by the pancake house died that morning. Ashlee said she went to summer camp with one of them.

After the shooting, Ashlee initially sought help at NorthShore Highland Park Hospital. She was born there. It’s where her mother, Cindy, passed away in 2012. But she soon realized the small hospital was overwhelmed with victims. She tried to help people in the waiting room instead before leaving for another hospital.

“People just kept coming in,” she said.

The slayings, she said, left her with immediate observations about mass shootings. She recalled how middle and high school students, kids who’ve grown up in the world of active-shooter training, seemed calmer that morning.

“Most of the adults didn’t have a clue,” she said. “And it made me think, so few of us know what gunfire sounds like or what to do when we hear it.”

Brian and Ashlee agree that no American needs an AR-15-style rifle. The suspect bought the Smith & Wesson M&P 15, a semiautomatic weapon, legally. Police found 83 spent shell casings.

“One person, with this one single rifle, can cause so much damage, so quickly,” Ashlee said. “It’s incomprehensible. It doesn’t belong in the community.”

Brian said there were many armed police officers along the parade route before the suspect opened fire.

“No one fired a shot at the suspect the entire time,” he said.

Ashlee said every citizen across the country should know the same thing could happen to them and come up with a game plan. For now, she’ll focus on healing, on handling the coming questions she knows her son will have, and trying to prevent that morning in Illinois from taking root in her family’s story.

“Right now, there’s shock and moments of calm and moments of anger,” she said. “Mostly I’m trying to put on a face, some kind of normalcy for our son, because of what he experienced.”

She wants her son to believe, someday, that all parades aren’t like this in America.