In Philly, your house being ripped off isn’t always enough to get help from police and the DA

People whose houses have been stolen often face a bureaucratic maze in which Philadelphia police tell them to seek help from the district attorney, and the DA's Office tells them to go to police.

Earlier this year, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner mocked his predecessor for taking a lackadaisical approach to housing theft — the growing problem of grifters forging deeds and posing as heirs to steal properties. He said he was different.

The previous district attorney, Seth Williams, had a rule not to pursue cumbersome and paperwork-intensive cases of house thievery unless the crook swiped at least 20 homes, Krasner said.

“Imagine a world where we only went after car thieves when they hit number 20,” Krasner said in February. “Well, that is not how it works anymore.”

It turns out Krasner left out part of the story.

His office still won’t investigate allegations of house theft that involve only one property, his staff recently confirmed. Nor does it have the staff to investigate every complaint, the lead prosecutor for house thefts said. Instead, the office often tells victims who have had a single property ripped off to go to the police.

If police then do build a case, the District Attorney’s Office will prosecute. Assistant District Attorney Kimberly Esack said that’s an improvement from past district attorneys who she said would decline to prosecute single-theft cases.

Since February, Krasner’s office has announced criminal charges against six suspects for multiple-house thefts. Prosecutors, in cooperation with police, have brought one case involving a single property theft.

Krasner’s spokesperson, Jane Roh, said there was nothing misleading about Krasner’s statement.

“District Attorney Krasner has absolutely shifted the mission of this office away from callousness toward low-income vulnerable people and toward remaking a system of justice that works fairly and effectively for everyone,” she said.

“If we had the resources that I believe we need, then we would go after everything if we could," she added.

Some victims who have been recently rebuffed decry the district attorney’s practice. They tell of being trapped in a maze of bureaucratic pass-the-buck in which police tell them to seek help from the DA and the DA tells them to go to police.

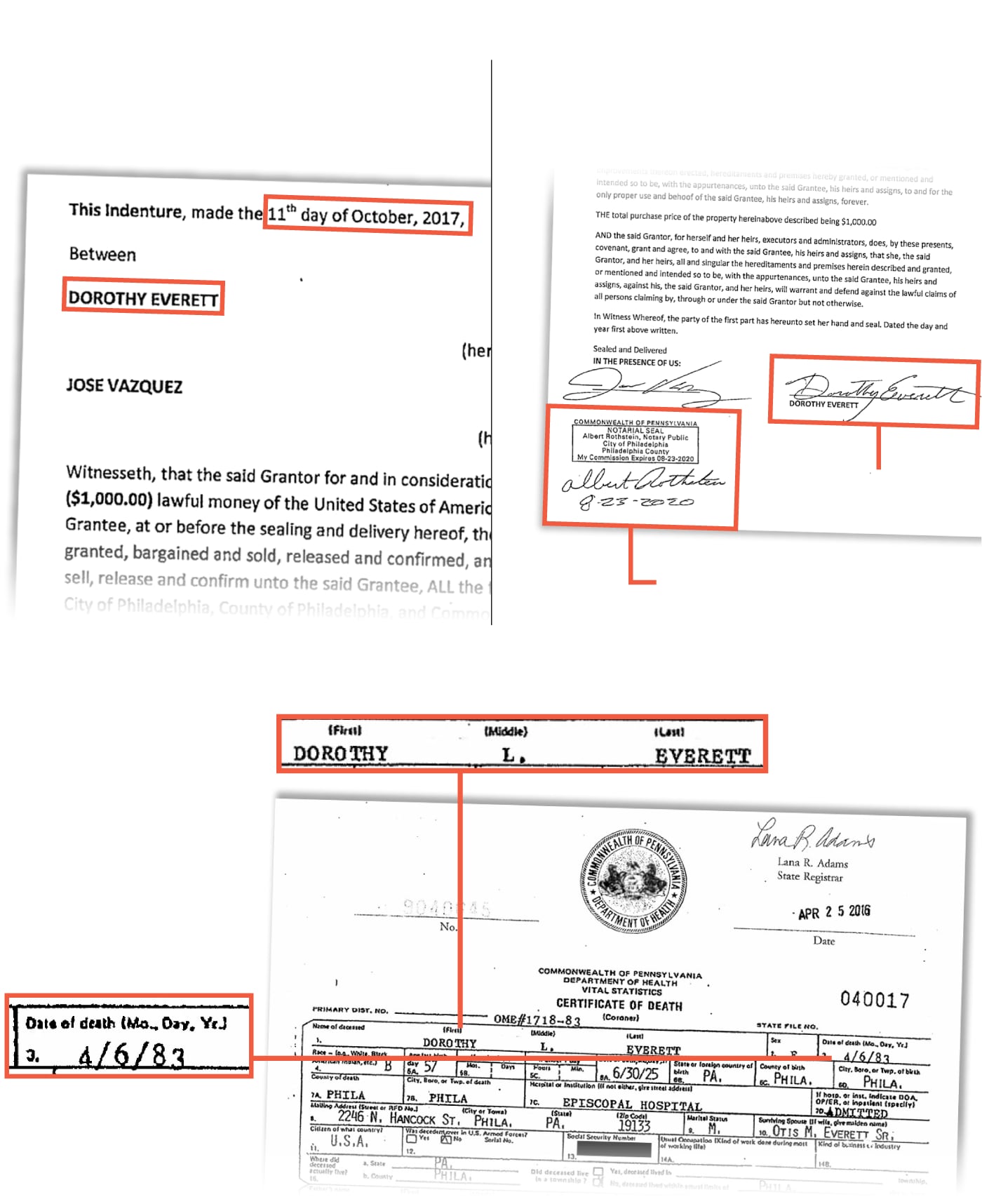

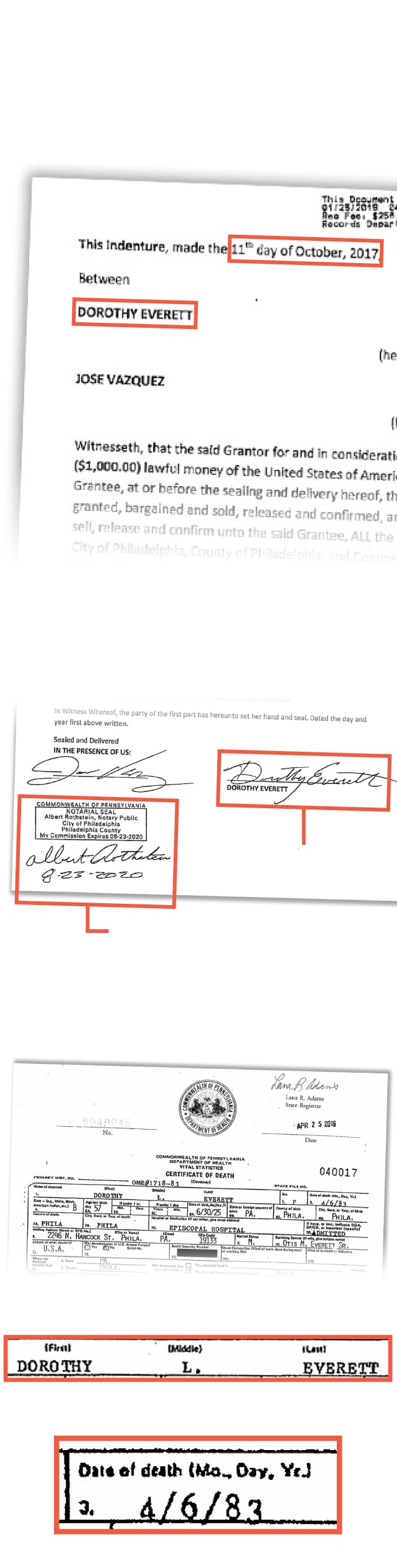

One victim who says her family got the brush-off from both police and prosecutors is Shannon Driggins, 35, a state social worker. She discovered last year that a man named Jose Vazquez had filed a deed saying he had bought the family’s home on Hancock Street in Kensington from her grandmother in 2017.

The deed bore the signature of her grandmother. But she died in 1983, her death certificate shows. The deed says her signature was stamped and verified by a notary named “Albert Rothstein.” That’s faked, too. State regulators say there is no such notary in Pennsylvania. Vazquez did not respond to a letter seeking comment.

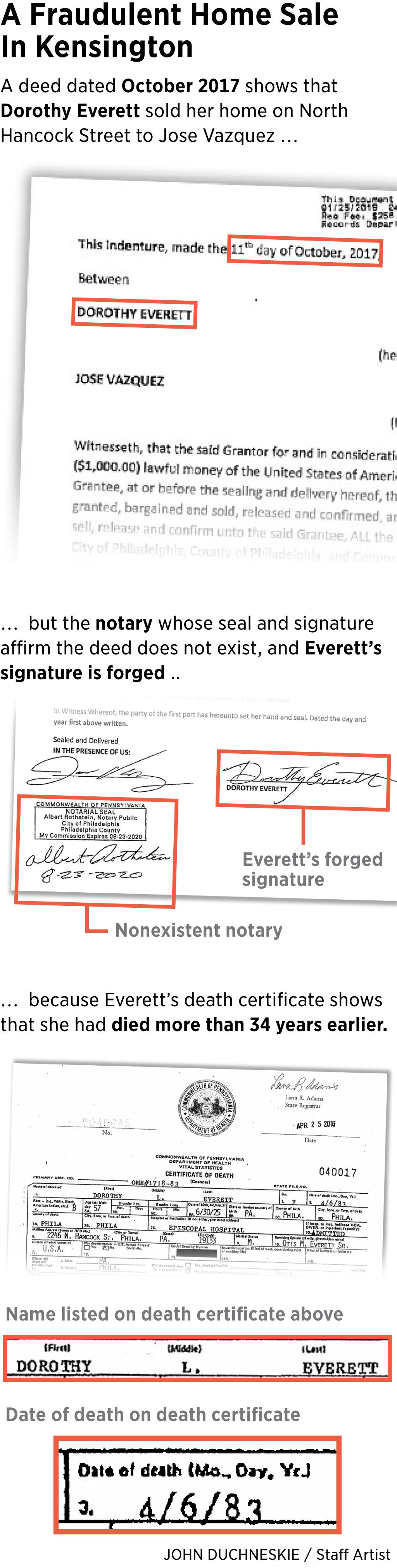

A Fraudulent Home Sale In Kensington

A deed dated October 2017 shows that Dorothy Everett sold her home on North Hancock Street to Jose Vazquez …

… but the notary whose seal and signature affirm the deed does not exist, and Everett’s signature is forged …

Everett’s forged

signature

Nonexistent notary

Name listed on death certificate below

… because Everett’s death certificate shows that she had died more than 34 years earlier.

Date of death

on death certificate

JOHN DUCHNESKIE / Staff Artist

A Fraudulent Home Sale

In Kensington

A deed dated October 2017 shows that Dorothy Everett sold her home on North Hancock Street to Jose Vazquez …

… but the notary whose seal and signature affirm the deed does not exist, and Everett’s signature is forged …

Everett’s forged

signature

Nonexistent notary

… because Everett’s death certificate shows that she had died more than 34 years earlier.

Name listed on death certificate above

Date of death on death certificate

JOHN DUCHNESKIE / Staff Artist

>> Reading on mobile and not seeing the graphic above? Click here to view the full version.

In early 2018, when Driggins called the police to report her house had been stolen, she says a detective laughed at her on the phone. She said he took no interest when she tried to provide descriptions of workers whom she had confronted inside the place fixing it up. She filed a complaint with police Internal Affairs about the detective. Internal Affairs said her complaint could not be verified, she said.

After months of on-again, off-again contact with the DA’s Office, Driggins went to the office’s lobby in June and called up, trying to get help.

A paralegal with the office’s Economic Crime Unit eventually texted her back.

“We have a record of your contacting our office in 2018 and that a NW detective was assigned,” texted Randy Kim. “We want to know why we are being contacted again.”

“You need to work with the police, and if they press charges, then our office will be responsible for the prosecution.”

Kim also wrote: “It is still the responsibility of local police to determine whether or not there is sufficient evidence to bring criminal charges which our office prosecutes. Depending on the complexity of the situation, you may want to hire a civil attorney to sue him and then use the successful prosecution to present to the police. This makes the matter much simpler and straightforward for law enforcement authorities.”

Not long after a reporter inquired about how the police handled cases of stolen homes, a detective with the Major Crimes economic-crime squad called Driggins last week and promised to investigate, Driggins said.

Roh said she could not comment on Driggins’ case but suggested prosecutors were also at work on it. “Stay tuned,” she said.

Like Driggins, Allen Odeniyi, 29, lost his house in West Philadelphia because of a fake deed. He says his signature was forged in 2018 to a deed in which the building was acquired by a Priscilla Welcome.

He says he called both the police and District Attorney’s Office and got no help from either.

A detective in the Southwest Division heard the account and urged Odeniyi to file a lawsuit. While the detective promised to investigate, Odeniyi recalled, “he predicted that as a one-house theft, not much would happen.” Odeniyi said he called the detective back several times, but never heard from him again.

He said the message was the same at the DA’s Office: “I was told if it’s a one-off case, they wouldn’t pursue it as aggressively as they would pursue a ring of multiple cases."

Odeniyi said he was aware of the demands facing law enforcement but was left wondering why he had reported the crime in the first place.

“On the one hand, I understand you can’t chase every lead because there are limited resources,” he said. “At the same time, you don’t want the public to lose trust.“

It was only after suing in Common Pleas Court and spending $15,000 that Odeniyi obtained a ruling in January that restored his ownership.

Priscilla Welcome, who took ownership of the home last year, said in an interview that she, too, had been victimized — by a middleman who had brokered her acquisition. “The person who sold the property to me is a major scam artist throughout the city,” she said.

Told that Odeniyi was suspicious of her role, she replied that he could “kiss my entire backside.”

Prosecutors double — to two

A former top aide to the previous district attorney, Seth Williams, disputed Krasner’s criticism of his predecessor. Williams’ staff had no prohibition on prosecuting single-house cases brought in by police, the aide said. (He spoke only if not named because he did not want to get into a public disagreement with Krasner.)

In any event, Krasner only recently assigned one more prosecutor to join Esack in bringing house-theft cases. He also unsuccessully sought $3 million more in his budget for the fiscal year that began July 1, Krasner said, in part to hire more prosecutors to crack down on real-estate crimes.

Roh said that Mayor Jim Kenney and City Council had in fact cut the district attorney’s budget; she said Krasner would keep pushing for the new funding.

Mike Dunn, Kenney’s spokesperson, said the administration found Krasner’s complaint “perplexing” given that the district attorney “had been unable to spend the full amount” given him in past years.

Prosecutor Esack says that on a bad day, her office may field as many as five fresh complaints of property theft. Esack says she carries a caseload of 50 cases at any one time, including identity thefts and more.

In his February remarks, Krasner said he had pushed for a “rebuilding and expansion of our economic crimes [unit], so it is a little bit more oriented toward taking care of vulnerable populations, as opposed to insurance companies.”

His office, like district attorneys dating to 1995, has a subsidized unit to investigate insurance fraud. It is paid for with a $3 million annual grant from the insurance industry — and has a staff of 18, including about five prosecutors.

Critics say more resources and tougher law enforcement is the key to squelching an epidemic of house theft in the city’s gentrifying neighborhoods. The city Records Department said complaints hit 136 last year, nearly 60 more than the previous year.

Neither of the Driggins or Odeniyi forgeries was flagged in the department’s City Hall deed room, which has not had an increase in staffing — currently 18 — even as filings have increased, city budget documents show. About 33,000 deeds were filed five years ago. Last year, the tally exceeded 41,000.

Input from police to prosecutors has been minimal. Police Lt. Jonathan Josey, a spokesperson for the police’s economic-crimes squad, which investigates house theft, said its only referral to prosecutors in recent months was about two stolen houses that Esack made part of a larger case against a ring accused of stealing 21 properties.

Josey said he commands six detectives and one police officer. The squad’s portfolio includes a wide range of white-collar crimes besides deed forgeries.

“I would like to have more [staff]. But we are a very, very violent city,” he said. “But we would like to have more because this crime is on an uptick.”

Staff writer Nathaniel Lash contributed to this article.