Muslims in Philadelphia face more housing disadvantages than non-Muslims, report says. Some Philly Muslims don’t see a problem.

In Philadelphia, Muslims are less likely than non-Muslims to live in predominantly white neighborhoods, a new study finds. Among black Americans, non-Muslims are more likely to live in the suburbs.

In a new report drawn from a case study of Philadelphia, Muslims were found to face more housing inequality, or “residential disadvantages,” than non-Muslims.

“Muslims live in neighborhoods that have significantly lower shares of whites and greater representations of blacks," the study, published last month in the journal Demography, concluded. Furthermore, "among blacks, Muslims are significantly less likely than non-Muslims to reside in suburbs.”

Samantha Friedman, a co-author and an associate professor of sociology at the University at Albany, State University of New York, said Philadelphia was chosen because its Muslim population of about 1% mirrors trends in metropolitan areas across the country. However, it is unique among American cities in that the majority of its Muslim residents are African American, whereas nationally, blacks are only 20% of the faith.

Philadelphia was also selected for the study because the metropolitan region ranks fourth in the country in the number of mosques.

The report — “Muslim-Non-Muslim Locational Attainment in Philadelphia: A New Fault Line in Residential Inequality?” — is described by its authors as likely the first U.S.-based study on the subject.

“We find that Muslims experience greater residential disadvantage than non-Muslims in Philadelphia," the report said. "Moreover, black Muslims face a double disadvantage due to both their race and their religion.”

Friedman sees that as “a barrier to having access to better neighborhoods and better schools.”

"Predominantly white neighborhoods offer the best access to educational opportunities, economic opportunities, and they have better environmental quality,” she said.

However, the study concedes it cannot explain why Muslims — even those with higher incomes — tend to live in majority black or Hispanic neighborhoods.

“We don’t know for sure why there’s this disparity," Friedman said. "Could it be because they have faced discrimination and end up living in neighborhoods with more blacks? Or could it be that they prefer to live in a more diverse neighborhood and a less white neighborhood?”

The researchers studied household surveys conducted in the Philadelphia area in 2004, 2006, and 2008, containing information on religious affiliation, race, socioeconomic status, and demographic data. They combined that with information on neighborhoods from the 2005-09 American Community Survey.

Some Philadelphia-area Muslims reacted to the research by saying they don’t believe Muslims face housing bias due to their religion.

Kenneth Abdus Salaam, an African American Muslim who as a teenager in 1965 marched against segregationist policies at Girard College, said he hasn’t heard complaints from Muslims about housing discrimination.

“One thing about Muslims, one of the concepts, is to establish a community,” said Salaam. “Among the African American community, a lot of people try to live around the mosque where they pray.”

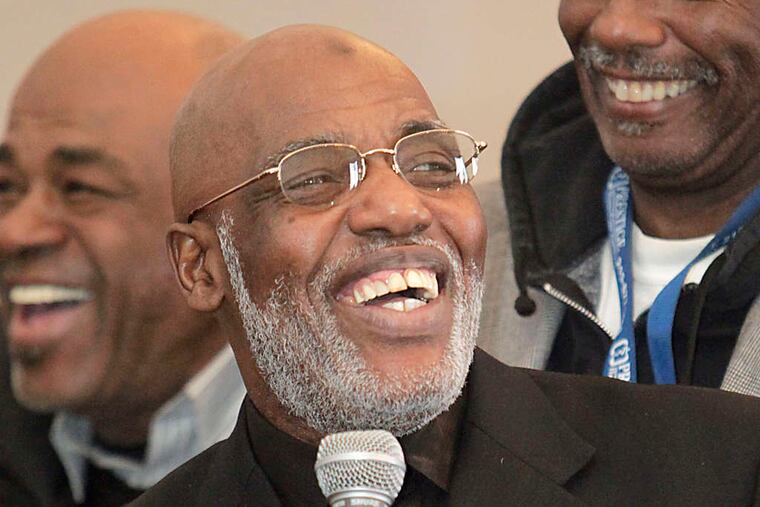

Rodney Muhammad, a Muslim and president of the Philadelphia NAACP, agreed.

“I think I would have heard of it, if there was real housing discrimination based on religion,” he said.

He said he worries, however, about the kind of discrimination that places much more value on a house in a white neighborhood, even though it may have fewer amenities, than a similar house in a predominantly black neighborhood.

“You can go to an all-white community and see a three-bedroom house that may have an unfinished basement and no garage, and it’s worth $250,000,” Muhammad said. “But you go to a neighborhood that is mainly black, and have a three-bedroom house with a finished basement and a garage, but somehow the house in the black neighborhood is worth almost $50,000 less.”

He said the NAACP is working with state officials to address that, as well as the denial of mortgages to black families.

Marwan Kreidie, executive director of the Arab American Development Corp. and a spokesperson for Al-Aqsa Islamic Society, a mosque at 1501 Germantown Ave. with a mostly immigrant congregation, also said members don’t talk about housing discrimination.

“It’s not like Arabs are not discriminated against, but they don’t look black," Kreidie said. "And in America, that’s the real issue.”

While Arab people “can come in all shades,” he added, “the ones who are darker, the ones who tend to look more Arabic, get more discrimination. But the ones who are whiter don’t. This is America.”

He said many highly educated immigrant Muslims live in the suburbs with few problems.

“The only housing issue we’re facing now in the community living near Al-Aqsa is gentrification,” he said. The mosque is in a North Philadelphia neighborhood just north of Northern Liberties and west of Fishtown.

Kreidie said the Arab American Development Corp. recently built 45 units of affordable-housing apartments in the neighborhood. The majority of the tenants are African American and Latino. One-third are Arabs and Muslims, he said. “It’s what we wanted it to look like, like the neighborhood.”

Until recently, many immigrant and first-generation Muslims lived in mostly white suburban communities without facing discrimination or hostility, said Jacob Bender, executive director of the Council of American-Islamic Relations in Philadelphia, a civil rights organization that advocates for Muslim Americans.

However, since 9/11 and, more recently, since President Donald Trump called for “Muslim bans” on immigration, those Muslims have started to experience anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim bigotry, he said.

“For many of them, having economic success was a guarantee of living in a hate-free, bigotry-free environment," Bender said. "Then along came 9/11, and the election, and reversed that.”

Friedman and her co-authors wanted to examine Muslims and housing disadvantages in light of other research showing that anti-Muslim sentiment has been growing in recent years.

“Between 2003 and 2014, the share of Americans disapproving of their child marrying a Muslim increased from 34% to 50%, with Muslims comprising the least desirable marriage partners compared to atheists, gays, Jews, and African Americans,” she said, referring to a study at the University of Minnesota.

Friedman said that Muslims may prefer to live in “majority-minority” or predominantly black or Latino neighborhoods because of strong social networks and connections to people who have known their families for generations.

“In the short term, they may have someone to watch their children while they work,” she said. “But in the long term, the impact may be more negative, because they will not have access to people from the majority community [who are white] who have networks that can lead to job opportunities and social mobility."

Philadelphia is known for being “hyper-segregated," a designation scholars have used in reference to the city since the 1970s, Friedman said. Simply put, it means that white and black people tend to live in different neighborhoods.

"Hyper-segregation has resulted in better neighborhood conditions for whites, including better school quality, access to jobs, health-care services, and lower levels of crime,” the report said.

But Friedman suspects anti-Muslim bias is a factor in the “residential disadvantages” Muslims face and said a goal of the report is to raise awareness.

“Muslims should know their rights and that there are protections under the Fair Housing Act,” she said.