How do you teach 9/11 to students too young to remember? Philly-area educators tell how they make it real.

Kevin Tamasitis was a seventh grader on 9/11. Now, he’s a seventh grade teacher at Wagner Middle School in the West Oak Lane section of Philadelphia.

Even the oldest young people in school today — university students included — have no memory of the events that unfolded 20 years ago this Saturday, when the crashing of four planes brought sudden catastrophe to so many American lives.

At the same time, the way the country has come to understand what happened and why has matured in the last two decades.

We talked to educators around the region — some whose own lives permanently changed course because of 9/11 — about the ways they bring resonance to the events from 2001, how their teaching may have evolved, what they do to bridge it to the now, and the one thing you need to get a reaction (hint: connection).

‘They have this visceral reaction’

Kevin Tamasitis was a seventh grader on 9/11. He still remembers where he was sitting in his classroom at St. Charles Borromeo School in Bensalem when he heard the news, the direction his teacher’s desk faced, who was sitting next to him.

Now, he’s a seventh-grade teacher at Wagner Middle School in the West Oak Lane section of Philadelphia, preparing to teach children about a seminal event in U.S. history — and in his own life. Tamasitis is a teacher but also a member of the Pennsylvania Army National Guard — and the things he felt watching the towers fall as a 12-year-old were part of the reason he enlisted in the military.

Tamasitis’ students typically come in with little understanding of what the day was about. He keeps the focus basic: What is al-Qaeda, the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and Flight 93?

» READ MORE: Stewards of sacred ground

He asks them what the single biggest historical event of their life has been — most say the Eagles’ Super Bowl victory, Tamasitis said — and tells them his seventh-grade story. Tamasitis and his students compare and contrast life before 9/11; the preteens can’t believe people used to be able to just walk to an airplane gate without a ticket, without a full-body scan.

Every year, he shows them part of a documentary about the life of Welles Crowther, a 24-year-old who saved at least 10 people from death in the South Tower before losing his own life. Crowther, known as “the man in the red bandanna” for the face covering he wore as he made multiple trips back inside to rescue people, loved lacrosse and his family and worked as an equities trader. He was one of myriad heroes in an unspeakable tragedy.

“They have to make a connection,” said Tamasitis, 32. “The kids learn about the man in the red bandanna, and all of a sudden they have this visceral reaction — it’s real for them.”

It’s a weighty lesson, but it’s one Tamasitis relishes teaching.

“I just don’t want them to forget 9/11,” he said.

There’s a history that’s been ‘completely neglected’

As a parent, Ameena Ghaffar-Kucher knows what usually gets taught about Sept. 11: stories about heroes and remembrance, about the way Americans felt that day, and about the fundamentals of the attacks. But Ghaffar-Kucher, senior lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education, wants high school and college teachers to do more.

“Those are important,” Ghaffar-Kucher said, “but they can’t be the only stories.”

Ghaffar-Kucher has worked with experts from around the country and around the world — all Muslim or people of color — to develop “Teaching Beyond Sept. 11,” an interdisciplinary curriculum about the ongoing global impact of 9/11. There are lessons about democracy and rights, media and representation, foreign policy, and public opinion and anti-Muslim sentiment.

That is: Many students don’t realize the United States has been at war for the last 20 years. They haven’t examined the Patriot Act, or how Islamophobia ratcheted up dramatically over the last two decades, or thought about the events that led to President Donald Trump’s executive orders banning foreign nationals from several Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States. Sept. 11 contributed to all of those events.

“There’s history from the last 20 years that is completely neglected,” said Ghaffar-Kucher. “This curriculum is really speaking to that gap and helping young people understand just how the world has changed as a consequence of that awful day.”

These are tough subjects, no doubt.

“Some lessons will challenge students’ worldviews, while others might cause discomfort, especially for students from impacted communities,” Ghaffar-Kucher and the other Beyond 9/11 authors write. “As educators, we believe that some of the best learning happens outside of one’s comfort zone; that being said, it is imperative for educators to approach these topics with sensitivity so as not to reinforce stereotypes or create tensions within groups of students or foster disinformation.”

The aim is for the lessons to be used not just in social studies and history classes, but also by art and English teachers. There are more than 50 lessons over six themes, informed by a global media analysis of events between 2001 and 2021.

It’s a project of great importance for Ghaffar-Kucher, 43, who has researched immigrants for nearly two decades and who, as a public school parent in New York and Philadelphia over the last decade-plus, wanted teachers to have more tools to start conversations about a formative day in American history.

“We want people to have a long view of history, of this time period. And we want to keep this conversation alive long beyond September 11,” said Ghaffar-Kucher.

‘Suddenly, I had a role to play’

Before 9/11 happened, Barak Mendelsohn was an Israeli-born doctoral student at Cornell University with a relatively obscure existence.

“Nobody cared about me,” he recalled.

He was at the Ivy League university the day the planes flew into the twin towers. Then everyone wanted to know what the Israeli who studied security and terrorism in the Middle East thought. In one class, his students kept talking about how they wanted to bomb someone. He explained that fighting terrorism is much more complicated. In another class, his fellow graduate students were fascinated when he introduced the concept of the sovereignty of God — which jihadists believe negates the sovereignty of states.

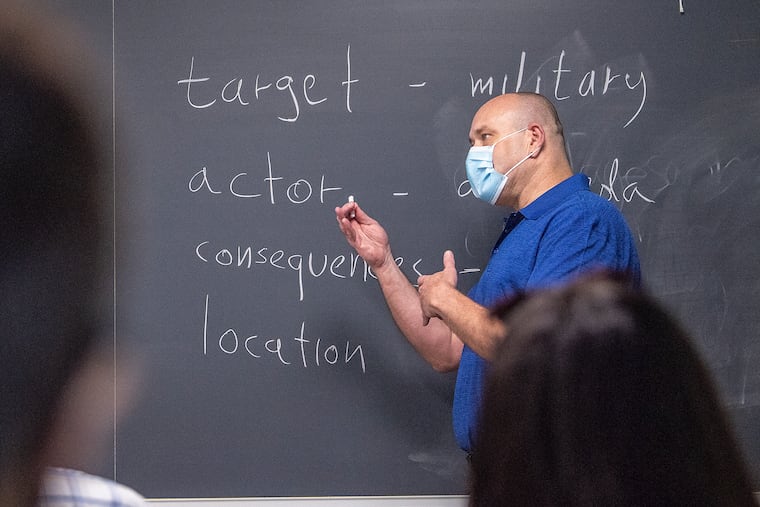

“That ended up becoming the subject of my dissertation and moved to become my first book and the rest of my career,” said Mendelsohn, 49, now an associate professor of political science at Haverford College, where he teaches students about terrorism and national security. “But it was all from ideas I started developing on that same day. Suddenly, I had a role to play. I knew a region that few did.”

Born in a little town outside of Tel Aviv, Mendelsohn grew up, like many children in Israel, fearing violence. His recurring nightmares were those of fleeing Nazis and jumping from trains en route to concentration camps. He still has them, though not as frequently.

He got his bachelor’s degree in Middle East studies at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, then was an intelligence analyst for nearly five years for the Israel Defense Forces. He got his master’s in security studies in Tel Aviv before moving to Cornell in the summer of 2000. An expert in the jihadi movement and al-Qaeda, he started teaching at Haverford in 2007.

What yields strong vivid recollections for older Americans is history for most of his students.

During a class on terrorism studies last week, he asked students to weigh in on whether they thought certain acts, including the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and a fictional bombing of an oil pipeline by environmental activists, qualified as terrorism. While all but one student thought the Jan. 6 attacks were terrorism, students were more split on the oil pipeline attack. One said she would be inclined to side with the environmental activists but still thought it was a form of terrorism.

“It’s to show how values shape who we are inclined to see as terrorists,” he explained. “That demonstrates why we need more objective tools to study terrorism.”

Many mistakes, including the invasion of Iraq and the length of the war in Afghanistan, were made in 9/11′s aftermath, he said.

“Overall, everybody lost,” he said. “Hopefully, 20 years after 9/11, we have a better perspective of what we can actually achieve, what are adverse consequences of actions we may take. Hopefully, we learned something.”

Angry, but not fearful

Stephen Kozol was teaching U.S. history 20 years ago when a colleague knocked on his classroom door at Upper Merion High School and told him to turn on the TV.

Students in his class were distraught, but Kozol no longer expects as visceral a reaction when he teaches about the Sept. 11 attacks.

“In the early years, there was a lot of fear,” said Kozol, 60, who still teaches U.S. history and leads the history department at Upper Merion. “No one knew if this was the first of many such attacks..”

Now, “if you ask a student objectively and you give them the facts — what happened, when it happened, how many casualties there were — they’re horrified by it,” Kozol said. “They’re frequently angered by it. But you don’t encounter them being afraid it could happen again.”

To broach the topic of the terror attacks — an event older than any of his students — teachers need to establish a common understanding of the event, Kozol said.

“When we were first having this discussion, students knew what had happened. They knew the motivations, the people involved. They knew what al-Qaeda was, who Osama bin Laden was. Many students [now] don’t know who Osama bin Laden was until you tell them.”

It’s hard to say when the shift happened. Kozol thinks about other events over the course of his teaching career where he has seen immediate awareness fade: the 1979 oil crisis, the 1986 Challenger explosion.

He’s realized that to help students understand what happened, it’s important to also teach about the immediate reaction.

”You want to do your best to have them feel what you felt,” he said. “Then you can see students starting to relate.”

‘I don’t want it to be dismissed or forgotten’

Joe Martin, the principal of Rancocas Valley Regional High School, knows that stories about how people’s lives were affected by 9/11 will help students understand its significance.

So he and the school’s media coordinator helped produce a 30-minute video that will be shown to about 2,100 students in grades 9 through 12 in their classrooms Friday in which staff members — about half its 150 teachers were elementary students in 2001 — talk about where they were and how they felt when the attacks occurred. The video is interspersed with the unfolding news coverage of the attacks.

“You will see emotion, sadness, anger, and anxiety,” Martin said, but also themes around unity and patriotism.

» READ MORE: Twenty years in the making, Shanksville's Remember Me Rose Garden is built on faith

Two days before his birthday, Martin, now 50, had been teaching a Spanish class when word came about the first attack. A teacher knocked on his classroom door and asked: “Did you hear about the World Trade Center? There’s something weird going on.”

“For the love of God, this happened in our own backyard,” said Martin.

Kristi Maurer, an industrial arts teacher at Rancocas Valley, had just completed teaching a first-period mechanical drawing class at Sterling Regional High School in Somerdale when the attacks occurred, and heard someone say, “We’re under attack.”

A fourth-year teacher, Maurer, then 26, had to reassure students who needed to hear that everything would be fine, when she herself wasn’t sure. She hugged them and spent the remainder of the school day letting students talk and trying to answer their questions.

The school day at Rancocas will begin Friday with a moment of silence at 8:46 a.m., when the first plane hit in New York. Students will be asked to share what they learned with family members over the weekend and get their perspectives of that day, Martin said. He likened the assignment to conversations with his own parents about their whereabouts on the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“I don’t want it to be dismissed or forgotten,” said Martin.