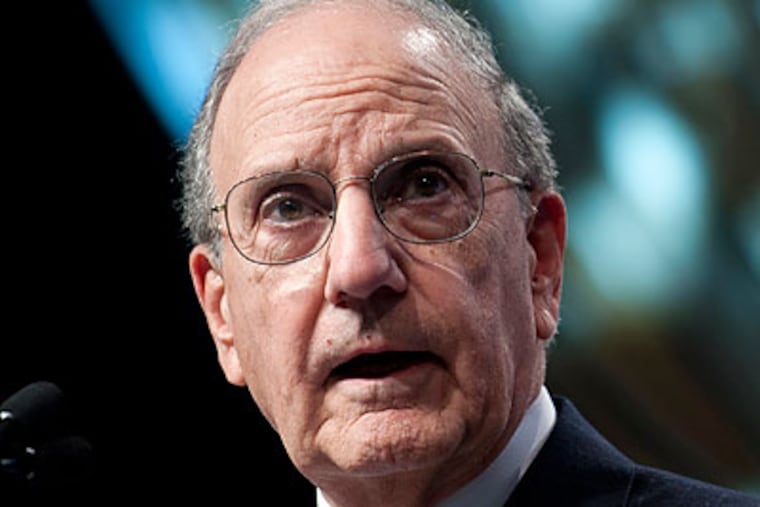

Ex-U.S. senator accused in Jeffrey Epstein scandal oversaw Philly Archdiocese’s sex-abuse compensation fund

George Mitchell, a former U.S. senator, has forcefully denied the claims. But Mitchell’s ties to Epstein have only deepened reservations among Philadelphia-area clergy sex abuse victims about a program many of them already viewed with skepticism.

Among the prominent men accused of sexual abuse in a cache of recently unsealed court documents tied to financier Jeffrey Epstein’s alleged trafficking of underage girls, one name stood out to clergy sex-abuse victims in Philadelphia: George J. Mitchell.

Better known for his stints as a Senate majority leader and a U.S. special envoy, Mitchell until May had led the board overseeing the Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s compensation fund for those abused by priests.

Although he has forcefully denied the claims and his accuser has offered few details of their alleged encounter, the news has drawn consternation and bewilderment from Philadelphia-area victims and their advocates.

Some simply smirked at the optics that the man handpicked to oversee the archdiocese’s most significant attempt to date to compensate abuse victims had himself been accused as an abuser. Others said that Mitchell’s ties to Epstein have only deepened their reservations about the church’s reparations process — a program many of them already viewed with skepticism.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all,” said John Delaney, who has alleged his childhood priest raped him when was a 12-year-old altar boy at St. Cecelia Parish in Northeast Philadelphia and who rejected a compensation offer from the fund. “It definitely calls into question the entire effort, if [Mitchell] did this.”

But Ken Gavin, a spokesperson for the archdiocese, said that church officials remain grateful for Mitchell’s guidance and cited the more than $19.6 million the Philadelphia compensation fund gave to more than 79 abuse victims between November and May.

“The senator’s efforts always focused on how to help heal victims,” Gavin wrote in an email. “Senator Mitchell and the other two distinguished members of the oversight committee have done remarkable work.”

‘My body was put on the banquet menu’

Mitchell, citing new work commitments at his law firm, DLA Piper, stepped down in May from the oversight committee of the archdiocese’s Independent Reconciliation and Reparations Program (IRRP).

In a statement Aug. 11, Mitchell maintained he has never met Virginia Giuffre — the Epstein accuser who had listed him among her many alleged abusers along with a host of other boldface names including former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson; lawyer Alan Dershowitz; and Prince Andrew, son of Queen Elizabeth II.

“My body was put on the banquet menu … for a powerful senator, George Mitchell, and another prominent Nobel Prize winning scientist,” Giuffre wrote in an account of the years she allegedly spent as a self-described teen sex slave for Epstein and his powerful friends. “They would be only some of the recognizable figures of the high society that became added to my list of clientele.”

That unpublished manuscript had remained under court seal for years after it was submitted as evidence in a 2015 defamation suit Giuffre filed against Ghislaine Maxwell, a British socialite and onetime partner of Epstein’s whom federal authorities are said to be investigating in the days since the financier hanged himself in his New York prison cell Aug. 10.

That document and others included as part of Giuffre’s case were released earlier this month by the New York-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Giuffre mentioned Mitchell again in a sworn deposition in 2016, saying she was instructed to give him a sexual massage while the former senator was visiting Epstein in Palm Beach, Fla.

Mitchell, in his statement, dismissed her claims.

“I have never met, spoken with, or had any contact with Ms. Giuffre,” the senator said. “In my contacts with Mr. Epstein, I never observed or suspected any inappropriate conduct with underage girls. I only learned about his actions when they were reported in the media related to his prosecution in Florida. We have had no further contact.”

‘An outstanding job’

Mitchell has not been charged with a crime, Giuffre’s claims have not been tested in court, and there has been no indication that the senator has become a target of the ongoing federal investigation.

Still, the archdiocese’s compensation program should address the issue head-on and seek to reassure sex-abuse victims that the allegations have no bearing on the program, said Laura Otten, an expert in nonprofit management at La Salle University.

“They have to get out in front of it and distance themselves from this, while at the same time making it clear that they like everyone else are waiting for an investigation to complete its work,” she said.

Giuffre’s allegations against Mitchell were not known when Philadelphia Archbishop Charles J. Chaput appointed him to lead the committee overseeing the IRRP in November. But his friendship with Epstein — then a convicted sex offender after a 2008 plea deal in Florida — was well-documented.

Mitchell called Epstein a “friend and supporter” in a 2003 New York Magazine profile. Epstein referred to Mitchell as the world’s greatest negotiator.

As chairman of the independent oversight committee last year, Mitchell and other members were tasked with drafting protocols and policies for the compensation program and with monitoring the claims process. The determination of payouts to individual claimants is handled by fund administrators Kenneth Feinberg and Camille Biros.

Many who worked with the former senator on the compensation fund have been reluctant to discuss Giuffre’s allegations or the impact they might have on its work. Oversight committee members Kelley B. Hodge, a former Philadelphia district attorney, and Charles Scheeler, Mitchell’s former law partner, did not return requests for comment.

Lawrence F. Stengel, the retired federal judge from Lancaster who has taken over Mitchell’s role as committee chairman, said he thought the senator had done “an outstanding job.”

“I certainly wasn’t aware of any allegations,” Stengel said. “I don’t think anything like that factored into or filtered into the IRRP. He expressed concern for victims and victim advocates. He was very invested in the integrity of the process.”

‘More of the same’

The fund itself has divided abuse victims, some of whom see the effort as an attempt by the church to short-circuit efforts in the state legislature to pass a law that would allow accusers to sue for abuse that falls outside the current statute of limitations.

Since the fund’s launch last year, more than 197 accusers have filed claims. Nearly 80 cases had received final determinations as of spring with an average payout of more than $210,000, according to the program’s reporting through May.

Those who are granted and accept awards must agree not to sue if the state’s laws change, as happened recently in New York and New Jersey.

Jordan K. Merson, an attorney who represents several clients seeking payments from the fund, said that trade-off has worked well for some of them — including victims who are older, ones who need money for therapy or counseling services, or those whose primary goal was simply getting the church to acknowledge their abuse.

“But for people who have had their lives ruined by their experiences or been subjected to serious acts of abuse, the program cannot and does not provide the necessary compensation,” Merson said. “I’ve had some people go through the program and be very happy, and I’ve had some that aren’t so happy.”

As for the allegations against Mitchell, lawyer Daniel F. Monahan said, most of his clients remain unfazed. Given the suspicion many of them still harbor toward the church since their abuse, he said, “a lot of them would say it’s just more of the same.”