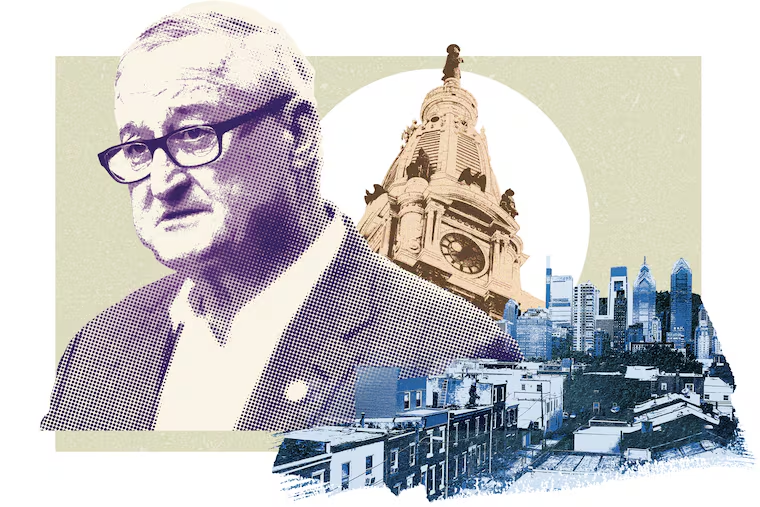

Mayor Jim Kenney wants to be remembered as ‘someone who cared’ — even if he didn’t always seem like it

Kenney admits the pandemic and upheavals of his second term have changed him and have had profound impact on his mental and physical health. But he told The Inquirer he's not sorry he did the job.

Mayor Jim Kenney gave hundreds of speeches during his eight years in office. But fairly or not, the 11 words for which he is most likely to be remembered are ones he uttered while standing on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway on the night of July 4, 2022:

“I’ll be happy when I’m not here — when I’m not mayor.”

For Kenney, it was a moment of exasperation after two police officers were struck by stray bullets. But for many Philadelphians, it was the crystallization of a growing frustration about a mayor who didn’t seem to want the job.

As with any mayor, Kenney’s legacy will be defined by the city’s successes and failures during his tenure, from his efforts to improve Philadelphia public schools to the record-setting levels of shootings and homicides.

But more than any of his recent predecessors, he will also be remembered for his temperament. Kenney, 65, often appeared sullen when many were looking for resolve, and he had a hands-off leadership style — qualities that were magnified by a time of crisis.

He admits that the pandemic and the upheavals of his second term have changed him, and that the job has had a profound impact on his mental and physical health. But he said he is not sorry he did the job, and he knows how he wants to be remembered: “as someone who cared.”

In a recent interview in a City Hall conference room, Kenney noted that he’s acknowledged his mistakes. He has apologized, for instance, that the city entrusted a 22-year-old to manage COVID-19 vaccination. He apologized that officers blanketed parts of the city in tear gas in 2020, “a lowlight” of his eight years in office. He even called a special news conference just to apologize for saying he’d be happy when he’s not mayor.

And he defended himself against critics who have called him disengaged, saying they couldn’t see how the job affected him.

They weren’t with Kenney in the early days of the pandemic when he thought the world might be ending, but had to project that things were under control. They weren’t there during the 2020 protests, when Kenney was with police looking at six screens showing different parts of the city — all on fire.

And they didn’t see the things he has seen over the last three years that make him choke up to this day. The floor of a basketball arena made into a hospital. The firefighters weeping on stoops before they brought out the bodies of children killed in a catastrophic blaze. The look on the face of a police officer’s wife when she was told that her husband was never coming home.

“They don’t have a clue,” Kenney said of his detractors. “Sometimes I lay in the bed at night and look at the ceiling and I can’t fall asleep because we had a triple shooting, a triple homicide, that night. And I’ve internalized it much to my detriment.”

He added: “I’ll get better when I’m out of it and I’m not thinking about or waiting for a bad phone call.”

For Kenney, the gloomy demeanor people saw was not a reflection of his disengagement, but rather of the fact that he cared — about children, city workers, and immigrants, especially.

It may be difficult to convince people of that with weeks to go in his tenure — and his handling of the interview was emblematic of the communication difficulties that have defined perceptions about his tenure. He has rarely in his second term granted extended interviews to local media, and he began the conversation by saying he was only interested in discussing policy, not “subjective stuff about feelings and emotions.”

He then proceeded to open up for an hour about the emotional impact the pandemic and the gun violence crisis has had on him, tearing up several times in moments that would have made it difficult for anybody to doubt he cared about the job — if they could see it.

The fights Kenney relished

Kenney was never much of a cheerleader type.

The son of a firefighter from Third and Cantrell Streets in South Philly, Kenney began his political life in 1978, when he started doing odd jobs for then State Sen. Vince Fumo. He was just 32 when he was elected to his first term as an at-large member of Council in 1991.

Kenney was known in Council as a labor-friendly Democrat with a progressive streak who operated with candor. He’s Catholic, but feuded with the church over gay rights. He was a driving force behind decriminalizing marijuana possession. He supported former Mayor Michael Nutter, but when their relationship soured, Kenney said in 2013: “[Nutter] doesn’t communicate. He goes his own way, and he doesn’t build coalitions.”

And he was known for mean, absurd, and morose tweets, like one directed at former N.J. Gov. Chris Christie that said, “You suck!” and another that merely read: “So sad sometimes.”

In early 2015, Kenney entered the race for mayor late and somewhat hesitantly, jumping in at the urging of labor unions only after it was clear that Council President Darrell Clarke would not run. He won the Democratic primary resoundingly by building a unique coalition involving labor, Black ward leaders, progressives, and working-class white voters.

“I want a lot of things for our children,” he said in his victory speech, “but, most of all, I want them to grow up in a Philadelphia where we all look past our differences and join together to create a better place for all of us to live.”

The mood among supporters was “electric,” said Cynthia Figueroa, who led the Department of Human Services in Kenney’s first term and was later the deputy mayor for children and families.

“And it’s kind of sad, because I feel like there’s a lot that people that don’t remember, because the second term was so mired in challenges and that sort of sense of giving up,” she said. “But the first was so highly energized.”

In his very first budget proposal to Council, Kenney unveiled what has turned out to be by far his most significant policy accomplishment: a new tax on sweetened beverages.

Nutter had twice tried and failed to get Council to pass a so-called “soda tax.” But Kenney got it done — and overcame a massive lobbying effort — thanks to his relatively strong relationships with lawmakers and by emphasizing the programs the tax could fund: expanded high-quality pre-K, recreation centers renovations, and “community schools” that provide social services.

Council approved the tax in a 13-4 vote in June 2016. Just six months into his tenure, the biggest legislative fight of his administration was over.

Kenney now frequently visits recreation centers, libraries, and preschools to tout those wins. He said that, to this day, he feels most comfortable in those tiny chairs meant for 4-year-olds, where, for a moment, the realities of the adult world melt away.

Kenney was perhaps most visibly energetic when he was defending Philadelphians against the policies of then-President Donald Trump.

After Kenney’s administration in 2018 won a court case allowing it to remain a “sanctuary city” for undocumented immigrants, a video of Kenney dancing and high-fiving in celebration went viral, and a Trump spokesperson called it “disgusting.”

The mayor said the decision “prevents a White House run by a bully from bullying Philadelphia into changing its policies.”

It was a fight he relished.

A second term begins before ‘Armageddon’

By the time his first term had come to a close, Kenney had largely avoided major scandals.

His police commissioner, Richard Ross, resigned in 2019 after a lawsuit claimed he ignored a complaint of sexual harassment lodged by a subordinate with whom he’d had an affair. And Kenney’s main political benefactor, building trades union leader John J. Dougherty, had been indicted on corruption charges.

But the mayor emerged from those episodes largely unscathed and cruised to reelection.

In a recent interview, Clarke recalled that at the start of Kenney’s second term, in January 2020, things were looking up. The mayor had named a new police commissioner, Danielle Outlaw, the first Black woman to ever hold the job. Thousands of children were in pre-K, the administration was launching a major scholarship program, and projects to renovate rec centers were underway.

Then, 64 days after Kenney started his second term, Philadelphia reported detecting the city’s first case of COVID-19.

“Then we got this call saying, ‘Yo, this thing is real, you guys got to shut it down,’” Clarke said.

Kenney recalled that the early days were chaotic, and that there was no playbook — no former mayor he could call for advice.

“Armageddon,” he said.

Kenney’s behind-the-scenes tendencies weren’t as well suited for the pandemic, when residents craved comfort, said Nina Ahmad, an incoming Council member who served for two years as a deputy mayor under Kenney.

“Jim is not a touchy, feely, happy, smiley guy. He’s always got a serious demeanor,” she said. “He cares about people and things; he’s just not a very outgoing person. He’s much more, like, ‘Can we get the work done?’”

‘A two-front war’ in a time of crisis

Some of Kenney’s top aides noticed that his second term had fewer of what they called “glasses-off” moments — humanizing points at the end of speeches when he’d remove his glasses, look at the audience, and speak from the heart.

But through the pandemic, he more often stuck to script in monotone or simply passed the mic to someone else. And he pursued no major policy initiatives.

Mike DiBerardinis, who served as managing director during Kenney’s first term, said it was understandable that Kenney would limit his ambitions in a time of crisis.

“In times of crisis all leaders have a tendency to shrink your game and limit casualties and don’t take any chances,” he said. “You’re in a two-front war. You’re trying to manage. And what do you have left in terms of political clout and money to advance that agenda?”

But the mayor could have done more, he said, to “open up more and to engage more and to shape the politics and the perceptions of your constituents.”

“You’ve got to extend yourself, and you’ve got to bring people along,” DiBerardinis said. “You have to think bigger than what the circumstances are suggesting.”

Kenney is a well-known delegator and has always empowered his top deputies to lead strategy for their own departments. That approach appears to have worked well until crisis struck, when it contributed to a feeling that Kenney wasn’t managing the situation.

The tear-gassing on I-676 and a botched vaccination contract with Philly Fighting COVID were decisions made by Kenney’s underlings, not him. And he often allows subordinates to be front and center at moments when other politicians would seize the spotlight, such as the administration’s daily briefings during the early days of the pandemic.

But when things went awry, it was still Kenney who had to defend the administration.

For example, the police department’s handling of the 2020 racial justice protests was widely panned as disorganized and heavy-handed. Kenney didn’t specifically green-light officers to use tear gas on protesters trapped on an I-676 embankment, but he at first defended its use and stood by his police commissioner.

They both later apologized. Today, he says, “I own it.”

Historic homicide rates and criticism from every corner

Another crisis exploded — one that perhaps did more damage to the city’s morale than the pandemic.

Rates of shootings and homicides skyrocketed in 2020, and by the end of that year, 454 people were dead. More carnage followed, and nearly 1,500 people were killed in three years — the deadliest stretch in modern city history.

There were high rates of carjackings, auto thefts, and illegal gun possession, and public safety became most residents’ top concern.

But city leaders weren’t projecting unity, and many blamed Kenney. He and Outlaw outwardly contradicted progressive District Attorney Larry Krasner about which crimes police should prioritize, and Council members, including some of Kenney’s allies, were critical of the administration’s response, saying that it lacked urgency.

Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, of West Philadelphia, publicly called on Kenney to declare a state of emergency — to no avail — and then-City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart, who later ran for mayor, said other cities were doing more to stem the bloodshed. Activists called for Kenney to resign, saying he wasn’t outraged enough.

Kenney made clear he thought that he was unfairly blamed by critics and the media. He noted that gun violence was up across the country, and that his administration spent more than half a billion dollars on initiatives outside traditional policing aimed at curbing violence.

He still says the violence was the result of lax state and federal gun laws, record-high firearm sales during the pandemic, and a mental-health crisis caused by the upheaval.

“I’m not blaming that. Look, it’s our responsibility,” Kenney said. “It’s not our fault. It’s our responsibility. And we’re taking responsibility and moving those numbers down.”

The homicide rate has fallen significantly this year. But while killings are down 19% compared to the same point last year, the nearly 400 homicides so far this year are still more than in any year between 2008 and 2020.

Kenney said he knows gun violence will be part of his legacy — but he isn’t concerned about how history will look at him.

“What bothers me is that all those families lost all those people,” he said, eyes welling with tears. “I will be a memory at some point. A distant memory. They will live with that forever.”

Where the mayor goes from here

Jan. 1 will be the first time in more than 30 years that Kenney will be a private citizen. He said he doesn’t have a new job lined up.

“It’s a big change,” he said. “I’m watching stuff coming off the walls. People are starting to pack up; people are leaving the administration. It’s a life change. But it’s fine. It’s inevitable.”

He demurred when asked if he’s planning a wedding with fiancée Letitia Santarelli. He said he won’t be returning to social media, which he said “empowers cowards” and “distorts truth.”

Kenney does plan to travel — high on his list is Lisbon, Portugal. Kenney loves European cities and, despite his fondness for Madrid — “one of the finest cities I’ve ever been in” — he has no plans to move there, as was rumored. He said he intends to live in Philadelphia.

Whatever he does with his time, he said he hopes to be working with children, whom he much prefers to adults. During the interview, Kenney shared a quote he said came from an Irish poet.

“People are all born perfect,” he said. “And then they learn to speak.”