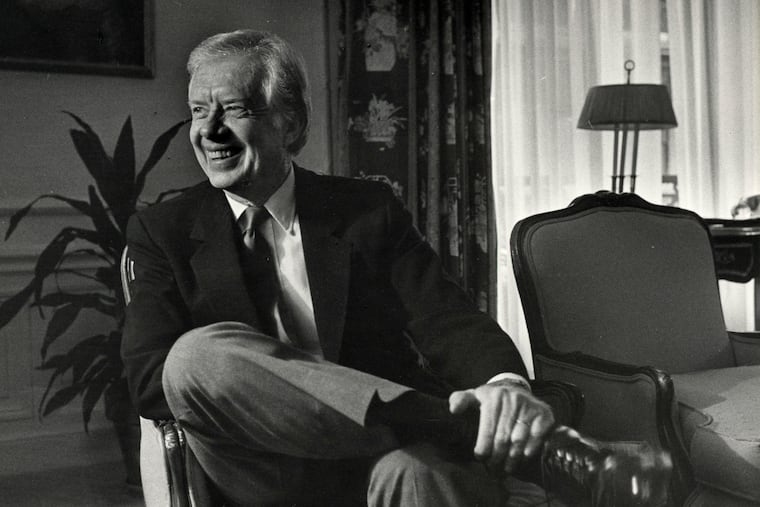

Jimmy Carter, tireless humanitarian admired as model ex-president, has died at 100

He taught Sunday school, pounded nails with Habitat for Humanity, brokered international peace deals, and won a Nobel Prize during a life he called “an exciting, adventurous, gratifying existence.”

Jimmy Carter, 100, the peanut farmer who became the commander in chief, whose ceaseless humanitarian work around the globe superseded his one tumultuous term as 39th president of the United States, died Sunday, Dec. 29, in hospice care at his longtime home in Plains, Ga., according to his nonprofit organization.

Born Oct. 1, 1924, Mr. Carter died a little more than a year after his beloved wife, Rosalynn, who died on Nov. 19, 2023, at 96. He lived longer than any other U.S. president, surpassing George H.W. Bush, who died in 2018 at 94. He endured melanoma skin cancer that spread to his liver and brain in 2015, underwent brain surgery in 2019 after a fall, and had returned to his ranch house in Plains in February 2023 after a series of short hospital stays.

Still, up until 2015, Mr. Carter continued to teach Sunday school classes, work on Habitat for Humanity building projects, lecture at Emory University in Atlanta, and flash those bright blue eyes at ribbon cuttings, book signings, and other public events.

“I’m perfectly at ease with whatever comes,” he said in 2015 when his health began to decline. “I’ve had a wonderful life. I’ve had thousands of friends. I’ve had an exciting, adventurous, gratifying existence.”

When news of Mr. Carter’s move to hospice care first circulated on Feb. 18, 2023, admirers flocked to his boyhood home in Plains and the Carter Center in Atlanta, and tributes poured in from world leaders, American politicians, social activists, journalists, and everyday citizens across the globe.

Former President Bill Clinton tweeted an old photo showing him and Mr. Carter sitting together, smiling and chatting. U.S. Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr. of New Jersey tweeted: “Jimmy Carter is the model of kindness, generosity, and decency that is the finest part of America.”

Word of his death late Sunday afternoon brought swift and heartfelt reactions from elected officials.

President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden called Mr. Carter “an extraordinary leader, statesman and humanitarian. ... What’s extraordinary about Jimmy Carter, though, is that millions of people throughout America and the world who never met him thought of him as a dear friend as well.”

In a statement on Truth Social, President-elect Donald Trump said Mr. Carter, as president, “did everything in his power to improve the lives of all Americans. For that, we all owe him a debt of gratitude.”

On X, formerly Twitter, former President Barack Obama said Mr. Carter ”taught all of us what it means to live a life of grace, dignity, justice and service.”

In a joint statement, former President Bill Clinton and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton praised Mr. Carter for having “worked tirelessly for a better, fairer world.

Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro ordered flags at half-staff throughout the commonwealth, and remembered Mr. Carter on X as ”a humble, generous, and admirable public servant — both as our President and in his years after as a citizen in service.”

“We pray that, in rest, President Carter will be reunited with his beloved wife Rosalynn,” New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy said in a statement on X.

Calling Mr. Carter “one of the foremost advocates of affordable housing in this country,” Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle L. Parker took to X to recall a visit by him to North Philadelphia to help build homes with Habitat for Humanity “that are still in use today.”

» READ MORE: How Jimmy Carter helped build 4,390 homes with Habitat for Humanity

Mr. Carter, a Democrat, served a single, turbulent term in the White House from 1977 to 1981, and it is largely for his efforts after leaving office that he will be remembered. He constructed homes for Habitat for Humanity, wrote dozens of books sharing his own life details, shared advice on health and diet, and guided the Carter Center toward at least one remarkable public health breakthrough in Asia and Africa.

A man of profound faith and optimism, Mr. Carter remained sanguine about the future despite constant conflict among religious groups. “I am convinced that Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, and others can embrace each other in a common effort to alleviate suffering and to espouse peace,” Mr. Carter said in Oslo, Norway, on Dec. 10, 2002, as he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize.

Mr. Carter surprised political pundits when he emerged from small-town Georgia to win the White House in 1976. He was the only Democratic president during a 24-year period in which Republican chief executives were the rule. A relative unknown before attaining the presidency, he was considered an outsider, even in his own party.

The singular achievement of his years in power was his role in negotiating a milestone peace agreement between Egypt and Israel, longtime rivals in the Middle East.

But to millions of Americans, Mr. Carter, who once vowed to make government “as good and as decent as the American people,” seemed overwhelmed by the job. He had the misfortune to serve in stormy times and, in the eyes of his critics, came to embody ineptitude at home and weakness abroad.

His four years in office are remembered most for the traumas that played out in his last year. Fifty-two Americans spent 444 days, from Nov. 4, 1979, to Jan. 20, 1981, held hostage in Iran while the U.S. economy faltered under the highest inflation and interest rates in a generation.

The year culminated when voters went to the polls in November and gave Mr. Carter one of the most resounding votes of no-confidence ever dealt an incumbent president. And the Iranians delivered the final insult, refusing to end the hostages’ imprisonment until a half hour after he left office and Ronald Reagan was sworn in.

“That was the image that I left behind in the White House,” Mr. Carter recalled later, “that I was not strong enough or not macho enough to take military action to bring these hostages home.”

Asked in 2015 if he wished he had done anything differently, Mr. Carter did not grandstand. He drew laughs by saying he wished he had sent “one more helicopter” on the botched attempt in 1980 to rescue the hostages. “We would have rescued them, and I would have been reelected,” said Mr. Carter, flashing his famous toothy grin.

For all of his troubles in office, he earned renewed respect in his post-White House years for his intelligence, integrity, and commitment to peace and human rights. He was frequently said to be a model ex-president.

» READ MORE: How cowriting a book threatened Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter’s marriage

Unlike some other former chief executives, he did not spend his time playing golf or selling his services as a public speaker or a private consultant. Instead, he took tools in hand and built homes for the needy in the United States and villages in Africa and Latin America.

And through the work of the Carter Center, he devoted himself to resolving conflicts, promoting democracy, and combating health problems throughout the world.

He was proud of the Carter Center’s success in helping to eradicate the debilitating illness known as Guinea worm. In 1986, when the Carter Center began its efforts against the disease, its officials said there were an estimated 3.5 million cases occurring annually in Africa and Asia. The center said the incidence of Guinea worm fell to 28 cases in 2018.

“I’d like for the last Guinea worm to die before I do,” Mr. Carter said in 2015.

A humble start

James Earl Carter Jr. was born in the town of Plains, Ga., population 550. His ties to the barren landscape of southwest Georgia were deep and lasting. He spent most of his adult life in his birthplace, living in Plains from 1953 until his death, except for the years he spent in executive mansions in Atlanta and Washington.

Actually, Mr. Carter grew up three miles west of Plains, in the unincorporated hamlet of Archery, in a clapboard farmhouse alongside a dirt road. But it was in Plains that he attended school and church and sold boiled peanuts on the street.

His father, James Earl Carter, known as Mr. Earl, was a stocky, conservative authority figure. His mother, Lillian Gordy Carter, known as Miss Lillian, was something of a rebel, a liberal with a curious mind and training as a registered nurse.

As he came of age, Mr. Carter’s goal was to attend the U.S. Naval Academy. He got there in 1943, graduating 59th in a class of 820, and going on to work with the unit that developed the first nuclear submarine.

But, after the death of his father, he left the Navy and brought his wife, the former Rosalynn Smith, and their three sons, Jack, Chip, and Jeff, home to Plains to run the peanut-growing and farm-supply business.

In 1962, at 37, Mr. Carter entered politics, winning a seat in the Georgia State Senate. Four years later, he ran for governor and lost in the Democratic primary. The defeat sent him into a deep funk, causing him to question the entire direction of his life.

He resolved his self-doubts by becoming born-again, spending much of the next year working as a lay missionary. The experience left him with a renewed commitment to become governor.

In 1970, he won the job and, upon being inaugurated, declared: “The time for racial discrimination is over.” He ordered that a portrait of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. be hung in the state Capitol, a move that won him the undying affection and political support of Dr. King’s widow and father.

His public statements and symbolic acts won him considerable publicity, and he was seen as one of a new breed of politicians from the New South. Perhaps the most important thing that happened to Mr. Carter as governor was that he invited politicians from around the country to stay at the governor’s mansion when they were in Atlanta.

They did not impress him. He figured he was as talented as any of them. If some of them could run for president, he asked, why couldn’t he? So, in 1976, he did.

And, as the election year approached, events broke his way. The Watergate scandal forced Richard M. Nixon to resign the presidency in disgrace in 1974, leaving the office to the unelected Gerald R. Ford.

All that did severe damage to the Republican Party and federal establishment, setting the stage for someone like Mr. Carter, a Democrat who came from the outside talking about decency and morality. He was the first real long shot to prevail in the age of media politics, the first man to demonstrate how to get elected by running full-time for two years.

Speaking softly but with a missionary’s zeal, Mr. Carter promised voters that he would “never tell a lie.” He was liberal on civil rights, conservative on economics, and hard to categorize on almost everything else.

When he accepted the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination at its convention in New York, he had a lead of more than 30 points in the polls over President Gerald Ford. In the end, he won narrowly, getting 51% of the vote to Ford’s 48%, 297 electoral votes to Ford’s 241.

On Inauguration Day 1977, Mr. Carter reinforced his image as the humble outsider in an unforgettable way. After being sworn in on the Capitol steps, Mr. Carter, his wife, and young daughter, Amy, got into a limousine for the traditional ride down the parade route to the White House. Then, despite the bitter cold, the three of them climbed out and walked the rest of the way.

The idea, he said, was to show that the “imperial presidency” of the Nixon era was dead and gone. “It was,” he wrote later, “one of those few perfect moments in life when everything seems absolutely right.”

Tough times

There were few more moments like that in the Carter administration. Even though the Democrats held overwhelming majorities in both houses, he found it hard to get things done.

His proposals for welfare, tax reform, and a national health program all disappeared without a trace. His attempt to get the government to adopt a national energy policy — an effort he described as “the moral equivalent of war” — did not fare much better.

Inflation crippled the economy, and frayed relations between the White House and Congress crippled the government. So he turned his attention to foreign affairs.

First came Panama. For several years before Mr. Carter took office, the United States had been negotiating about the future of the U.S.-built Panama Canal, the vital waterway linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Mr. Carter completed the negotiations. Under the final agreement, the canal would be turned over to Panama in 1999, although the U.S. retained the right to use force to keep the canal open. After a bruising, yearlong battle, the Senate ratified the treaty.

Then came the Middle East. No other foreign policy area so absorbed him. Indeed, few presidents in the 20th century were so consumed with trying to bring peace to the Holy Land.

Almost immediately after taking office, Mr. Carter began meeting frequently with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Progress seemed possible when Sadat, on Nov. 19, 1977, took the risky and unexpected step of traveling to Jerusalem, the Israeli capital, to address the Israeli parliament.

But the inability of Egypt and Israel to convert the opening into a peace agreement left Mr. Carter ever more frustrated. “There was only one thing to do, as dismal and unpleasant as the prospect seemed,” he later recalled. “I would try to bring Sadat and Begin together for an extensive negotiating session with me.”

On Sept. 5, 1978, Mr. Carter, Sadat, Begin, and their staffs gathered at Camp David, the presidential retreat in the Maryland mountains, and shut themselves off from the world. For Mr. Carter, as host and mediator, the stay at Camp David would prove to be the highlight of his presidency.

On Sept. 17, an agreement was reached on a framework for peace. Egypt would recognize Israel’s right to exist. In return, Israel would withdraw from the Egyptian territory in the Sinai it had occupied since the Six Day War of 1967.

That night, in the East Room of the White House, the three world leaders signed that framework. Six months later, the framework blossomed into a full-fledged peace treaty.

While the Camp David process resulted in peace between Israel and Egypt, it did not produce significant progress toward peace throughout the region. That became a source of increasing disappointment to Mr. Carter after he left office.

Nor did Mr. Carter achieve any major breakthroughs in U.S.-Soviet relations. The two nations negotiated a second Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, SALT II, which Mr. Carter and Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev signed on June 18, 1979, at a summit meeting in Vienna. But the pact did not call for cuts in nuclear arsenals, only ceilings.

Opposition to the treaty sprang up in the Senate almost immediately. Whatever chance it had of ratification expired at the end of that year, when Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan.

Mr. Carter reacted to the Soviet invasion by imposing an embargo on American grain sales to the Soviet Union and by having the United States boycott the 1980 Summer Olympic Games, which were set for Moscow. By then, his presidency was in deep political trouble.

These were unsettling times in America. Gasoline prices were high, and lines at fuel pumps were long. Inflation and unemployment were rising. So, too, was national pessimism.

Awareness of that pessimism had caused Mr. Carter to retreat to Camp David in July 1979 for an extended, loosely structured domestic summit. When it was over, he delivered a nationally televised speech on what ailed the nation and then fired three members of his cabinet. The episode came to be known as the “malaise speech.”

Mr. Carter seemed, in the view of his critics, to be trying to shift the blame for the nation’s problems away from his administration and onto the American people. He seemed to be confessing his impotence.

Within days, there was a large and growing body of thought in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party that Sen. Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts should challenge Mr. Carter in the 1980 presidential primaries. Kennedy did run. But by the time he announced his candidacy, the political landscape had been transformed.

On Nov. 4, 1979, in the Iranian capital of Tehran, about 3,000 militants loyal to Iran’s new revolutionary leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, overran the U.S. Embassy. They denounced America as “the Great Satan.” And they took hostages.

The number of hostages would vary in the long days ahead. Ultimately it would settle at 52. Thus began, Mr. Carter recalled later, “the most difficult period of my life.”

It was not just 52 individuals who were held captive. It was an entire nation. The episode crystallized the general sense that U.S. power and prestige had deteriorated.

At first, the crisis worked to Mr. Carter’s political benefit. Americans rallied around their president, and the prospects of his two main challengers within the Democratic Party, Kennedy and California Gov. Jerry Brown, seemed to flag.

But, as months passed and the hostages remained in captivity, the nation’s patience with Mr. Carter grew thin, as did his own patience with Iran. After months of intensive and fruitless negotiations behind the scenes, the president decided to try to rescue the hostages.

On April 24, 1980, the mission was launched. Success depended largely on eight helicopters, which were to ferry the rescuers from a makeshift base in the Iranian desert to Tehran itself. But two of the helicopters malfunctioned, and one of them crashed into a transport plane in the desert, killing eight servicemen.

The failure of the mission undercut what was left of the nation’s confidence in Mr. Carter. He carried on and was renominated by a deeply divided Democratic Party. The atmosphere on the final night of the convention in New York was so bitter that Kennedy refused to raise Mr. Carter’s hand in the traditional display of party unity.

“The bond of our common humanity is stronger than the divisiveness of our fears and prejudices.”

In the general election campaign, the Republican nominee, former California Gov. Ronald Reagan, sealed Mr. Carter’s defeat by posing to the nation: “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” Many Americans — thinking of the hostages, double-digit inflation, and soaring interest rates — couldn’t help but answer “No.”

In the end, Mr. Carter got only 41% of the vote, to Reagan’s 51% and 7% for independent John Anderson. But there was a landslide in the Electoral College — 489 for Reagan and only 49 for Mr. Carter.

He devoted what remained of his term to getting the hostages out. They were released on Jan. 20, 1981, Inauguration Day.

Never slowing down

After leaving the White House, Mr. Carter went home to Plains. There, he wrote his memoirs and raised the money to build his presidential library in Atlanta. He devoted much of his time and effort to open the Carter Center in 1982.

In the mid-1980s, Mr. Carter staged well-publicized sessions on the Middle East and arms control, both of which were cochaired by Gerald Ford. Mr. Carter described the friendship between the old rivals as “a surprise to both of us.”

As the years passed, Mr. Carter kept pursuing his causes, traveling throughout the Middle East and Latin America to foster democracy and human rights. He became almost universally recognized as an “honest broker” whose word was accepted by one and all.

“It’s possible under some circumstances that I could be more meaningful as a human being this way than if I’d had a second term in the White House,” he said in 1985.

In 1989, he arranged for peace talks between the Ethiopian government and the Eritrean rebels. In 1990, he monitored the elections in Nicaragua. In 1994, he mediated the end of a military coup in Haiti, went to North Korea, and brokered a truce in Bosnia.

His accumulated efforts won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002, the citation praising him for standing by the principles that “conflicts must as far as possible be resolved through mediation and international cooperation based on international law.”

”My father was a hero, not only to me but to everyone who believes in peace, human rights, and unselfish love,” son Chip posted on the Carter Center’s website. “My brothers, sister, and I shared him with the rest of the world through these common beliefs. The world is our family because of the way he brought people together, and we thank you for honoring his memory by continuing to live these shared beliefs.”

In addition to his three sons and daughter, Mr. Carter is survived by 12 grandchildren, 14 great-grandchildren, and other relatives. Two sisters, a brother, and a grandson died earlier.

Services are pending. Biden said Sunday he will be ordering an official state funeral to be held in Washington.

Staff writers Julia Terruso, Michelle Myers and Diane Mastrull contributed to this article.