Did John Wilkes Booth get away with murdering President Abraham Lincoln?

The latest photo-recognition software backs a belief that had been dismissed by most historians as conspiracy nonsense.

The researchers were hot on the trail of an infamous 19th century assassin, using the latest 21st century technology to track him down.

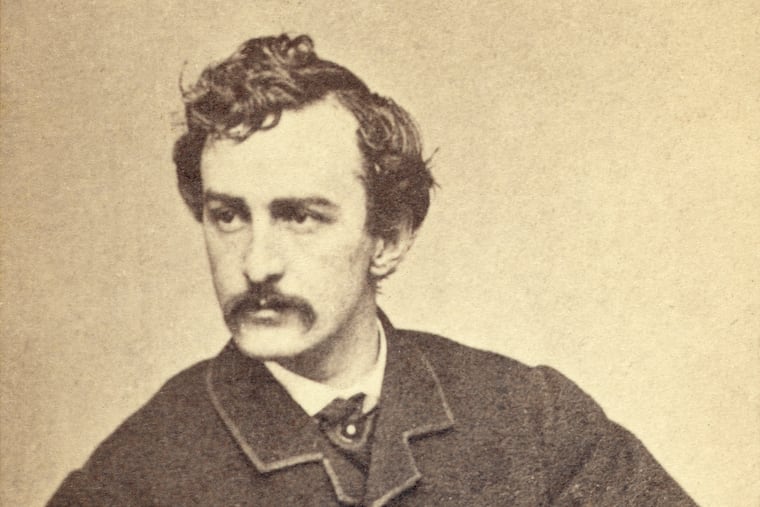

Before them were photographic images of a man named John St. Helen from 1877, of the embalmed corpse of a David E. George from 1903 — and of John Wilkes Booth taken in 1865, shortly before he famously fired a .44-caliber pistol, made by Philadelphia’s Henry Deringer, into the head of President Abraham Lincoln.

Facial-recognition software, already loaded with photos of 5,000 other white males, began to meticulously analyze the faces for similarities: the spaces between the eyes, the jaw lines, the shapes of the noses and cheek bones.

In less than a minute, results came back that left the researchers stunned. The data showed a strong possibility that all three photographs were of the same man — a belief long-held by a small number of historians, but always dismissed by scholars and assassination experts as conspiracy nonsense.

Though not as definitive as DNA results, the facial recognition test used widely by law enforcement agencies raises the prospect on April 15, the 154th anniversary of the day Lincoln died, that Booth was not killed in a Virginia tobacco barn by a Union soldier in 1865, as history books say, but lived 38 years more as St. Helen and George, said Ramy Romany, an author and Egyptologist who helped oversee the Booth investigation as part of the new TV series Mummies Unwrapped.

“I was absolutely shocked,” said Romany, host of the segment scheduled to air on the Discovery Channel at 10 p.m. Wednesday. “It changed my perspective on American history. For the first time, I thought this could be true. John Wilkes Booth could have gotten away."

After researchers obtained the best images available, they fed them into a high-resolution scanner, said Scott Hartford, executive producer of Fight or Flight Studios.

“Everyone was prepared for it to not to be a match and just say, `Oh well, it was an intriguing story to try to tell...,'” he said. "It sounded like a crazy conspiracy theory, but when we looked at it, it raised legitimate questions.”

George’s photo was nearly a perfect match with Booth’s, within the top 1 percent of those bearing similar facial features, said researchers who worked with the creator of the New York Police Department’s first dedicated facial-recognition unit. What’s more, he was within one pixel of having the same eye structure.

St. Helen’s photograph, which was damaged and had to be repaired for the test, came within the top 3 percent of the digital lineup, researchers said. Police examiners give special attention to results that come up at 5 percent.

History says Booth — the matinee idol of his time — shot the 16th president in the back of the head at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865, then fled through Maryland and Virginia, where the man believed to be the assassin was cornered by soldiers and detectives shortly after 2 a.m. on a cool, cloudy Wednesday in a barn near Port Royal, Va.

“Draw up your men before the door, and I’ll come out and fight the whole command,” called a voice from the barn. “Well, my brave boys, prepare a stretcher for me!”

A soldier lit a tuft of hay, threw it inside and — amid the smoke and flames — spied the silhouette of a man on crutches, a carbine resting on his hip.

A shot rang out. The man collapsed to the ground, mortally wounded in the neck.

For historian James L. Swanson, the case is closed. “The survival myth of John Wilkes Booth, roaming across the land, evokes the traditional fate of the damned, of a cursed spirit who can find no rest,” he wrote in his book Manhunt. The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer.

But from the beginning, several people who saw the body at the barn questioned the official account. The dead man didn’t resemble the fair, raven-haired Booth, a dashing Shakespearean performer who, with his brothers Edwin and Junius, played theaters in Philadelphia, New York, and Washington.

Though others identified the corpse as Booth’s and the government confirmed the assassin’s death, questions lingered. Attempts were made in 1995 to exhume the remains from a family plot at a Baltimore cemetery to check it for identifying marks — a broken left leg and crushed right thumb — and to superimpose photographs to match the skull to photos of Booth. The judge turned down the request after determining it could not be proved where the body was buried.

“The government told us that Booth was caught and killed, and traditional historians went along with it,” said Maryland educator and historian Nate Orlowek, who has investigated the assassination since he was 15 years old and worked with a group of other like-minded historians. “They fell down on the job and ridiculed those of us who toiled for decades to disprove the hoax. We were right. John Wilkes Booth got away.”

Historian Andy Waskie, author of Philadelphia and the Civil War and associate professor in Temple University’s language department, said he is open to new insights offered by facial recognition technology. “I always support any and all practices that lead to a better understanding and concept of historical events and personalities,” he said. “If this practice can lead researchers into a clearer picture of the past, I am all for it.”

Waskie and other scholars such as Rob D’Ovidio, associate professor of criminology and justice studies at Drexel University, who focuses on high-tech crime and electronic surveillance, including facial recognition software, say new technologies can be useful. “But the evidence needs to be strong if you’re going to rewrite history,” D’Ovidio said. “This is like the History Detectives show on PBS,” which uses modern tools and old-fashioned legwork to learn more about the past.

Facial characteristics can be like a fingerprint, but much depends on “the quality of the photos,” said D’Ovidio. “That’s a huge factor. The best samples are taken in controlled environments. You’re not going to get 90 percent accuracy if you have photos of questionable quality.”

Based on various historical accounts, Orlowek is convinced that Booth fled to Granbury, Texas, and took the name John St. Helen before moving to Enid, Okla., where he was known as David E. George. An image of George’s mummified remains in 1931 also was visually compared by researchers to a picture of the embalmed George in 1903.

“This is the first time any independent scientific test has been performed to try to settle this controversy,” Orlowek said. “This high-tech test has determined there is an 99 percent likelihood that George is Booth — and now history needs to be rewritten.”