Can radical listening transform prison culture? One Pennsylvania institution is finding out.

Just Listening brings the modest act of listening — careful, attentive, empathetic listening — to people experiencing hunger, homelessness or other hardships.

When Fred first heard of the opportunity to become a trained, certified listener, he wasn’t too impressed.

Shut up. Listen. Comply. “That’s what we do every day,” said Fred, 46, who is incarcerated at the State Correctional Institution Phoenix in Montgomery County.

“But then the first thing they said to me was, ‘Listening is an act of justice,’ and that caught my attention.”

That’s the motto and the underlying theory of Just Listening, an organization that brings the modest act of listening — careful, attentive, empathetic listening — to people experiencing hunger, homelessness, or other hardships at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Phoenixville and St. Francis Inn in Kensington.

Now, the listeners have expanded into the Department of Corrections, where more than 160 men have been trained and about a dozen have become trainers themselves, using radical listening to slowly, almost imperceptibly, transform the culture inside one of Pennsylvania’s largest maximum-security prisons.

“I became more patient, more compassionate, more curious,” said Fred (as a condition of access to prison programs, publications are not permitted to print last names or show the faces of incarcerated people, or to reference their crimes), describing how listening has changed his relationships with family, other prisoners, and even guards.

It’s empowering, too. One time, when a high-ranking official unleashed a tirade in response to a prisoner’s offhand comment about an institutional issue, “I was kind of offended, but I remembered my training and listened to what was going on underneath," Fred said. “It sounds like that was a trigger for you,” he told the official, who was stunned into silence.

Just Listening was developed by Mount Airy resident Sharon Browning, 68, who for years made her career as an advocate, a talker — teaching at Chestnut Hill College, and providing legal services to people living in poverty.

But, in all that advocacy, she realized one thing was missing: “To actually listen to what people want and need, and what their ideas are.”

So Browning began to quiet down, and listen up. Twelve years ago, she switched her focus full-time to training people on listening, starting a consultancy that powers her volunteer organization.

“We train volunteers to listen to people on the social margins in some way — vulnerable people who are poor, mentally ill, addicted, really suffering, and to whom nobody listens," she said.

At St. Francis Inn in Kensington, where other volunteers arrive bearing food and warm clothing, the listeners bring only their unassuming presence, waiting to strike up a conversation or sit in silence. There’s no agenda. Yet, listening can have an impact over time, giving people the space to talk through what their goals are, and what they need to get there.

“Sometimes people need to feel respected before they can even think about anything else in their lives,” Browning said.

She recalled one man who’d been living in abandoned buildings for 20 years, resisting efforts to get him medical or psychiatric treatment. “It was a combination of a rat bite and a listener,” she said, that got him to reevaluate, seek help, and start on a path that would ultimately lead to stable housing.

But Browning never intended to bring her work into prison. It was after a speaking engagement there in 2014 that leaders of a lifers’ organization first urged her to help them create an ongoing program.

It took a couple years of negotiating the system to make that a reality, but Just Listening has been in the prison since 2017, and 168 incarcerated men have completed full-day listener training.

Felix, who’s known as Phill, said the first lessons were humbling.

“I was just struck by how horrible I am at listening: my ego, my need to tell a similar story to someone else’s story,” he said. That’s why he and the others embraced the project. They initially imagined they could serve as listeners to new prison admissions or other particularly vulnerable populations at the prison. But, given the constraints of the institution, their listening practice has been less formal, more a way of living everyday life.

They’ve also focused on continuing education. Now, each month, two of the listeners — one incarcerated, and one outside volunteer — run follow-up workshops for those who’ve completed basic listener training. And, Browning said, the incarcerated participants have overhauled the curriculum for the entire Just Listening program.

The lessons they prepare are simple, but difficult to master: Check the ego. Be curious. Be patient. Be vulnerable. Recognize your biases. Center others instead of one’s self — even if that often means ceding 14 minutes of a 15-minute prepaid call to loved ones at home.

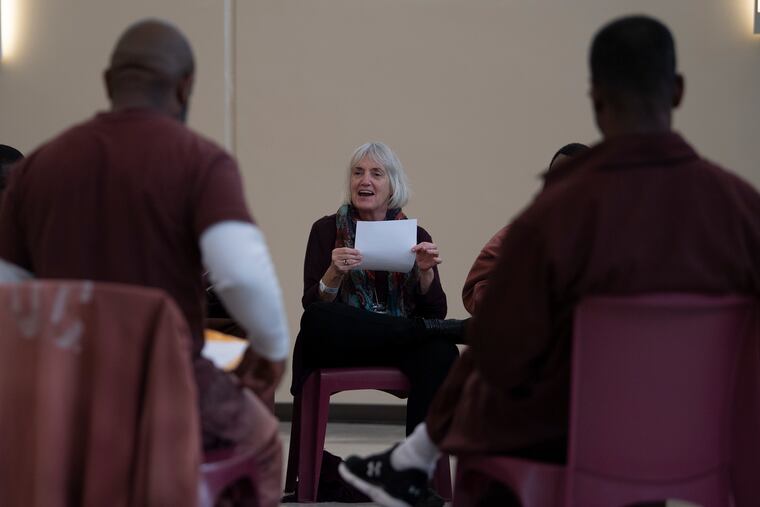

On a recent morning, security doors slid shut behind a group of volunteers who arrived in the prison chapel, and then the men filtered in, dragging plastic chairs into a circle.

The group was meeting to talk about how to spread the listening gospel — quick listening tips broadcast on prison TV, or posted to Facebook? — and to choose the topic for their next listener training.

Phill was advocating for a discussion of labels, and how those affect listening.

“‘Inmate,’ which I call the ‘I’ word, ‘prisoner,’ even ‘lifer’ — what these labels do is confine us to one aspect of our identity and cancel out everything else," he said.

John, meanwhile, had the recent exoneree Willie Veasy on his mind. “I’m thinking about how can we get people to hear that there are people in here that are innocent? [Veasy] was locked up 27 years screaming, ‘I’m an innocent man.’ And no one listened,” said John, who goes by Yahya.

For those who are part of this community, there’s a sense that listening has that kind of power, that it can overcome even the constraints of prison.

Tricia Way, one of the volunteers who comes into the prison every two weeks, said she finds inspiration here. “People are finding meaning, hope, joy, and lightness in a space designed to do the exact opposite.”

Saleem, 58, who is the president of Lifers Inc., feels the same way. It’s that rare feeling of not being talked down to, judged, or ordered around.

“For the couple hours we do have together, it’s like liberation for us," he said. "It’s like two hours of freedom.”