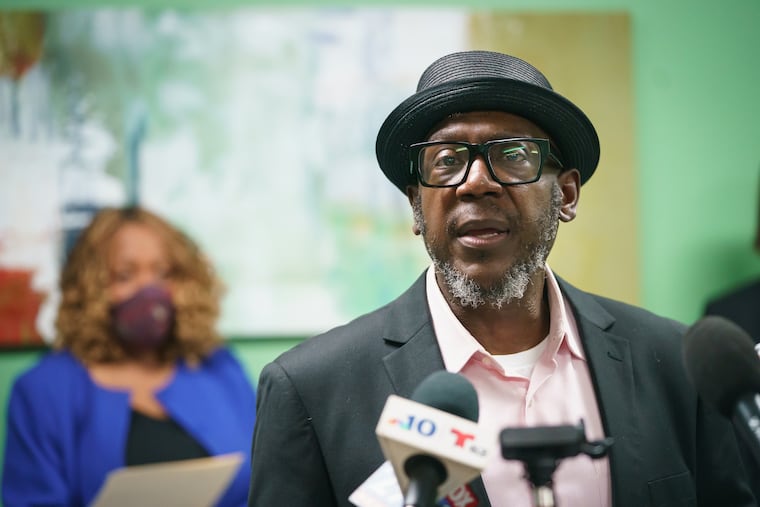

Khalif Mujahid-Ali, a devoted anti-violence advocate, has died at age 60

“He just cared in a way that was so authentic. He took every homicide personally," people said of Ali.

Khalif Mujahid-Ali, 60, a devoted community organizer who wrapped his arms around the city’s youth and “took every homicide personally,” died this week.

Mr. Mujahid-Ali, of Southwest Philadelphia, was found dead in Bellmawr, N.J., Tuesday morning, police said. While an official cause of death is not yet available, his family said they believe he died of a heart attack.

Mr. Mujahid-Ali was the founder of the Beloved Care Project, a nonprofit that sought to mentor and support children from West and Southwest Philadelphia through writing, trauma and grief counseling, field trips, neighborhood marches, and interfaith prayer. The goal, he said, was to uplift the voices of people and communities most affected by gun violence, and to “build a village” for the city’s children so that they could see a future for themselves.

“They don’t have no hope,” he said of the city’s young people in a recent interview. “We have to show them that we love them, we care, we want to save their lives.”

He was born in Philadelphia on April 21, 1963, as Lewis Edward Brooks, and attended Philadelphia public schools. He converted to Islam in the ‘70s, his family said, and adopted a new name.

Mr. Mujahid-Ali had a contagious laugh and kept a short, graying beard, and was almost always wearing a hat — his signature look was sporting a black beret.

He spent some of his adult life in Delaware, Virginia, and Maryland, and over the years, worked as a kitchen and flooring specialist at Home Depot, an associate at a county landfill, and as a truck driver.

But he did not realize his true calling until he served a 6½-year jail sentence for aggravated assault in 2014. It was during his time behind bars, he said, that the idea for the Beloved Care Project was born — he was determined to ensure other Philadelphia children did not repeat his mistakes, and that even if they did, it would not define them.

He founded the nonprofit in 2020, and funded it largely out of his own pocket as an Uber and Lyft driver. He most recently worked full-time at the Penn Injury Science Center at the University of Pennsylvania, as a community outreach supervisor and violence interrupter.

People who knew Mr. Mujahid-Ali described him similarly: He was selfless — everything he did was for his community. He was humble — he never wanted the spotlight at the events he organized, and made sure attendees were the ones holding the microphone. And, above all else, he was committed to building trusting relationships with community members, especially youth.

“His whole philosophy was, show up. He would say, ‘I don’t want your money, I want your support. This work can’t be territorial, we have to work together,’” said friend and confidant Natasha McGlynn, executive director of the Anti-Violence Partnership of Philadelphia.

McGlynn recalled the first time she met Mr. Mujahid-Ali, at a community meeting in early 2021, where he told the group that he regularly cried for the city’s children and the violence they were enduring.

The two spoke almost daily after that. “I had a 60-year-old best friend,” said McGlynn, 37.

“He wanted to make a change and he wanted voices to be heard,” said Mecca Robinson of Forget Me Knot, who organized anti-violence events with Mr. Mujahid-Ali. “We really lost a soldier.

Mr. Mujahid-Ali personally knew the pain wrought by gun violence — in 2009, his sister Tara Monique Brooks was fatally shot.

He was tired of politicians and institutions telling his community what they thought they needed, he said, and wanted those most impacted by violence to be heard.

“You can’t walk in our house and tell us how to fix it,” he told The Inquirer. “We’re gonna tell you how to fix it.”

Recently, he’d become a key volunteer for mayoral candidate Rebecca Rhynhart’s campaign and appeared in multiple commercials.

Rhynhart called Mr. Mujahid-Ali’s anti-violence work “inspiring and contagious.”

“Khalif genuinely believed we could improve our neighborhoods through compassion — and I hope we all can lead by following his example,” she said in a statement.

Rhynhart’s campaign manager, Kellan White, added: “He just cared in a way that was so authentic. He took every homicide personally. Whether it was Northeast Philly, Center City, Southwest, Black, white, Hispanic, Asian, didn’t matter to him. It was all a disease that was warping our city in a way that was unacceptable to him.”

Mr. Mujahid-Ali built close relationships with many families who’d lost loved ones to gun violence, standing alongside mothers such as Crystal Arthur, whose son Kristian Hamilton-Arthur was killed in 2017, to call for justice in their unsolved cases.

“We have to keep it alive,” Arthur said. “We can’t just let the Beloved Care Project go. His legacy has to be fulfilled.”

Family was at the heart of all of his work, McGlynn said. He was a loving son and father and was especially devoted to his grandchildren, said his niece Shannon Brooks.

Even if he was in a meeting, she said, when his twin granddaughters called him, he stopped what he was doing and answered the phone.

“They were inseparable,” Brooks said.

Mr. Mujahid-Ali is survived by his mother and children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews. A janazah prayer will be held Saturday, May 13, at 1 p.m. at the West Philadelphia Masjid, at 4700 Wyalusing Ave.