One North Philly woman’s fight to end life without parole sentencing

The Amistad Law Project’s new documentary “No Way Home” examines the painful effects of life imprisonment and the efforts to end it in Pennsylvania

Sometimes, Lorraine Haw has to remind herself that her son is no longer a child.

“He’ll always be my baby,” the woman known by her North Philly friends and family as Mrs. Dee Dee said. Her son, Phillip Ocampo, is 47 years old now. “He was always a great kid, since he [could] talk. He was always a great kid. Just hung out with the wrong people and grew up [under] not too good circumstances.”

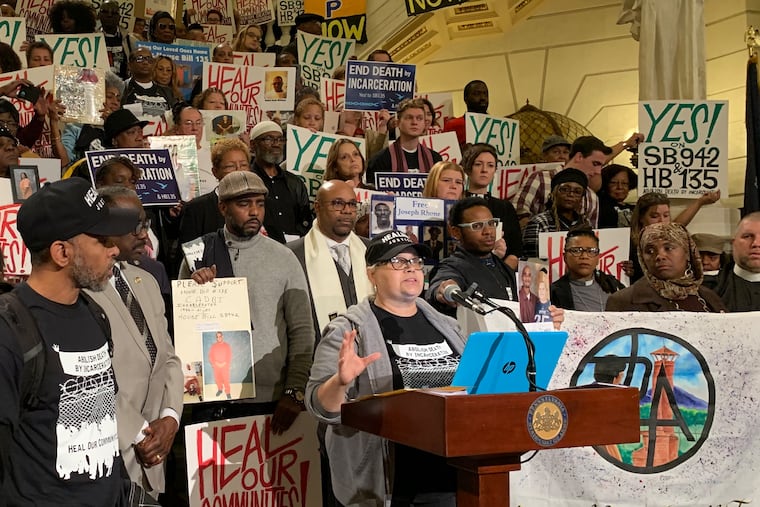

When he was 18, Ocampo was convicted of second degree murder, also known as felony murder. In Pennsylvania, that requires a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. But Mrs. Dee Dee, an organizer with the Coalition to Abolish Death by Incarceration, is determined to make sure that her son does not die in prison.

“I always tell him he’ll be coming home, because I believe [that] with all my heart,” she said.

Mrs. Dee Dee is fighting tirelessly to get her son’s sentence commuted, and to end life without parole (LWOP) sentencing in the state. Her efforts are the subject of a new documentary created by the Amistad Law Project, No Way Home.

“It’s a film about our human potential to change for the better. And the core message there is that people can and do turn their lives around,” said Sean Damon, organizing director of Amistad.

“We are advocating for a system that offers a second chance to people who rehabilitate themselves instead of condemning them to die in prison.”

Amistad will host a series of screenings of No Way Home this summer. Each screening will be followed by a town hall discussion about LWOP and the fight to end it.

The first screening and town hall will take place on June 15 at 6:30 p.m. at the Chester Culture Arts and Technology Center, located at 2300 W. 4th Street, Chester, Pa. 19013. The panel will feature Mrs. Dee Dee, Damon, and other leaders working to end LWOP.

Philadelphia’s first screening will be held on June 30 at 6:30 p.m. at the Parkway Central branch of the Free Library, located at 1901 Vine Street. More screenings across Pennsylvania, as well as virtual ones, will be planned in the coming months.

Philly’s 2,700 LWOP sentences

Philadelphia is uniquely situated for these conversations. According to research from the Abolitionist Law Center, there are almost 2,700 people from Philadelphia currently serving LWOP sentences, more than any other county or parish in the United States.

That number is so high in part because Pennsylvania is one of only six states that mandate an LWOP sentence for a crime other than first degree murder. In Pennsylvania, Felony murder has the same sentence. Prosecutors issue this charge when a person is killed while another felony, like an armed robbery, is being committed.

This is how Ocampo got his LWOP sentence — in March 1994, he and a group of friends took part in a robbery of a rival drug dealer’s house. The house was usually unattended, but the dealers came home suddenly while Ocampo and his friends were there. During the ensuing gunfight, one of Ocampo’s co-defendants shot and killed one of the other men.

» READ MORE: Fetterman was vilified for promoting life sentence commutations, but research shows his approach is the right one

“I think he’s doing better than me and I’m the one out here,” Mrs. Dee Dee said, amazed at how positive her son remains while enduring his harsh punishment. Ocampo had two daughters before he went away to prison, and he communicates with them and his eight grandchildren as much as he can.

Over the years, he’s also earned several educational certificates, has helped paint and build houses, and raised service dogs for people with disabilities.

“My focus is my family and my grandchildren. I didn’t have the opportunity to raise my children physically, but this gives me a chance at least to raise my grandchildren physically,” Ocampo said about his potential release in the documentary.

“The practice of extreme sentencing is [very] destabilizing for families and communities. You are disappearing people that, had they had a chance to rejoin the community after turning their lives around, they could be a positive influence,” Damon said.

“They could be role models, mentors, people who serve as a cautionary tale of ‘don’t go down this road that I went down.’”

‘They should be allowed a second chance.’

Currently, the only way for someone like Ocampo to come home is to be pardoned for their crime, or to have their sentence commuted, or shortened, by Pennsylvania’s Board of Pardons and the governor. Ocampo has applied for commutation, and his case will continue to move forward in that lengthy process this year. But his successful release is far from certain.

“[Commutation] used to be a pretty common practice ... in the sixties and seventies, but with the rise of mass incarceration policies in the United States, that process was effectively derailed,” Damon said. He said that with over 5,000 people in Pennsylvania imprisoned under LWOP now, the commutation system has to sort through many more cases than it was ever designed to handle.

“It’s a huge bottleneck,” he said.

There has been some legislative movement towards expanding parole eligibility for those sentenced to LWOP, like a 2021 PA Senate bill that would have made individuals over 55, or with certain chronic illnesses, parole eligible. But that bill or others like it have yet to go into law.

As they keep fighting and advocating for change, there is clear evidence of the redemption that Damon and Mrs. Dee Dee speak of. After the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed mandatory LWOP sentences for juveniles in 2012, in 2016 it ruled that prisoners serving those previously issued sentences must be resentenced and become parole eligible.

In Pennsylvania, nearly all of the juvenile lifers have since been resentenced, and about 65% have been paroled. Of that group of prisoners who have been granted parole, their recidivism rate is a mere 1%.

“Just because someone made a mistake in their life and they’re paying for it in prison, they shouldn’t rot in prison. They should be allowed a second chance. Especially if they have rehabilitated themselves and they’re remorseful for the mistake that they’ve made,” Mrs. Dee Dee said.

“Do y’all really think an 80-year-old man can do [something harmful] today? And why do you have prisoners in their own wheelchairs and that are dying of cancer?”

Mrs. Dee Dee is frustrated by her son’s circumstances, but never lets him feel like he’s too far away or forgotten. She talks to him on the phone every day, and takes every one of her six allowed visits per month to see him in person. Ocampo’s grandchildren see him on video visits every now and then, too.

“They love visiting with pop-pop,” she said.

She’s been taking community college classes for about a year now. Her major is criminal justice, and she is hoping to use her degree to continue helping Phillip and other people like him.

“I wanna see if I can run for something,” she said. “So that someone [else’s] child don’t have to go through what I went through with mine.”

“If I don’t fight for him, how can I wait for anybody else to fight for him?”