This Philly lawyer works to empty death row. His new book reveals an absurd, broken system.

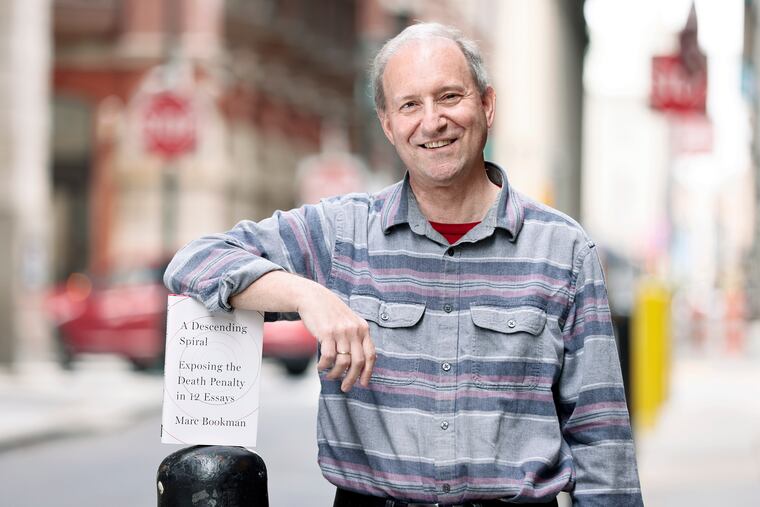

Marc Bookman, co-founder of the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation, is the author of "A Descending Spiral: Exposing the Death Penalty in 12 Essays."

From the very first death-penalty appeal he worked on, Marc Bookman came to understand how crucial writing can be in life-and-death matters. The verdict form was missing a single “s” — an error that changed the meaning of the verdict enough to overturn the sentence.

The case also left him with a sense that the entire system of capital punishment can be arbitrary and even absurd, a view that was cemented when he became part of the first team of lawyers handling homicide cases for the Defender Association of Philadelphia. In 2010, he cofounded the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation, a nonprofit death-penalty resource center.

Over the years, he’s applied his writing skills to pieces published in The Atlantic, Slate, and Mother Jones, among others. His first book, A Descending Spiral: Exposing the Death Penalty in 12 Essays, published by The New Press, was released this month. The essays — some dealing with cases he worked on, most cases researched through public records — circumvent the moral arguments for and against the death penalty and reveal the foibles of the system in practice.

Bookman will speak as part of the Free Library’s virtual author series on May 20 at 7:30 p.m. He spoke with The Inquirer about his book and life’s work. This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Why did you want to write this book?

At a personal level, the death penalty has become a very important issue to me over 40 years. When you work closely in the system from the defense side, you see how outrageous the death penalty is.

There are moral arguments on both sides. But there’s a reason the prosecution tries to limit how much the jury knows about the person who is accused, because if the jury spent 30 minutes just talking to the guy — whether he is severely mentally ill, low functioning, or just did an absolutely terrible thing — the jury would never vote to execute him. The jurors would immediately see the humanity in the person, however that manifested itself.

I would like to think that this book sheds some light on just how hypocritical our system of capital punishment is. It’s a public policy. I feel like the more people know about how the system of capital punishment really works, the less support they will have for that policy.

» READ MORE: Philly’s overturned murder cases call decades of homicide investigations into question

Was there a case that first gave you the sense this is a dysfunctional system?

Percy St. George was one of my very first capital cases — a case that was withdrawn after it came out that detectives had fabricated statements, and the detectives then pleaded the Fifth. I had another case that was incredibly early in my career where a guy got very drunk, shot his wife, called the police, and was holding a bottle of whiskey in his hand when they came to arrest him. But in the discovery there is no evidence of any alcohol. We keep filing motions asking, ‘Where is the alcohol?’ They keep denying that there’s alcohol. Finally, right before the trial, the crime scene person starts getting nervous and turns over discovery. It turns out they took a lot of pictures of the alcohol, but they didn’t develop any.

That case and Percy St. George were among my first five homicide cases. So what’s a normal person to think? They’re going out of their way to convict on the highest charge no matter what. When did I realize how much corruption went into these cases? Early, really early.

How did you select the cases in the book?

First, it’s important to say: These cases seem absolutely absurd — but people should not come away thinking these are 12 outrageous, crazy, beyond-the-pale cases. What’s important about these is they are typical of capital cases.

I would take a topic: There are sleeping lawyers, racist lawyers, drug-addicted lawyers. There are lawyers that are about to be disbarred. I just looked for an example. Every one of these stories, when I get into it, is a better story than I realized, and every one is just the tip of the iceberg. Often, you’re talking about a level of advocacy that is so low it’s remarkable — and lives are at stake.

For instance, a lot of times when a lawyer will give a jury an example of a reasonable doubt, he’ll give a hypothetical. So this one defense lawyer said, “A reasonable doubt is a hesitation that you would have in a serious matter in your own life. So say, for example, you want to buy a car, it’s reasonably priced, and then you look under the hood and you see rust. This makes you think. Then you look a little more and you realize the rust is not all that significant. So you buy the car.” This is a lawyer that doesn’t even understand his own hypothetical! The whole hypothetical is the rust is supposed to give you a reasonable doubt about the car. He tells the jury he bought the car.

» READ MORE: Dozens accused a detective of fabrication and abuse. Many cases he built remain intact.

You include a chapter on Terrance Williams, a Philadelphia teen who was convicted of two murders, and sentenced to death in the 1980s. (He has since been resentenced to life without parole, and has ongoing appeals.) Why focus on that case?

The Terry Williams story encapsulates virtually everything that’s wrong with the death penalty. He’s a kid who older men have been preying on since he was 13 years old. I think most people would say if you’re sexually abused and you kill your abuser, you’re not the worst of the worst. So you would think the reasonable prosecutor, even if they believe in the death penalty, might not seek it in that case.

Instead, the prosecutor does everything possible to get that death sentence. His first case involves this sexual abuse — and the jury comes back with third-degree murder. That conviction has since been dismissed.

And then, in the second trial, after the prosecutor doesn’t get first-degree murder in the first case, she then approaches the second case by keeping out all the evidence about sexual abuse. [The prosecutor in the case has denied that any evidence was withheld.] Then, there’s a defense attorney who doesn’t look to find the evidence he needs, who meets the client only one day before trial. And you have a case that never should have been capital in the first place.

That story captures everything: bad lawyering, and a Commonwealth that is refusing to look at the facts of the case. And he’s just a kid. What more do you need?