On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, remembering the women civil rights leaders left out of spotlight

“Women were at the forefront of the civil rights struggle, but their individual stories were rarely heard,” said Bettye Collier-Thomas, a professor of history at Temple University. She is co-editor of "Sisters in the Struggle: African-American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement."

As the country observes Martin Luther King Jr. Day on Monday, there will be many news clips of the civil rights leader at the 1963 March on Washington.

That iconic image of King delivering the “I Have a Dream” speech to 250,000 at the Lincoln Memorial is seared into the history of the struggle for equal rights. But generally, beyond Rosa Parks refusing to relinquish her bus seat, little is known about the women of the civil rights movement.

“Women were at the forefront of the civil rights struggle, but their individual stories were rarely heard,” said Bettye Collier-Thomas, a professor of history at Temple University. She is co-editor of Sisters in the Struggle: African-American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement.

Those unsung women activists included: Daisy Bates, Ella Baker, Septima Poinsette Clark, Diane Nash, Fannie Lou Hamer, Gloria Richardson, Amelia Boynton Robinson, and Anna Arnold Hedgeman.

They led Freedom Rides; organized citizenship and freedom schools; persuaded poor, rural blacks to try to register to vote; fought for economic justice; organized political parties; lost their jobs; went to jail — and were beaten while there.

Dorothy I. Height, the longtime president of the National Council of Negro Women, wrote an essay for Collier-Thomas’ book titled ”We Wanted the Voice of a Woman To Be Heard.” The chapter described how women argued for having a woman give a major speech at the march. “They [the male organizers] said, ‘We have too many speakers as it is. The program is too long. ... We have Mahalia Jackson.’ “ The women countered that she was singing, not speaking.

At the last minute, organizers agreed that Daisy Bates, president of the Arkansas NAACP who mentored the “Little Rock Nine,” the first black students to desegregate Central High School there in 1957, should present a “Tribute to the Negro Women Fighters for Freedom,” according to the Anna Julia Cooper Center at Wake Forest University. Bates spoke in the place of Myrlie Evers, whose husband, Medgar Evers, had been shot and killed earlier that year because of his voter registration work.

“Most of the people who were arrested and put in jail during the civil rights movement were women and children,” said Mary Frances Berry, a Geraldine R. Segal Professor of American Social Thought and History at the University of Pennsylvania, whose latest book is History Teaches Us to Resist: How Progressive Movements Have Succeeded in Challenging Times.

People referred to the prominent male civil rights leaders as the “Big Six”: King, A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy Wilkins, and Whitney Young.

The men of the movement “were male chauvinists like most males of the period,” Berry said. She added that many people didn’t realize that King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, was a “crucial player. Coretta, for example, strategized, gave advice, and knew as much as Martin did, or more, about nonviolence.”

Here are some women in the movement, selected by academics and activists:

Ella Baker had leadership roles in the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and was key to the founding of SNCC, or the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. After black college students began lunch-counter sit-in protests in 1960, Baker urged students from different colleges to meet at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., and helped to found SNCC. In the 1940s, as an NAACP field secretary and later, as director of branches, Baker traveled the South encouraging black people to fight for their human rights. Rosa Parks attended one of Baker’s workshops.

Baker, who died in 1986 at age 83, is famous for the quote “Until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons, becomes as important as the killing of a white mother’s son, we who believe in freedom cannot rest until this happens.”

Fannie Lou Hamer, born to a family of Mississippi sharecroppers, had to leave school at 12 to help her parents. After SNCC organizers went to Mississippi to open freedom schools and help people register to vote, she became a leader in her own right. In June 1963, she was jailed and beaten badly after she and other activists left a citizenship workshop. Without a college education, she was a powerful speaker and singer at civil rights gatherings. As a founder of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Hamer testified before the credentials committee of the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City on Aug. 22, 1964. She charged that the all-white Mississippi Democratic delegation had been illegally elected in a segregated election system.

She was 59 when she died in 1977. Among Hamer’s notable quotes: “We are sick and tired of being sick and tired.” “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.” And, “If I am truly free, who can tell me how much of my freedom I can have today?”

Diane Nash was a 22-year-old Fisk University student when she led lunch-counter sit-ins in Nashville. She later helped the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) when it began Freedom Rides, where black and white college students rode buses from Northern states to the South to challenge segregation. After white men firebombed buses and beat students when they arrived in Alabama, Nash insisted on leading more students to Alabama to continue the bus rides to Mississippi. She was a founding member of SNCC. She also was a leader in the Selma marches in 1965.

“She was a dynamic leader, and she still is,” Berry said of Nash, who is 80. “She had courage. The Freedom Rides would not have continued without her.”

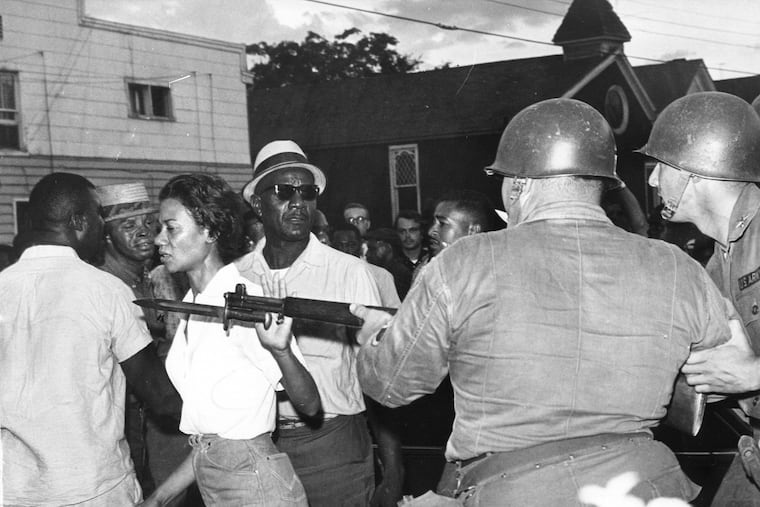

Gloria Richardson, born in Baltimore to a middle-class family, was a civil rights leader in Maryland. She moved to Cambridge as a child. After SNCC came to Cambridge, Richardson helped create the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee. She expanded the group’s protests from merely desegregating public spaces to questioning housing and employment discrimination. Now 96, she is famous for a photo in which she was brushing off a bayonet-wielding law officer at a protest.

>>READ MORE: Real-life activists from the Selma voting rights campaign visit Germantown Friends Meeting

C. Delores Tucker, former Pennsylvania secretary of state, led a Philadelphia delegation to the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march, as well as to the 1963 March on Washington, said Faye Anderson, a Philadelphia activist for historic preservation. After King’s assassination, Coretta Scott King asked Tucker to set up an affiliate of the King Center, which became the Martin Luther King Association for Nonviolence in Philadelphia.

In the 1990s, Tucker became widely known for her protests against misogyny and obscene lyrics in rap music. She went so far as to protest the NAACP, of which she was a board member, for nominating rapper Tupac Shakur for an Image Award. Anderson said Tucker, who died in 2005 at age 78, would be upset that her organization on Monday will be honoring Sheriff Jewell Williams, who has been accused of sexual harassment. Thera Martin, a spokesperson for the association, said that Williams has been an advocate for civil rights and that the association does not believe the allegations.

“She knew it was not just entertainment,” Anderson said of the rap lyrics. “It feeds into implicit bias [where people form opinions about black people based on the lyrics]. It was about self-respect and how we present ourselves to others.”