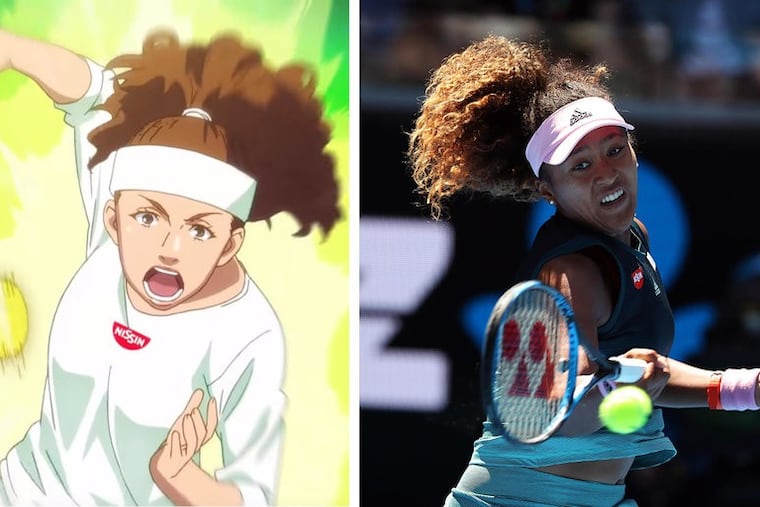

Cartoon turns tennis star Osaka’s brown skin light: ‘This is an especially stark version of whitewashing.’

“She has a tennis racket in her hand, but other than that there is no resemblance,” said one Temple University professor. "This is an especially stark version of white-washing.”

Lori Tharps couldn’t believe it when she first saw the Japanese noodle ad depicting tennis star Naomi Osaka, who is half-Haitian and half-Japanese, with white skin.

“She has a tennis racket in her hand, but other than that, there is no resemblance,” said the Temple University professor. "This is an especially stark version of whitewashing.”

Critics also noted that not only did the anime drawing by Takeshi Konomi show Osaka with very pale skin, but it straightened her naturally curly hair. It’s true that many anime characters are drawn with lighter skin, but there are examples of black characters, Tharps said, especially men: Dutch, the leader of the Black Lagoon Company, for instance.

Neither Osaka, who is currently competing in the Australian Open, nor Konomi, the well-known manga artist who drew the cartoon, has commented on how Osaka’s skin color was portrayed in the ad that was released this month, according to a New York Times report on the controversy. But a spokesperson for Nissin, one of the world’s largest instant-noodle brands, issued an apology Tuesday.

"There is no intention of whitewashing. We accept that we are not sensitive enough and will pay more attention to diversity issues in the future,” said Nissin spokesperson Daisuke Okabayash in a statement.

In the meantime, fans of Osaka, the 21-year-old who became a star in September when she defeated Serena Williams in the U.S. Open, have made clear their disappointment on social media.

Anne Ishii, the executive director of Asian Arts Initiative in Philadelphia, has worked with manga comic artists for a dozen years, translating comics from Japan into English. Many times, manga is drawn in either black or white, and artists aren’t used to distinguishing different ethnicities.

She said she knows the work of the artist who drew Osaka, and believes it wasn’t intentional.

“I think it’s a lack of experience and awareness of what it means to depict people of different colored skin,” said Ishii, who is of Japanese and Korean American descent. “I don’t think there was an editorial meeting and someone said, ‘Let’s lighten her skin.’”

Tharps, an associate professor of journalism and author of Same Family, Different Colors: Confronting Colorism in America’s Diverse Families, has researched biracial identity and colorism — the concept of favoring people with lighter skin over darker skin. Tharps herself is African American.

Japan, she said, has a very long history in colorism.

“They very much prize white skin," she said, so "it’s almost more surprising that the company, Nissin, they are a sponsor of hers — they’re championing her — and then they whitened her.”

Biracial identity came to the forefront in Japan in 2015, when Ariana Miyamoto, who is half-Japanese and half-African American, won the Miss Universe Japan pageant in 2015; some complained she didn’t look Japanese enough.

The noodle ad was not the first time a cartoon portrayal of Osaka erased her of her Haitian or Japanese background: After her win at the U.S. Open, in which Williams challenged a referee, an Australian newspaper cartoonist depicted Williams as an overweight child with very thick lips while Osaka appeared tiny — and blonde.

Unlike in the United States, the Caribbean and Latin America, where colorism is about identifying with white people of European descent, Tharps said the desire for lighter, whiter skin in Asia has more to do with class and privilege going back hundreds of years in countries like Japan, Korea, and China.

Being light skinned indicated a person was wealthy enough not to work in the fields and wasn’t of the peasant class. It also meant that person was considered educated and sophisticated. People with darker skin were seen as uncivilized.

Eventually, Tharps said, it will be Osaka herself — her winning streak, her increased visibility — that will bring to the forefront a conversation on race and identity in Japan.

“Maybe people will start thinking, if we can accept Naomi, then we can accept other black-Japanese or mixed-race people,” she said. “It takes one or two people who have a big impact to get the conversation going.”