A chaotic final night for U.K. Parliament leaves Boris Johnson with bleak choices on the path to Brexit

The prime minister's options have narrowed after a series of apparent miscalculations.

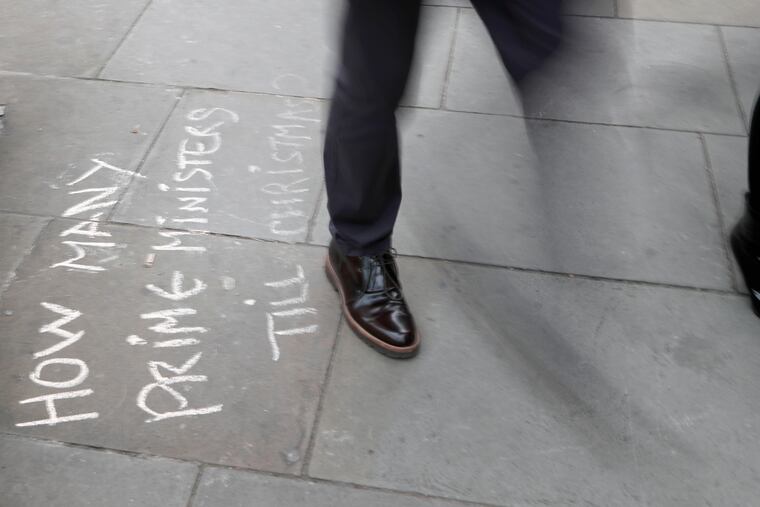

LONDON — British Prime Minister Boris Johnson faced a charred political landscape Tuesday morning that offers few viable options for achieving his “do or die” exit from the European Union, hours after Parliament crushed his dreams of an election that could clear the path to departure.

In a chaotic final session — marked by scenes of pandemonium in the wee hours of Tuesday — Johnson’s bid for a new vote was soundly defeated, continuing a remarkable streak in which the once-swaggering prime minister has lost every key vote of his young premiership.

Tuesday was the second time in as many weeks that Johnson had asked for Parliament to allow a fresh election, only to be rebuffed by a unified opposition.

With Parliament suspended for the next five weeks — under a schedule that Downing Street itself devised — Tuesday’s defeat leaves Johnson with virtually no chance of getting a fresh vote before Oct. 31, the deadline by which Britain is due to leave the E.U. And it gives him no time to overturn a rebel-backed law that requires the Britain to seek another delay if no deal can be reached by Oct. 19.

After the vote, Johnson once again insisted he will never ask for an extension, having said last week he would "rather be dead in a ditch." But the law gives him no choice. Top ministers have said in recent days that the government plans to "test the law to its limits," implying they may seek to skirt its requirements. Some hard line Brexiteers have suggested he become "a martyr" to the cause, and allow himself to be jailed for contempt.

Johnson on Tuesday morning was expected to meet his Cabinet, which has endured defections in recent days — including by the prime minister’s own brother.

The post-midnight vote capped an extraordinary eight-day stretch in which Johnson's plans were repeatedly thwarted by a Parliament that, in normal times, nearly always complies with the government's wishes.

The rebellious mood in Westminster reached a fever pitch just before 2 a.m. Tuesday, with lawmakers attempting to halt a suspension of Parliament that Johnson had ordered and that will extend until mid-October. Government opponents waved placards reading "Silenced," shouted "Shame! Shame!" at Conservative members and tried to physically block Speaker John Bercow from leaving his chair.

Bercow, who on Monday afternoon had dramatically announced plans to step down from the job, made clear he sided with the protesters, calling the decision to bar the doors of Parliament amid the political crisis of Brexit "an act of executive fiat."

Bercow, whose lion-taming skills in the circus that is Parliament have made him a YouTube star, had surprised his colleagues with the resignation announcement, and set off a scramble to replace him. The irascible lawmaker has become a polarizing figure in a country divided sharply along Brexit lines.

The outcome of Monday night’s election debate was not a surprise, with the opposition having earlier announced it would do everything it could to block Johnson’s bid for a new vote. But with an election still in the offing — likely in November — both sides of the aisle were clearly playing for votes.

"Why are they conniving to delay Brexit?" Johnson taunted as the rowdy debate kicked off, with his fellow Tories cheering him on. "The only possible explanation is they fear we will win."

"We're eager for an election," countered Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the opposition Labour Party. "But as keen as we are, we are not prepared to risk inflicting the disaster of no deal" on the British public. Opposition leaders have repeatedly said that Johnson's election offer is "a trap" intended to get a back door to no deal.

The prime minister had hoped an election could restore the majority he lost last week through a combination of defections and ejections and give him a free hand to follow through on his promise to lead Britain out of the E.U. — even if there’s no deal with European leaders.

With that option off the table, analysts say Johnson's best hope may be to strike a slightly improved deal with the E.U.

European leaders, however, appear in no mood to give ground, and Johnson may struggle to get any agreement passed in Parliament even if they do.

The sudden narrowing of Johnson’s options represents a remarkable turn of events for a prime minister who, less than two weeks ago, appeared to control his own destiny — and the fate of Brexit.

As summer waned, he announced a plan to suspend Parliament for much of September and half of October, leaving lawmakers with little time - perhaps not enough, some theorized - to block him from leading Britain over the cliff of a no-deal Brexit if no agreement could be reached.

But the formerly fractious opposition quickly unified to disrupt his plans. When he offered an election just two years after the last one - something opposition leaders had repeatedly demanded - they turned him down. Along the way, Johnson shed allies, including his own brother, who resigned from the cabinet.

A series of halting public performances added to the sense that Johnson, in office since only late July, had already begun down the path of his two predecessors, David Cameron and Theresa May, who were both casualties of treacherous Brexit politics.

"It's possible that every single defeat and every awkward speech and all the difficulties were part of some master plan to produce a future election victory," said Tony Travers, a political scientist at the London School of Economics. "But if you stand back and look at what's going on, they have, to a degree, lost control of events."

Whether he can regain that control could hinge on his dealings with Europe in the coming weeks.

Earlier on Monday, Johnson had struck a notably conciliatory tone during a visit to Dublin — an indication, perhaps, that the prime minister knows his best hope for escaping his Brexit quagmire lies with his European counterparts, who are eager to avoid a chaotic British exit.

Standing beside Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, Johnson insisted again that Britain "will come out on October 31." But he also cited a clear preference for a deal to manage the withdrawal and said there is still plenty of time to come to terms before E.U. leaders meet for a summit Oct. 17-18.

"There is a way forward," he said. "If we really focus, I think we can make a huge amount of progress."

He declined, however, to specify new proposals. And Varadkar maintained that he had not seen any.

The Irish leader also savaged a favorite Johnson talking point, insisting that a British exit without a deal would lead only to more rounds of negotiation — not to an end to Britain’s Brexit agony.

"There is no such thing as a clean break," Varadkar said as Johnson grimaced.

A joint statement following the news conference and a subsequent hour of meetings said that "common ground was established in some areas although significant gaps remain."

The question of how to handle the border between Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom, and the Republic of Ireland, which will remain a member of the E.U., has bedeviled Britain’s Brexit plans from the start — and will be key to talks in the coming weeks.

Both the British and Irish governments say they don't want a hard border, complete with checkpoints and barriers, dividing the island. But the Irish, and the E.U., have insisted on a "backstop" that would in effect keep Britain in the E.U.'s customs union until a solution can be found that allows for two trading systems to exist side by side.

Johnson has rejected such an arrangement, saying it would keep Britain from striking deals with other countries, such as the United States, and reaping the benefits of life outside the E.U.

If there are benefits to be had, they remain stubbornly elusive three years after a majority of Britons voted in a referendum to exit the E.U.

With the country still polarized along Brexit lines, polls show Johnson’s Conservatives with a significant lead over the opposition Labour Party. Whenever an election comes — analysts say November is now likely — the prime minister is expected to play on frustration among pro-Brexit voters who blame Corbyn and other opposition leaders for the country’s inability to get out.

But with multiple choices for both the pro- and anti-E.U. sides on the ballot, any election is highly unpredictable.

Just how polarized Britain has become was evident Monday afternoon with the surprise announcement by speaker Bercow that he would leave his post by the end of October.

Known for his enthusiastic shouting of "Order! Order!" as well as his loud ties and his soaring oratory, Bercow is a cult figure in the Brexit drama.

He is also a stalwart defender of parliamentary power, one who used his traditionally low-key and nonpartisan role to ensure that lawmakers could effectively check executive power at a time when critics say Johnson is flouting important conventions of the British political system.

That stance was significant last week, with Bercow giving lawmakers the chance to block Johnson's attempts to take Britain out of the E.U. without a deal.

Most lawmakers gave Bercow a standing ovation on Monday — a rare display on the House floor. But many hard line Brexiteers, who believe Bercow is biased toward the pro-E.U. camp and had vowed to try to defeat him in the next election, stayed seated.

In an emotional farewell address, with his wife looking on from the gallery, Bercow pleaded for an institution that is taking heavy abuse as frustration with Britain’s interminable E.U. exit builds — and is likely to take more.

“We degrade this Parliament at our peril,” he said.