Hiroshima marks the 75th anniversary of atomic bomb attack

"We must never allow this painful past to repeat itself. Civil society must reject self-centered nationalism and unite against all threats."

HIROSHIMA, Japan — On the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing of his city, the mayor of Hiroshima warned the world about the rise of "self-centered nationalism" and appealed for greater international cooperation to overcome the coronavirus pandemic.

Speaking at a Thursday morning ceremony in Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Park — near the center of the Aug. 6, 1945, blast — Kazumi Matsui renewed a "Peace Declaration" on behalf of the city and appealed to Japan's government to ratify a 2017 U.N. treaty proposing the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Seventy-five years after the bombing of Hiroshima, humanity struggles against a new threat: the novel coronavirus, Matsui said. "However, with what we have learned from the tragedies of the past, we should be able to overcome this threat."

"When the 1918 flu pandemic attacked a century ago, it took tens of millions of lives and terrorized the world because nations fighting World War I were unable to meet the threat together," he said. "A subsequent upsurge in nationalism led to World War II and the atomic bombings.

"We must never allow this painful past to repeat itself. Civil society must reject self-centered nationalism and unite against all threats."

The memorial events have been drastically scaled back this year because of the pandemic. Crowds usually reaching in the tens of thousands were kept away. Just 880 seats, spaced six feet apart, were placed on the lawn of the park, reserved for dignitaries, children, survivors of the bomb attack and families of those killed.

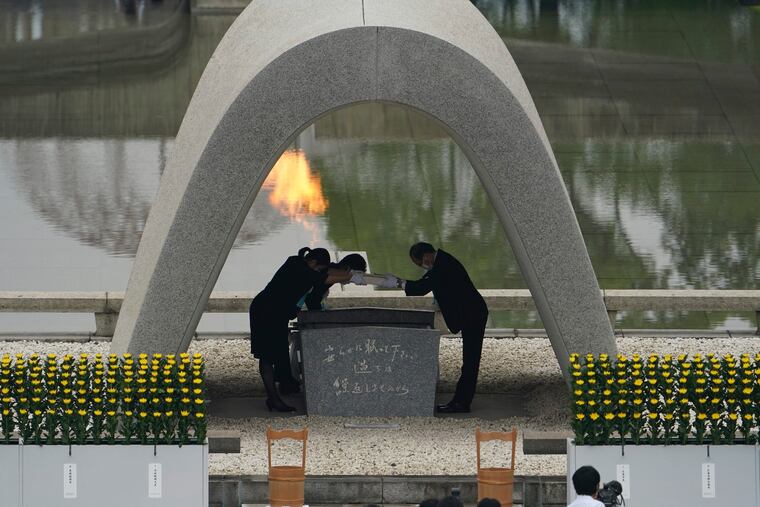

Flowers were laid at a cenotaph dedicated to the victims, a bell tolled as the audience bowed their heads in prayer, and children sang a song for peace.

The traditional release of hundreds of doves was canceled after the pandemic prevented the birds from being trained to return home. Also called off to avoid crowds: a public ceremony to float thousands of paper lanterns on Hiroshima's Motoyasugawa River, Japanese media reported.

Last year, Matsui also warned against rising nationalism, but his latest appeal takes on an added significance — the New START, or Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia, is due to expire in February, and there is speculation it may not be renewed, unwinding decades of efforts to limit nuclear arsenals.

That follows the U.S. decision to pull out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces, or INF, treaty in 2019, accusing the Russians of cheating. Meanwhile, North Korea's nuclear arsenal continues to grow after the collapse of U.S.-led efforts to strike a disarmament deal with Kim Jong Un.

"The web of arms control, transparency and confidence-building instruments established during the Cold War and its aftermath is fraying," U.N. Secretary General António Guterres warned in a video message. "Division, distrust and a lack of dialogue threaten to return the world to unrestrained strategic nuclear competition."

Survivors of the Hiroshima blast also found common links between the threat of nuclear radiation and global fears of COVID-19.

"People around the world must work together, must fight this disease, must learn together," said Keiko Ogura, who was 8 when the atomic bomb struck 1.5 miles from her home in the north of the Hiroshima. "That's the kind of sentiment that we had when we were calling for elimination of nuclear weapons."

Ogura was knocked unconscious by the blast and awoke to find houses gutted or engulfed in fire, and a line of burned and injured people gradually emerging from the city center.

She has spent her life calling for the elimination of nuclear weapons, and she says she sees encouraging signs that young people are taking up the campaign. But she warned that complacency could easily see the world sliding rapidly downhill toward nuclear war.

“It’s very much like the fear of the second or third wave of COVID-19,” she said. “I feel the same sense of crisis.”

Ogura, 83, is one of a dwindling band of survivors, marking a new challenge in preserving memories of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which took place three days later on Aug. 9, 1945, and preceded Japan's surrender in World War II.

Kai Bird, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian at the City University of New York, laments America's inability to have a national conversation about the need for the bombings. "It's verboten, we are still in love in the bomb it seems," he said.

In an online briefing organized by the Institute for Public Accuracy, Bird and other historians argued that U.S. leadership knew Japan was about to surrender as the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan by invading Manchuria in August 1945.

Many senior U.S. military figures shared that view, including Adm. William H. Leahy, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who called the bombing of Hiroshima "barbarous" and "of no material assistance" in ending the war.

But other historians differ, arguing the bombings had a decisive impact in persuading Emperor Hirohito to surrender, and that delay would have cost more innocent lives.

In Japan, the memory of Hiroshima has fueled a national sense of the country as victim rather than perpetrator of the war, diminishing the memory of the intense militaristic nationalism that led it down such a destructive path.

Indeed, the reluctance of many Japanese people to confront its militaristic past in Asia continues to sour relations with its neighbors. In Japan, the government has been criticized for helping obscure the memory of Japan's war crimes, including removing some references from school textbooks.

Speaking at the ceremony, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe spoke of the "inhumanity of nuclear weapons" but made no mention of Japan's own wartime past.

“The anniversary of the bomb being dropped has a very significant meaning for Japanese people to develop self-awareness as victims of the war,” said Hiroshi Tanaka, professor emeritus at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo. “That makes it very difficult on such a day to become aware of the other side, as a perpetrator.”