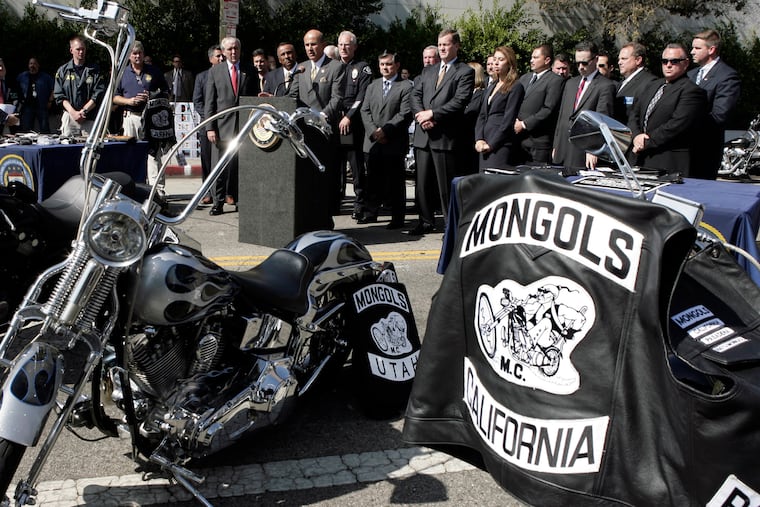

Calif. judge lets Mongols biker gang keep its trademark logo

A California federal judge has refused to order the Mongols motorcycle gang to forfeit its trademarked logo, delivering a blow to prosecutors.

LOS ANGELES (AP) — A California judge delivered a blow Thursday to a decadelong effort by federal prosecutors to strip the Mongols motorcycle gang of its trademarked logo, ruling such a move would be unconstitutional.

U.S. District Judge David O. Carter in Santa Ana nullified a first-of-its-kind jury verdict that would have given the government control of the logo — a Mongol warrior astride a chopper-style motorcycle — and two other trademarks.

Ordering forfeiture of the trademarks would violate the First Amendment rights to freedom of association and Eighth Amendment protections against excessive penalties, Carter said.

"The collective membership mark acts as a symbol that communicates a person's association with the Mongol Nation, and his or her support for their views," Carter wrote. "Though the symbol may at times function as a mouthpiece for unlawful or violent behavior, this is not sufficient to strip speech of its First Amendment protection."

Mongols attorney Joe Yanny said the ruling was a big deal for the bikers and he criticized prosecutors for wasting millions of dollars chasing “an impossible dream by some government guy who had no respect for the constitutional rights he might be trampling.”

"It's an attempt at collective guilt, which has never been the law here in this country," Yanny said. "You don't hold people guilty or punish folks simply because they know people that may be related in some fashion to people who are alleged to have done something wrong."

Prosecutors were disappointed with the ruling and may appeal, said Thom Mrozek, spokesman for the U.S. attorney.

Prosecutors had successfully argued before a jury that the logo was core to the identity of the Los Angeles area-based gang responsible for drug dealing, beatings, and murder. They argued that bikers wore the badges like armor to intimidate.

The January verdict appeared to conclude a 10-year quest that began after agents with the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives infiltrated the gang and 77 members were convicted of racketeering.

In January, the jury found the Mongol Nation entity guilty of racketeering and said the group's trademarked patches could be forfeited.

While Carter affirmed the convictions, which could carry fines at sentencing in April, he refused to give prosecutors what they had long sought.

In announcing charges in 2008, prosecutors said a forfeiture order would allow any law enforcement officer to stop a gang member and "literally take the jacket right off his back."

Prosecutors appeared to dial back that assertion, claiming in court papers that forfeiture was "merely a procedural step divesting the Mongol Nation of its legal rights to enforce exclusive use of the symbols." But Carter dismissed that argument as disingenuous.

"The government has lost credibility when it now suggests the sole purpose of more than a decade of prosecution is only to limit the Mongol Nation's ability to bring infringement lawsuits against other entities," Carter wrote.

Marsha Gentner, a trademark lawyer in Washington, said she was puzzled by what the government hoped to accomplish.

Under trademark law, the U.S. could prevent others from using the Mongols’ logos or name. They could potentially auction the rights to the trademark, though it was questionable who pay for it. If they did nothing with the trademark, it would eventually be considered abandoned and someone else could snap it up.

"This whole idea of seizing the mark," Gentner said, "it just was not well thought out."

The Mongols was founded in a Los Angeles suburb in 1969. The group is estimated to have more than 1,000 riders in chapters worldwide.

Yanny described the Mongols as a club that doesn’t tolerate criminal activity. He said the government targeted the group because of its large Mexican American population.

Former pro wrestler and Minnesota Gov. Jesse Ventura testified for the defense, saying he neither committed crimes nor was told to do so when he was a Mongol in the 1970s.

Prosecutors won the convictions after detailing violence that included the killing of a Hells Angels leader in San Francisco, a Nevada brawl in 2002 that left members of both clubs dead, and the killing of a Pomona policeman while raiding the home of a Mongols member in 2014.