Netflix’s ‘Meltdown: Three Mile Island’ tells the history of the infamous nuclear plant accident. Here’s how we covered it.

“We’re talking about a story where there’s a possibility here of the East Coast being contaminated with radiation,” said producer Carla Shamberg.

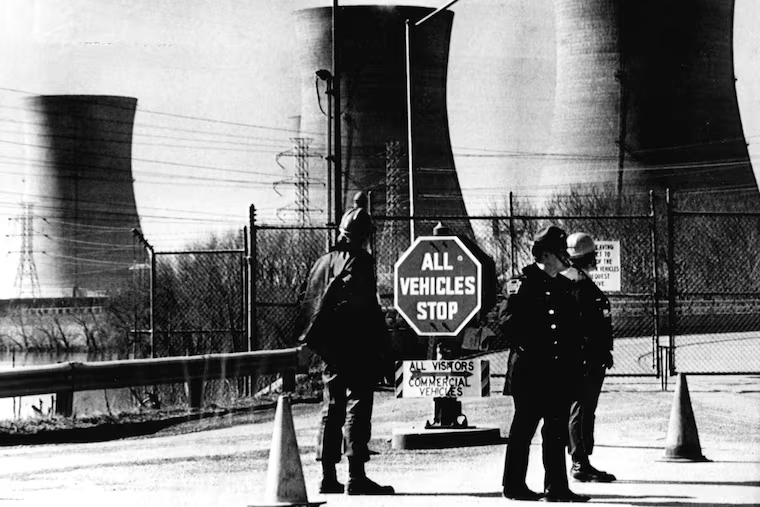

More than 40 years ago, central Pennsylvania was the site of what is considered the worst nuclear accident in the United States: the partial meltdown of Three Mile Island.

Located on the Susquehanna River about 10 miles outside of Harrisburg — about 90 miles from Philadelphia — Three Mile Island created enormous fear and was a huge blow to the nuclear power industry, which, in many ways, still hasn’t recovered.

With the release of Meltdown: Three Mile Island on Netflix, director Kief Davidson and executive producer Carla Shamberg’s four-part documentary delves into the incident and its aftermath, as well as the whistleblower who shed light on the unsafe cleanup of the plant after its partial meltdown.

“We’re talking about a story where there’s a possibility here of the East Coast being contaminated with radiation,” said Shamberg, whose credits include work as a producer on Erin Brockovich. “”It was an important story that had never been told.”

As a result, Davidson said, younger generations may have never heard of the calamity, or the lessons its story might hold.

“There’s an opportunity to talk to a younger audience that is completely unaware of what happened,” he said. “Even those that did know about Three Mile Island may only know the very basics.”

In 1980, the Inquirer won a Pulitzer Prize for local or spot news for its coverage of the incident. So, we took a trip back into our archives to see how the Inquirer and Daily News covered Three Mile Island, from the incident itself up to the plant’s ongoing decommissioning. Here is what we found:

The immediate aftermath

The partial meltdown of Three Mile Island’s Unit 2 started at 4 a.m. on March 28, 1979, when, according to an Inquirer report from that day, a “malfunction….caused a slight leakage of radiation into the atmosphere,” forcing a shutdown and evacuation of the facility. The reactor had just gone online in December 1978.

State officials, however, were not notified of an issue until about 7:45 a.m., at which point they declared a “general emergency” — the first ever declared at a nuclear reactor, according to an Inquirer report. A spokesperson for plant operator Metropolitan Edison, said at the time that he had “”no idea what caused it or why — if there was a delay.” Some local municipalities reported not being informed of an issue until 10 a.m. or later.

At the time, Lt. Gov. William Scranton called the incident “minor,” and said that “there is and was no danger to public health and safety,” but nearby homes were reportedly evacuated. A spokesperson for Metropolitan Edison Co., meanwhile, said that there was “no measurable release of radiation into the atmosphere.”

By that afternoon, Scranton told reporters that the problem was more complex than representatives from Met Ed led state officials to believe. Gov. Dick Thornburgh would later urge the evacuation of pregnant women and small children living within five miles of the plant, and suggested that anyone living within 10 miles stay indoors to avoid potential exposure to radiation.

“I am very skeptical of any one set of facts,” Thornburgh said.

Confusion continues

By March 30, state officials said that people living with five to 10 miles of the plant might have been exposed to as much as 100 millirems of radiation — about 10 times as much exposure as officials from Met Ed estimated. The average level from background sources is 100 to 120 millirems per year, the Inquirer reported at the time.

Additional low-level radiation continued to be released into the atmosphere, but federal officials said that a total meltdown at the reactor was not likely, and that there was no “imminent danger” of a public health threat, the Daily News reported three days after the incident began. But by April 2, a “hydrogen bubble” had formed at the top of the reactor, threatening the possibility of a meltdown — a fear that ultimately was avoided when the bubble began shrinking.

Fear and confusion, however, continued for years. Locals were concerned that with crystallized radioactive iodine falling to the ground, dairy cattle could eat contaminated grass, leading to contaminated milk (officials, however, said that most cattle were “being grain-fed” at that time). And reports indicated that radiation had been spread over a 16-mile radius from the plant, impacting at least four Pennsylvania counties.

Even the local media was driven into a panic, with KYW TV and KYW Radio putting up a sign in their office, then at 5th and Market Streets, requiring all radio and TV crews personally covering the story to be check for radiation with a Geiger counter, according to a Daily News report.

A hero emerges

By March 1983, the billion-dollar cleanup was well underway, and being led by the Bechtel Corporation. But a senior startup engineer at Bechtel, Richard Parks, then 31, made headlines alleging that Bechtel and plant operator General Public Utilities were taking safety shortcuts.

Parks, the protagonist of the Netflix doc, became a whistleblower after working with the Government Accountability Project to file a 56-page affidavit with the U.S. Department of Labor regarding the safety issues. In his affidavit, the Inquirer reported, Parks said his Middletown apartment had been burglarized, with thieves looking for papers. That burglary, Parks says in the documentary, prompted him to go public.

The centerpiece of Parks’ affidavit, the Inquirer reported in 1983, were concerns over what was called a “polar crane” — a piece of equipment at the top of the reactor that would be used in the cleanup. The issue, Parks said, was that the crane was damaged during the initial accident, and needed to be refurbished and tested to ensure its safety — and that he had been harassed by the company and relieved from a number of duties for his concern. Bechtel, meanwhile, issued a statement saying that the cleanup was being “conducted with safety as the number one concern.”

After filing the affidavit, Parks was suspended indefinitely with pay — a move that prompted him to accuse Bechtel of using “Gestapo-like tactics” to silence him. That suspension, which Bechtel said it pursued to “insulate” Parks from apparent harassment, lasted until May 1983, when the U.S. Department of Labor ordered the company to reinstate Parks. They appealed, and Parks remained suspended for several more months.

In August 1983, the Inquirer reported, Parks was allowed to return to work — but not at Three Mile Island. Instead, he accepted a similar job at a coal-gasification project in Southern California. Parks’ attorney told the Inquirer that he would withdraw his complaint with the Labor Department. Six months later, Parks was fired.

Plant operator indicted

Parks’ role as whistleblower, however, did impact the cleanup at Three Mile Island, as well as Met Ed. In November 1983, the Inquirer reported, a federal grand jury accused the company of routinely falsifying tests showing whether excessive water was leaking from the cooling system, and that they systematically destroyed records of those tests.

It was the first time that criminal charges were brought against a utility holding a license for a nuclear plant, the Inquirer reported. The 11-count indictment came more than four years after a former control room operator, Harold W. Hartman Jr., told investigators that he and others regularly fudged leak rate tests in the months before the accident at the direction of supervisors.

Ultimately, Met Ed plead guilty to falsifying records, and was ordered to pay a $45,000 fine and create a $1 million fund to help clean up the plant. That marked the first prosecution of a utility under the Atomic Energy Act, according to a February 1984 Inquirer report.

The end of Three Mile Island

While Three Mile Island’s Unit 2 went down for good following the 1979 partial meltdown, its corpse has sat at the site for decades. But in July 2019, EnergySolutions Inc. announced that it would acquire Unit 2 in order to decommission and dismantle it.

The sale was completed in December 2020, according to the company. But, as the Inquirer reported in 2019, it’s not clear when the decommissioning will be complete — though, under federal law, plant operators have 60 years to clean up nuclear energy sites after plants close. TMI-2 Solutions, a subsidiary of EnergySolutions, estimates that the process will be complete by 2037.

Unit 1, meanwhile, was not taken out during the 1979 incident, and remained operational until Sept. 20, 2019, when it was disconnected from the power grid, bringing an end to its 45-year run as a power producer. Exelon Generation, which owns Unit 1, announced in 2017 that it would close the reactor down, the Inquirer reported.

“Today marks the end of an era in Central Pennsylvania,” said Mike Pries, a Dauphin County commissioner, when the power station shut down. “It’s a difficult day for the community, for the county, and for all of Central Pennsylvania.”

Like with Unit 2, Unit 1′s decommissioning is in process. Overall, it will take an estimated $1.2 billion and 60 years to complete, putting its finish date sometime in 2079, the Inquirer reported.