N.J. sending teachers to visit trans-Atlantic slave sites to teach black history in public schools

New Jersey wants its 1.1 million public school students to learn black history year-round. A new initiative will send teachers to trans-Atlantic sites associated with the slave trade to better prepare teachers.

New Jersey public school teachers will get to travel to trans-Atlantic sites associated with the slave trade to learn how to better teach black history — not just in February but year-round — to comply with a decades-old state mandate.

The initiative was announced Friday as a new program under the state’s Amistad law, which requires all public schools to teach African American history. The mandate was established under a 2002 law signed by then-Gov. Jim McGreevey but has not been widely implemented.

It was the brainchild of Jacqui Greadington, a retired East Orange music teacher turned activist who wants to change how black history is taught. She got the idea after a visit to Ghana that she said "changed my life forever.”

“There are people who have no clue about the value of the African American story,” Greadington said.

» READ MORE: Slave auction historical marker unveiled near Camden waterfront, where hundreds were brought and sold

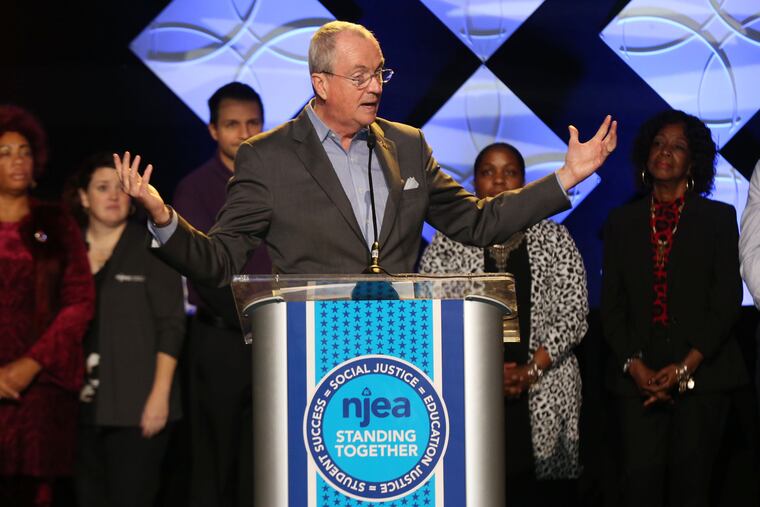

Gov. Phil Murphy joined state education officials to unveil the program at a news conference in Atlantic City at the annual gathering of the New Jersey Education Association. The teachers’ association will pick up the cost for the program, initially about $75,000 a year.

“We all know that the work of racial justice is hard, but it’s far too important to let that stop us,” NJEA president Marie Blistan told hundreds of attendees. The convention included a keynote address by scholar and activist Cornel West.

State Education Commissioner Lamont O. Repollet said the state plans to better ensure that districts embed African American history into their lesson plans. Beginning this school year, districts that fail to comply can lose points in their state evaluation, he said.

“This work is personal for me,” said Repollet, New Jersey’s first black education chief.

New Jersey and Pennsylvania require history to be taught, but districts decide the content of their courses. In Philadelphia, a course in African American history, including the civil rights movement, is a graduation requirement.

» READ MORE: Penn students join dining-hall workers to condemn lack of Black History Month observance

The Amistad bill calls for New Jersey’s schools to infuse African American history into the K-12 social studies curriculum. Every summer, the Amistad Commission hosts a 10-day workshop for about 150 educators, providing training and resources to help them in the classroom, but more is needed to ensure that black history is adequately taught, said Stephanie James Harris, the commission’s executive director.

“All of our stories need to be told,” said Harris. “All of our narratives are important to American history.”

The Amistad was a ship carrying 53 Africans who had been kidnapped and sold into the Spanish slave trade in 1839. The slaves revolted, killing most of the crew. The ship ran aground near Long Island, and the government seized the Amistad and its passengers as cargo. The U.S. Supreme Court ordered their release.

About 20 educators will be selected for the Amistad journey program to visit sites next summer, said Ed Richardson, NJEA executive director. In the first year, teachers will probably visit U.S. slavery sites, such as Jamestown, Va., Charleston, S.C., and New Orleans, and later include a trip to Ghanam where Africans walked through the “door of no return” at Cape Coast onto slave ships.

» READ MORE: Philly renames parts of Market and Sixth Streets in honor of founding fathers, black history

The Amistad journey program is modeled after one that sends educators to Holocaust sites in Europe. New Jersey passed a law in 1994 requiring Holocaust and genocide education in public schools and talk about bias, prejudice, bigotry, and bullying.

Holocaust survivor Maud Dahme, a member of the Holocaust Commission, applauded plans to send educators to slave trade sites. She came to the United States in 1950 at 14 and was surprised to learn how black people were treated.

“I had no idea of what was going on in this country racially. It was shocking," she said.

A 2018 study by the Southern Poverty Law Center, the antidiscrimination group , found that schools are not adequately teaching the history of American slavery and educators are not adequately prepared to teach it. The study also found that textbooks lack enough information about slavery.

According to the Montgomery, Ala.-based center, only 8% of high school seniors surveyed could identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War. Most didn’t know an amendment to the U.S. Constitution formally ended slavery. Fewer than half correctly answered that slavery was legal in all colonies during the American Revolution.