Former federal judge in Camden recalls days as a civil rights activist in Jim Crow South as ‘the right thing to do’

Joel B. Rosen rarely talks about his Alabama experience, but spoke in advance of the 53rd anniversary of James Meredith’s “march against fear.”

When civil rights activist James Meredith set off on his second march in the Jim Crow South more than 50 years ago, a young community activist who would later become a judge in South Jersey was right with him.

The experience would shape the career of Joel B. Rosen, spanning more than 30 years as a lawyer, a federal prosecutor, a deputy state attorney general, and a federal magistrate judge in Camden.

Rosen dropped out of college during his junior year in 1966 to join the civil rights movement. He trained in Atlanta and was sent to Huntsville, Ala., with another volunteer, Joe Murphy. They were the first activists dispatched there by VISTA, created by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 as a domestic version of the Peace Corps.

”It was life-changing for me in many ways,” Rosen said. “It was just the right thing to do.”

Rosen, who rarely talks about his time in the South, shared his experiences as the 53rd anniversary approaches for Meredith’s long “march against fear” through Mississippi in June 1967, to encourage blacks to vote. Meredith integrated the University of Mississippi in 1962.

Huntsville, in the foothills of the Appalachians, was not an epicenter of the civil rights movement like Selma, Montgomery, or Birmingham, where there were bloody marches and clashes with police. But it had its own racial problems.

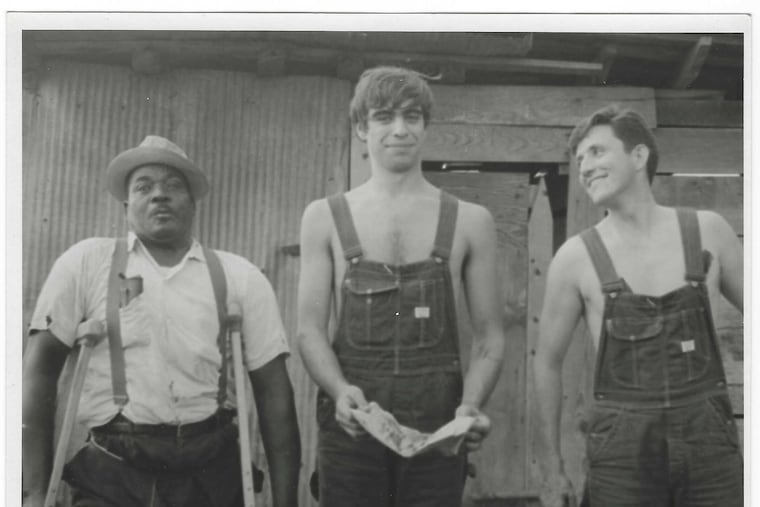

Rosen and Murphy, of Jersey City, N.J., arrived in Huntsville in 1967. Rosen, then 20, had grown up in New Canaan, Conn., in the only Jewish family in town (his mother was Italian). He had never seen a “colored only” sign or interacted with blacks.

They helped blacks register to vote, recruited black students to register to attend white schools, organized a unit of black maids to demand fair wages, started a coal co-op to provide heat, and built dozens of outhouses. They marched, too, often under the watchful eyes of the Ku Klux Klan.

Violence was common, and Rosen learned how to fire a weapon as a precaution, remembering the murders of activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi in 1964.

“It was not making people happy down there,” recalled Rosen, 73, who lives in Camden County. “It was tough times.“

Historians believe Hunstville was more progressive than other Southern cities because it was home to the Marshall Space Center and was a base of the NASA space program. Engineers were refusing to move there because of racial unrest, and the town could have lost millions in federal funding if the government moved the program, which developed the Saturn launch vehicles.

Freedom Riders, a group of 13 activists who traveled throughout the South in 1961 to integrate bus terminals, helped organized sit-ins at “whites only” lunch counters in Huntsville and elsewhere. Huntsville was the first town in Alabama to integrate its public schools, in 1963.

“We changed the country and brought freedom to black people,” said Hank Thomas, 79, of Atlanta, one of the three surviving original Freedom Riders. “I am very, very proud.”

Thomas was aboard a bus that was surrounded by an angry mob in May 1961 when it arrived in Anniston, Ala., about 100 miles from Huntsville. The bus was firebombed and the Freedom Riders escaped as it burst into flames. They were beaten by the mob.

Despite fear of possible violence, Rosen and Murphy joined Meredith on June 29, 1967, the sixth day of his march to Jackson, Miss. Unlike Meredith’s march the year before, which had drawn thousands after a sniper shot Meredith with buckshot, the second one attracted a smaller crowd. A New York Times article noted that the VISTA volunteers were among three white youths on the march. The activists took “side trips if we thought there was a good march,” Rosen said.

While in Huntsville, Rosen met his future wife, Kari, a young activist. Her mother, Estelle Kay, was involved in the movement and invited Rosen to their home for dinner. Kari was captivated by the dashing Northerner.

”I was absolutely in awe of him,” recalled Kari, 69, a retired special education teacher.

Rosen left Huntsville in early 1968 to finish his degree in sociology at Colgate University. He moved to South Jersey in 1970 to attend Rutgers School of Law in Camden.

Looking back on his experiences more than 50 years ago, Rosen downplayed his time in Huntsville: “I did what I could, but I was no hero,” he said.

Jane DeNeefe, co-director of the Huntsville African American History Project, said Rosen “helped set a tone for responsible social activism in Huntsville that continued to reverberate after he was gone."

Rosen retired from the bench in 2006 as a U.S. magistrate judge in Camden after nearly 20 years. He previously was an assistant U.S. attorney and a deputy state attorney general. He currently is senior counsel in the Cherry Hill firm of Montgomery, McCracken, Walker & Rhoads.

“His commitment to civil rights for all is longstanding, genuine, heartfelt, and has few equals in our courts,” said U.S. District Judge Robert Kugler, a longtime friend.