Sharing meals brings families together, even in prison. Doing without has strained ties.

Access to outside food on certain visits was a perk so valued its elimination was a major trigger for the Camp Hill prison riots in 1989.

Constraints, they say, breed creativity. At the least, they explain the advent of the prison ravioli sandwich — a pile of homemade, ricotta-filled pasta, doused in red gravy and wedged unceremoniously between two slices of bread.

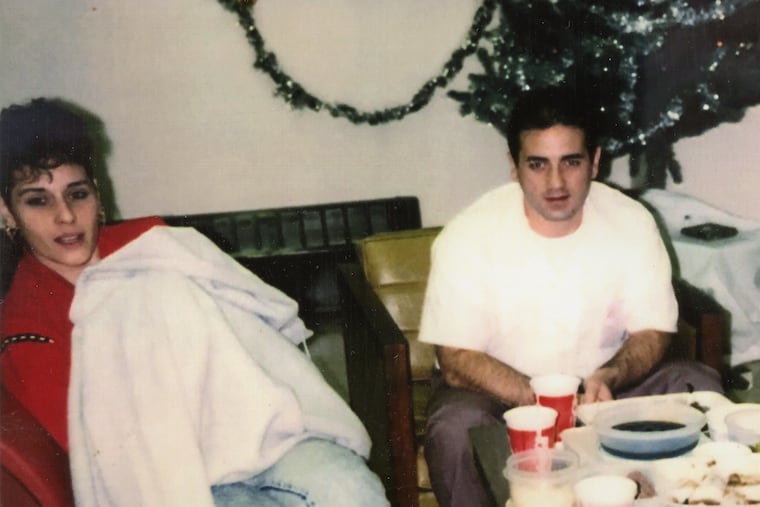

“You were allowed to take in one sandwich per visitor,” explained Marcie Marra, 53. So, she had to innovate. She would lovingly tote such concoctions from her home in South Philadelphia to State Correctional Institution (SCI) Dallas, where her brother, Richie, was then incarcerated.

The Anything, As Long As It’s Between Bread epoch (which the Department of Corrections did not confirm was an official policy) was just one chapter in the evolution of prisoners' access to one of the most basic and universal human impulses: to break bread with loved ones.

Access to outside food on certain visits was a perk so valued its elimination was a major trigger for the Camp Hill prison riots in 1989. Today, those homemade spreads are a distant memory, replaced with soggy sandwiches purchased at vending machines that, meager though they may be, remain a central part of how families connect and show one another hospitality.

But those vending machines have been offline at most Pennsylvania state prisons for months now, as part of a wide-ranging security crackdown that also includes the diversion of postal mail to a processor in Florida to be scanned and digitally forwarded, and the delivery of books to a central processing facility.

The state Department of Corrections announced what it called a 90-day moratorium on food vending on Sept. 5 pledging to restore the machines after body scanners were installed that could detect any contraband on inmates leaving the visiting room.

By way of justification, the department published a copy of an intercepted letter advising a female visitor to smuggle a sealed packet of drugs into a cup of chocolate milk that the inmate could then swallow and sneak into the institution.

“Visiting was, and continues to be, a primary avenue for drug smuggling," DOC spokesperson Amy Worden said in an email. Just over the last month, she said, the DOC has intercepted drugs, including synthetic cannabinoids, suboxone, and oxycodone, in and around visiting rooms on six different occasions.

Today, food vending machines have been reinstated at seven out of 25 visiting rooms, with more on the way, she said.

But the interim period has been challenging, according to the Pennsylvania Prison Society, which runs bus trips to most state prisons. Its ridership declined 28 percent in October compared with a year ago. Many who canceled visits cited lack of food as a key reason. After all, many prisons are hours away, and visitors must sometimes wait 60 minutes or more to be admitted.

“If you are elderly or diabetic or have a small child, it is impossible now for you to visit your loved one,” said Claire Shubik-Richards, who heads the nonprofit. The DOC has said visitors with medical conditions can request exemptions — and Prison Society volunteers have offered to submit such requests on behalf of visitors who’ve canceled visits over the food policy.

“No one has taken us up on it, though we’ve offered to seven or eight people,” she said. “I think that just speaks to how exhausting and difficult it is for a family to go and visit.”

Lorraine “DeeDee” Haw, whose son has been incarcerated 22 years, has not been to see him at Smithfield prison, a four-hour drive from her home in Kensington, since August. (Vending machines there were recently restocked, according to the Prison Society, but Haw is waiting for her son to confirm it.)

“I want to take my son’s first granddaughter,” she said, “and because of the food situation I can’t. ... She’s only 5. I can’t make her suffer like that."

Researchers have linked prison visitation to significant reductions in recidivism: An analysis by the Minnesota Department of Corrections found that visits reduced the risk of felony re-convictions by 13 percent, and correlated with a 25 percent decline in technical parole violations.

Home-cooked meals have at various times been a significant part of that. The records of Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia show policies that shifted over the years, at times allowing visitors to bring in cards and flowers for holiday visits. In 1896, Christmas packages filled with “eatables” were returned to sender, according to wardens' logs. But by 1917, a former inmate sent “candy, cake and peanuts,” according to a prison newspaper. (Today, prisoner care packages, ordered through contracted online commissaries, have fueled an entire industry.)

Worden, the DOC spokesperson, said that the department believes in the importance of family visitation but that outside food had never been allowed in prison visiting rooms.

Still, those who visited the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections in the 1970s and ’80s remember toting with them multicultural banquets. Haw recalled visiting an older brother at the now-shuttered State Correctional Institution (SCI) Graterford, packing rice and beans and homemade cakes. “Then, out of the clear blue sky, that stopped.”

At SCI Camp Hill, inmates took eight correctional officers hostage and set numerous fires in 1989 — an infamous, seven-hour riot that led to numerous security reforms across the prison system. One of the reasons cited as igniting the riot was a new rule barring visitors from bringing homemade food, out of concern it was a source of contraband.

John Pace, who was incarcerated at Camp Hill when the riot occurred, said outside food was a perk valued during the holidays and during special outdoor family visits in the summertime.

“You’d be able to sit around with a tent over us and the picnic tables, and be with your family, and the kids running around,” he said. His mother, since deceased, would bring fried chicken and collard greens. “It gave you that sense of being home, that sense you were connected to your family.”

To prisoners, the end of all that felt like punishment.

But it was part of a nationwide trend. A 1996 article in the journal Federal Probation noted several prison systems, including in the federal Bureau of Prisons, had recently barred visitors from bringing food, as part of a trend toward “no-frills” prisons. “This amenity is typically eliminated because of the staff time required to search the food for contraband,” the article noted.

Sitting across from a row of barren vending machines in the hushed visiting room of SCI Mahanoy recently, Frank Grazulis, a juvenile lifer from South Philadelphia who was convicted of a fatal stabbing in 1990 near South Street, cast his mind back to a different era.

“Back when I first came to prison, they really emphasized family ties. [SCI] Dallas was famous for having food visits, and I remember picnics on the baseball field in [SCI] Huntingdon," he said. He recalled the holidays as one big Italian feast, visitors and prisoners all stuffing themselves with pasta and getting tipsy on rum-soaked baba cakes.

“Slowly, things started getting taken away,” he said. "Now, in the past 10 years, it’s almost like a feeling of discomfort in the visiting room.”

Vending-machine sandwiches, heated in a microwave, became what passed for home cooking.

Still, families hover near the machines, carefully selecting the right meal, then cooking it just so — for instance, microwaving the contents of each cheesesteak separate from the napkin-wrapped hoagie roll.

Marra, whose brother Richie was 22 when he shot another man in a fight in a nightclub in 1986, knows these aren’t fancy meals. But her family still looked forward to them.

On her brother’s birthday each year, she used to get a piece of cake from the vending machine, arrange pretzel sticks like candles, and sing until he was thoroughly embarrassed. “That’s something we couldn’t do this year,” she said.

“It sounds crazy, but to have a cup of coffee or a piece of a cake is a big thing."