American bishops face new judgment over sexual abuse after decades of failed reforms, cover-ups

The sexual abuse reforms America's bishops promised in 2002 failed to cover one key group of clerics: themselves. Is a reckoning underway?

Failure at the top

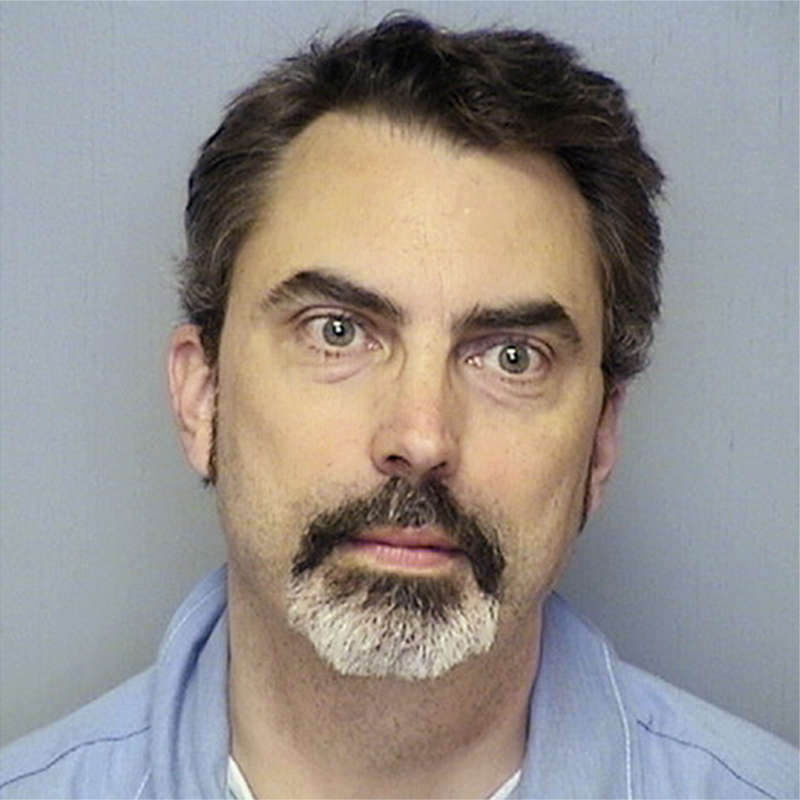

Bishop Robert Finn wasn’t going anywhere.

He never alerted authorities about photos of young girls’ genitals stashed on a pastor’s laptop. He kept parishioners in the dark, letting the priest mingle with children and families. Even after a judge found the bishop guilty of failing to report the priest’s suspected child abuse — and after 200,000 people petitioned for his ouster — he refused to go.

“I got this job from John Paul II. There’s his signature right there,” Finn had told a prospective deacon shortly after the priest’s arrest in 2011, pointing to the late pontiff’s photo. “And that’s who I answer to.”

Sixteen years after the clergy sexual-abuse crisis exploded in Boston, the American Catholic Church is again mired in scandal. This time, the controversy is propelled not so much by priests in the rectories, as by the leadership, bishops across the country who like Finn have enabled sexual misconduct or in some cases committed it themselves.

More than 130 U.S. bishops – or nearly one-third of those still living — have been accused during their careers of failing to adequately respond to sexual misconduct in their dioceses, according to a Philadelphia Inquirer and Boston Globe examination of court records, media reports, and interviews with church officials, victims, and attorneys.

At least 15, including Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington who resigned in July, have themselves been accused of committing such abuse or harassment.

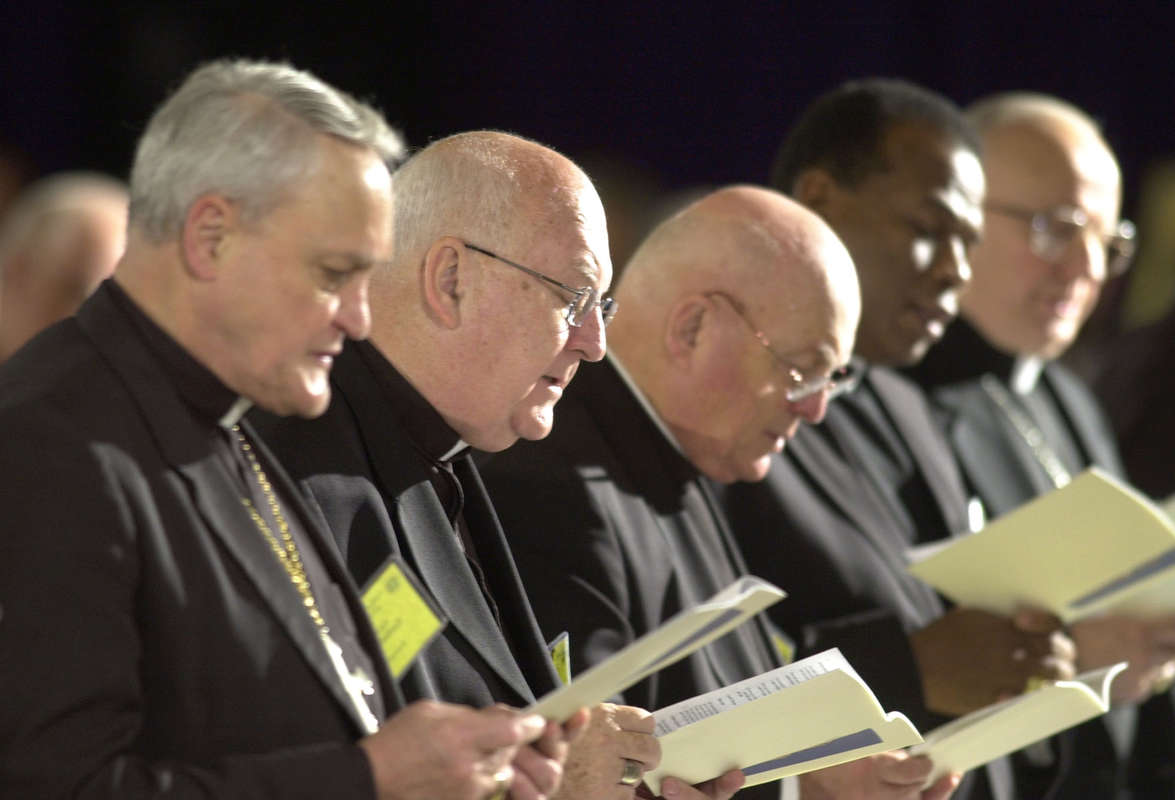

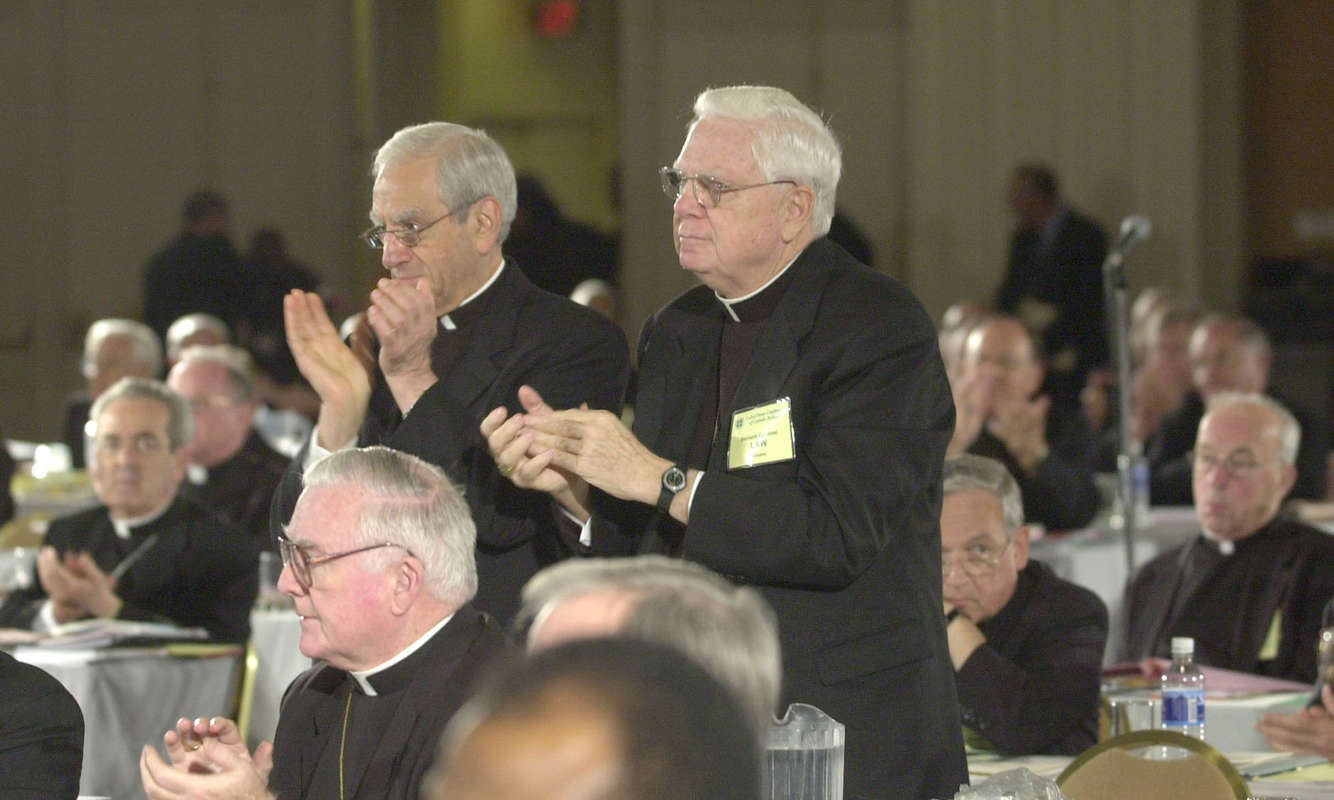

Most telling, the analysis shows that the claims against more than 50 bishops center on incidents that occurred after a historic 2002 Dallas gathering of U.S. bishops where they promised that the church’s days of concealment and inaction were over. By an overwhelming though not unanimous vote, church leaders voted to remove any priest who had ever abused a minor and set up civilian review boards to investigate clergy misconduct claims.

But while they imposed new standards that led to the removal of hundreds of priests, the bishops specifically excluded themselves from the landmark child-protection measures. They contended that only the pope had authority to discipline them and said peer pressure — public or private shaming they euphemistically called “fraternal correction” – would keep them in line.

It hasn’t.

About this Story

Boston and Philadelphia have been ground zero for the Catholic clergy sex abuse scandal — both cities have endured years of church investigations, allegations, prosecutions and lasting scars. Now, amid a rising tide of revelations about misconduct by U.S. bishops, the Inquirer and Globe pooled their resources for a deeper look at the crisis. Reporters from the two newsrooms visited nine states, conducted scores of interviews, and reviewed thousands of pages of court and church records to produce this report. Funding for the effort came from the Lenfest Institute for Journalism.

Bishop accountability has proved a contradiction in terms; resistance and indifference remain all too common. Even some of the bishops who wrote the 2002 reforms would themselves be accused of enabling or ignoring abuse. And the chairwoman of the new civilian board overseeing compliance with the reforms quickly despaired of the seriousness of the bishops’ commitment, saying, in a 2004 letter not previously reported, that their pledge to change “appears to be nothing more than a common fraud.”

In short: The price of reform has been paid, visibly, by parish priests. Their bosses, however, have been largely spared.

Meanwhile, allegations have piled up. In late October, a former assistant to Bishop Richard Malone of Buffalo accused him of covering up abuse after releasing hundreds of secret documents that showed how Malone repeatedly mishandled cases.

Drafting a New Policy on Problem Priests, While Facing Criticism on Their Past Actions

Six of the eight bishops on the committee that drafted the Catholic Church’s child-protection policies in Dallas in 2002 had faced criticism for their records on sexual abuse in the past.

West Virginia’s longtime bishop, Michael Bransfield, resigned in September after at least three claims emerged that he had sexually harassed younger priests. In 2015, Bishop Michael Hoeppner of Minnesota allegedly forced a deacon-in-training to retract his own accusations of being abused by a priest when he was a teen.

But there have been few consequences. The Vatican has allowed bishops who have faced credible allegations to slide quietly into church-funded retirement. Those still in power take orders only from Rome.

“The bishops simply do not have anyone looking over their shoulder,’’ said the Rev. John Bauer, a Minneapolis pastor. “Each bishop in his own diocese is pretty much king.”

The damning grand jury report in Pennsylvania in August, which chronicled hundreds of instances of clergy sex abuse over decades, many kept hidden by church officials, has sparked new scrutiny. Now, the U.S. Justice Department and at least 13 attorneys general — from New Mexico to Missouri to Washington, D.C. — have launched investigations, no longer content to let the church police itself. In Wyoming, an 87-year-old retired bishop could face criminal charges after police reopened decades-old allegations of child sex abuse.

The stream of revelations has taken a toll on the faithful as well, many of whom were already turning away from the church. Less than 39 percent of Catholics reported attending Mass in the preceding seven days, down from 45 percent the previous decade, according to the most recent Gallup poll.

The nation’s bishops will convene in Baltimore on Nov. 12, confronting the question they failed to address in the last 16 years: How do they make themselves more accountable?

“This is the church’s #MeToo moment,” said Thomas Plante, a former lay adviser to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. “Why should you trust church leadership if the rules don’t apply to them?”

As the clergy sex-abuse scandal mushroomed from Boston across the country in 2002, engulfing scores of priests in allegations that they had abused children, some bishops seemed to grasp the urgency of the moment.

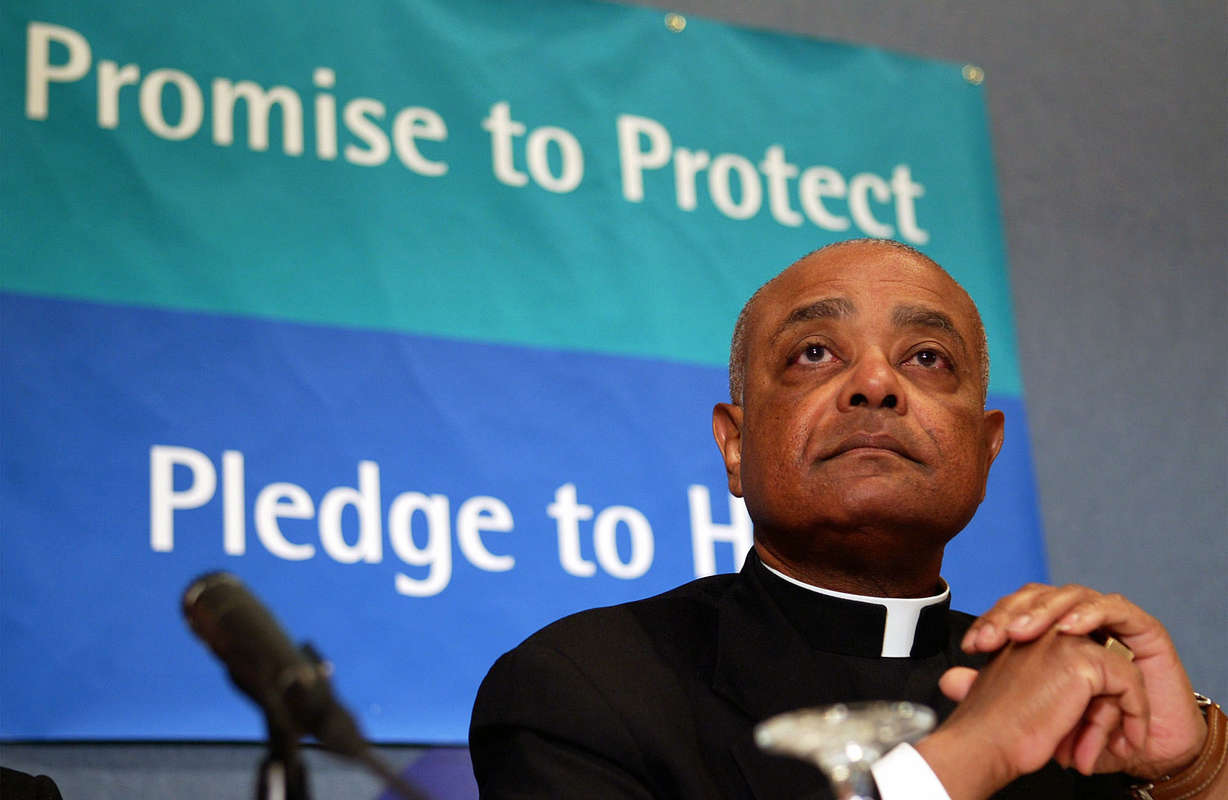

“The Catholic Church in the United States is in a very grave crisis, perhaps the gravest we have faced,’’ Bishop Wilton Gregory of Atlanta, who then led the conference, told his peers.

Gregory blamed bishops’ “arrogance” and “unchecked power.” He challenged them to develop new governing laws to better hold all clergy, including themselves, accountable.

On one level, they seemed to do just that. The leaders of the nation’s roughly 70 million Catholics vowed that no sexual predator would work in the U.S. church ever again.

But they carved out a critical exception in their zero-tolerance policy: Minutes from the 2002 conference show the policy had been drafted to apply to all “clerics,” including bishops. But, noting that as a group they lacked authority to investigate or discipline one another, Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua, then Philadelphia’s archbishop, led a push to limit the new strictures to “priests and deacons,” the records show.

(Bevilacqua would later be vilified in three grand jury reports over the next 15 years for repeatedly burying clergy sex-abuse claims and shuffling predator priests as a bishop in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.)

Other prelates who supported the exemption said they weren’t trying to escape responsibility. They just assumed that the Vatican would punish bishops for serious transgressions.

“I thought if I committed a crime against a young person or in any serious way violated my responsibilities that the Holy See would step in and take me out of office,” Archbishop William E. Lori of Baltimore explained this fall.

But the problems in Dallas ran deeper than a misplaced faith in the Vatican as a disciplinarian. The bishops were a deeply compromised group.

Of the eight-member committee assigned to draft what became known as the Dallas Charter, five had faced past accusations that they had mishandled abuse claims. Just months before the convention, the group’s leader, Bishop John McCormack of New Hampshire, stepped aside amid criticism for concealing the names of accused priests while he worked for Cardinal Bernard Law in Boston.

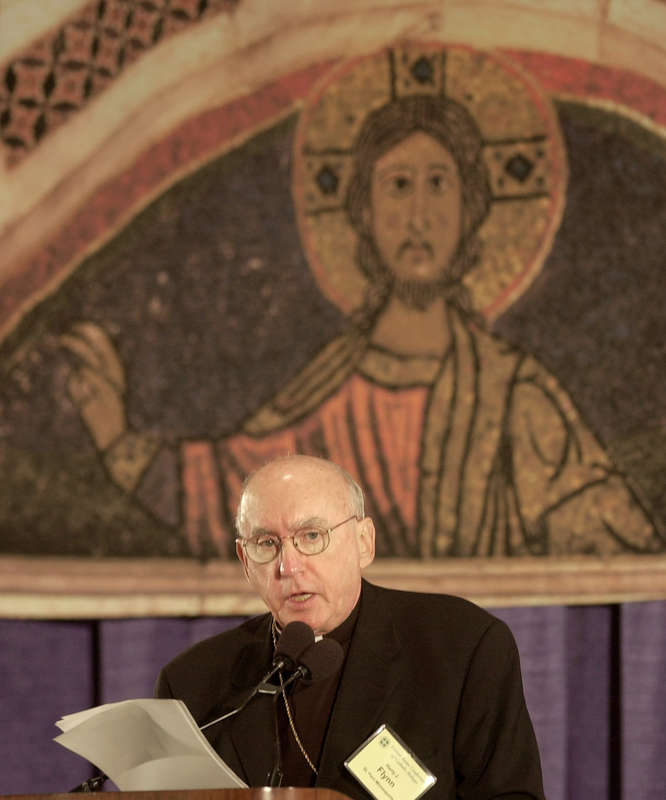

Archbishop Harry Joseph Flynn of St. Paul-Minneapolis was selected to replace McCormack, largely on the reputation he had earned for effectively handling the nation’s first clergy sex-abuse scandal in Lafayette, La. — the 1985 case of the Rev. Gilbert Gauthe, who had molested dozens of children.

But in the years that followed, Flynn, too, would be caught in the scandal’s undertow.

In 2014, a dozen years after Flynn had stood before a bouquet of microphones to trumpet the reforms, his words were being recorded again – this time in a legal deposition.

That day, Flynn repeated more than 130 times that he could not recall how he handled abuse cases during the 13 years he led his Minnesota archdiocese. Even a high-profile case that drew national attention — involving a priest who abused nine boys — had eluded his memory.

Flynn, then 81, attributed his answers to the forgetfulness of old age; critics saw them as evasive.

By the time Flynn faced the lawyer’s questioning, he had already made one appointment that proved fateful in revealing many more abuse allegations against priests. Before Flynn retired, he hired canon lawyer Jennifer Haselberger, who would later become an adviser to Flynn’s successor, John Nienstedt.

Some of the records that crossed her desk horrified her, she said: Reports of a priest with pornography on his computer. Another imprisoned for criminal sexual misconduct and theft. Warnings and concerns to Nienstedt that had been all but ignored.

“I saw the hierarchy just completely disrespecting on every level the needs of the people they were serving,” Haselberger said during an interview in St. Paul.

Consider the case of the Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer.

Flynn ordained Wehmeyer in 2001 despite concerns expressed by his seminary supervisors, who feared he was not up to the demands of being a priest, court records show.

Haselberger warned Nienstedt not to promote him. In 2009, the bishop ignored her advice, naming him pastor of two merged parishes.

The following summer, Wehmeyer sexually abused two brothers, 12 and 14, during a camping trip — assaults that eventually led to his conviction on molestation and child-pornography charges.

By that time, Haselberger had had enough.

“I think the psychological term would be nonstop moral distress,” she said in an interview. “You know what the right thing to do is, but the organization’s conditions do not allow you to do that.”

She quit in protest in 2013 and took her concerns to the office of St. Paul’s top prosecutor, Ramsey County Attorney John J. Choi.

In 2015, Choi’s office charged the archdiocese in a six-count complaint that alleged Nienstedt, Flynn, and a former vicar general had ignored Wehmeyer’s sexual misconduct and failed to protect children. Prosecutors cited “a disturbing institutional and systemic pattern of behavior” over decades at the highest levels of leadership in the archdiocese.

Nienstedt apologized and resigned 10 days later. Church officials ultimately settled the case with an admission that they had failed to protect children and an agreement to institute broad background checks for clergy and church volunteers. The criminal charges were dropped.

In a recent statement, Nienstedt insisted that he “took any warning about abusive priests very seriously.” The bishop also said, “The only case involving a priest abusing a minor on my watch was the Wehmeyer case, and we called the police as soon as we were made aware of the information.’’

Flynn, 85, declined to comment for this story.

His troubles might not be over. A 55-year-old woman contacted the bishop’s former diocese in Lafayette recently to inform it that its current judicial vicar, Msgr. Robie Robichaux, had sexually abused her, and that Flynn had done nothing to remove him from ministry. Instead, he agreed to pay her counseling bills for the near daily abuse she allegedly suffered as a teenager by Robichaux from 1979 to 1981, according to letters from church leaders the victim shared.

The woman reached out to Bishop Michael Jarrell in 2004, but Robichaux still remained. After she reached out to the diocese for a third time in September, Robichaux was placed on administrative leave.

“It only took 25 years and two cover-ups,” she told the Inquirer and Globe.

Almost as soon as the Dallas Charter was enacted, Anne Burke began questioning whether the bishops’ reforms were more about public relations than public remorse.

Burke, then a state appeals court judge in Illinois, stepped in to lead the National Review Board created to advise church leaders and ensure that local dioceses complied with the charter. At the same time, the bishops established review panels in each diocese — boards composed of community members, some even from law enforcement — to examine complaints about misconduct or sex abuse that came through the door.

The bishops still made final decisions on discipline or reassignments, but at least now the allegations would also be vetted by a group more loyal to the Catholics in the pews than the men at the altar.

Burke was in position to see where the new policy was working and where it decidedly was not. Between 2003 and 2004, she logged complaints from local board members — about bishops destroying records, concealing claims, and generally balking at the new rules they had just endorsed in Dallas.

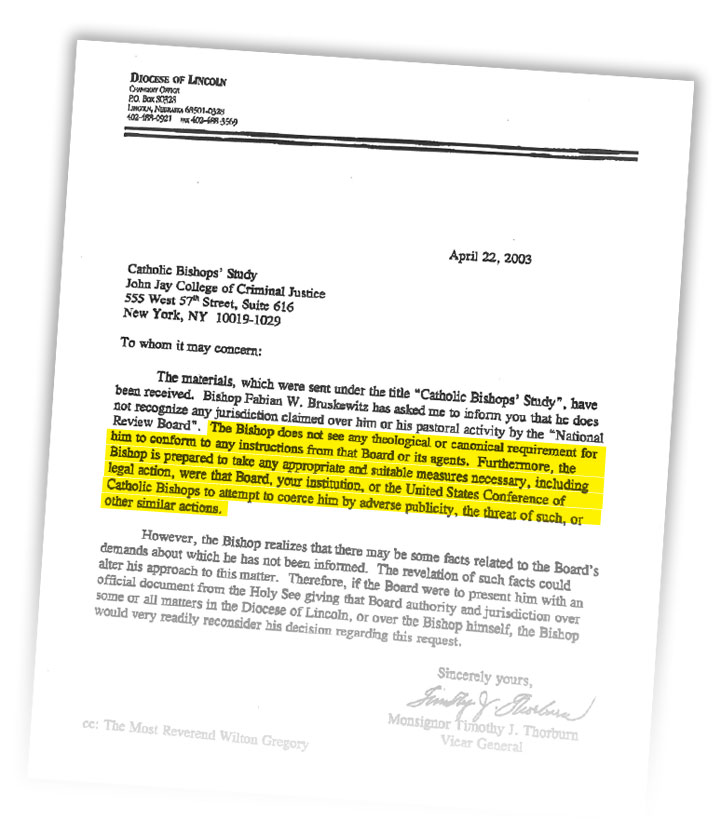

Bishop Fabian Bruskewitz of Lincoln, Neb., challenged the bishops’ authority to order an audit of his diocese and threatened to sue if he or it were publicly criticized. Cardinal Edward Egan of New York publicly disinvited Burke and fellow review board members from a 2003 charity dinner.

Challenging Civilian Oversight

The 2002 Dallas Charter included the establishment of a civilian-led National Review Board to advise bishops on child-protection policies and oversee a nationwide audit to ensure compliance with the charter’s goals. The following year, Bishop Fabian Bruskewitz of Lincoln, Neb., had a letter sent to the board, saying he didn’t recognize its authority and wouldn’t participate in the audits, threatening legal action. By 2004, Anne M. Burke, the head of the board, wrote to the Vatican, saying the reform pledged by the U.S. bishops “appears to be nothing more than common fraud.”

That same year, Cardinal Francis George of Chicago told them they were overseeing the “downfall of the church in America” and forwarded Burke complaints from other bishops who questioned the suitability of members of the review board, including former Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating, and Leon Panetta, the onetime White House chief of staff.

“They wanted any excuse to start picking us off,” Burke, now a state Supreme Court justice, said in an interview last month.

George, at that time, was letting a convicted sex abuser live in his mansion — a fact Burke and her colleagues discovered just hours after he had told them Chicago no longer had a clergy sex-abuse problem.

In 2004, Burke appealed to Rome for help. In correspondence to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger — the man who would become Pope Benedict XVI — Burke accused America’s bishops of acting as if they had “dodged a bullet.” She also expressed frustration over what she saw as a newfound confidence to flout reforms they had prominently backed barely a year before.

“At best, they are being very shortsighted,” Burke wrote in the letter. “At worst, we believe they were never truly serious about establishing safeguards for the protection of children and youth.”

Even church leaders admit it: One of the glaring gaps in the sex-abuse reforms is the lack of a system to report and investigate allegations against bishops.

It was obvious in the years between the first reports of Cardinal McCarrick’s misconduct — his sexual relationships with seminarians and younger priests — and his July resignation.

It has since become obvious, too, in how the church dealt with West Virginia’s longtime bishop, Michael Bransfield.

Raised in a family of prominent Philadelphia clerics, Bransfield had built a reputation as a reliable Vatican fund-raiser and spent two decades climbing the ladder at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington. In 2005, he was named bishop of the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston.

Two years later, church leaders in Philadelphia fielded a complaint from a man who said Bransfield had sexually abused him in the late 1970s, when he was a teen and the priest a teacher at Lansdale Catholic High School.

Cardinal Justin Rigali, then Philadelphia’s archbishop, quietly alerted law enforcement authorities, who deemed the case too old to be prosecuted. Rigali never shared the allegation with his local church review board — as was required by the zero-tolerance policy promulgated in Dallas — or announced it to the region’s 1.5 million Catholics.

Five years passed before the claim became public, and then only during an unrelated trial of a monsignor accused of helping the Philadelphia Archdiocese conceal the misconduct of predator priests. One witness testified that he had endured abuse decades earlier at the hands of one of Bransfield’s friends, an infamous Philadelphia priest named Stanley Gana, and that Bransfield knew about it.

In written statements issued by his diocesan spokesperson, Bransfield disputed that claim — and that he had ever abused anyone.

But the headlines added to what had been years of whispers in his West Virginia diocese of 78,000 Catholics, where Bransfield was reputed to have a fondness for young, attractive seminarians, among them some he promoted into positions typically reserved for more experienced clerics.

One priest recalled a dinner he and other then-seminarians attended with Bransfield at a Washington restaurant in the mid-2000s. The bishop, he said, hovered “unusually close” to another young student, even drinking from the same glass of wine.

“It made me really uncomfortable,” said the priest, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution. “I was thinking, ‘Was [this student] even old enough to be drinking?' ”

There were other ways, too, that Bransfield stood out in Wheeling, amid the hardscrabble hills of Appalachia.

His bishop’s mansion there boasted a personal chef, a 13-foot sunken bar, and a 100-square-foot wine cellar. He entertained around an ornate dining-room table, custom-built and shipped in from the United Kingdom. He ordered horses for a rural pastoral center so he could watch them out the window as he ate, according to visitors and diocesan staffers.

The bishop lived “like an Arab sheik,” said the Rev. Jim Sobus, a priest not longer in the diocese.

Still, few spoke up about Bransfield, perhaps because of his power.

“You take a vow of obedience to [your bishop],” said the Rev. Bekeh U. Ukelina, who served under Bransfield but is now on a leave of absence. “You implicitly understand a bishop can destroy you.”

Indeed, the concerns about Bransfield remained beneath the radar until a larger controversy engulfed the church, one that appeared to have emboldened alleged victims to come forward.

McCarrick’s resignation this summer — after decades of claims from accusers in New Jersey and New York — was a hallmark event, the ouster of the highest-ranking U.S. prelate, a cardinal, over sex-abuse allegations.

Soon after, at least three priests came forward with claims that Bransfield had subjected them to unwanted sexual advances and physical contact, according to one person familiar with the church’s ongoing investigation.

Officials have since set up a hotline to field complaints just about Bransfield; more than 75 calls have come in, alleging misconduct in West Virginia, Washington, and Philadelphia that stretches back decades.

Bransfield abruptly resigned in September, a few days past his 75th birthday, after what the U.S. Bishops Conference described only as accusations of “sexual harassment of adults.” Pope Francis appointed Lori, the Baltimore archbishop, to lead the investigation and take control of the Wheeling-Charleston Diocese.

Bransfield has been banned from returning to West Virginia. Reached on his cellphone weeks after his retirement, he declined to talk to a reporter.

“I’d rather not,” he said. “It’s probably about bishops.”

If the church has been slow to act against bishops accused of misconduct, the hope that public shaming could make them do the right thing has also fallen short. Pressure from fellow bishops — or what some dubbed “fraternal correction” — worked only if the accused bishop felt guilty about what he’d done — or failed to do.

Many did not.

“Getting to be a bishop doesn’t come from a deficiency of ego,” said Michael Merz, an Ohio federal judge and National Review Board chairman in the mid-2000s. “They don’t like being told by anyone what to do.”

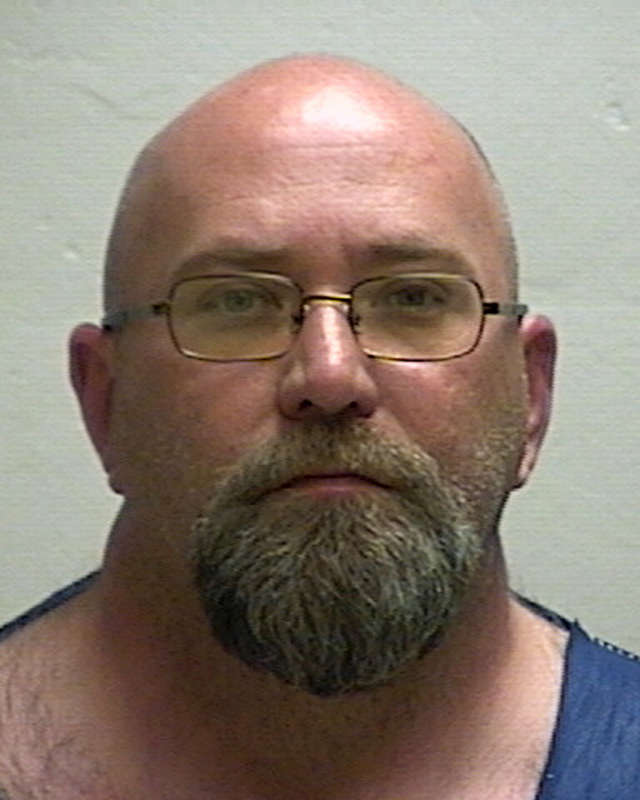

Bishop Robert Finn was firmly in that obdurate camp.

The bishop of Kansas City-St. Joseph, Mo., was unapologetic when he met in 2011 with Jim McConnell, a deacon-in-training at Finn’s residence. The meeting came shortly after news broke that police had arrested a priest in the diocese on child-pornography charges — and that church leaders, including Finn, had known about the Rev. Shawn Ratigan’s photos of naked young girls for months, but had done little about it.

Instead, when Ratigan attempted suicide after the discovery of the photos, Finn sent him to a psychiatrist and then transferred him to a convent where he continued to work around children.

McConnell, who was slated soon to be ordained by Finn, had a question for the bishop: Was it more important to protect the church than to protect children?

“I don’t believe that people can be thrown away no matter what horrible things they’ve done,” Finn said, in a recording obtained by the Inquirer and Globe. “If I had any sense of wanting to hide any incident, I would say it was probably the suicide. … But it wasn’t because I thought that meant that he was guilty. I just think it was just such a sad, shameful thing, that of all people, a priest would try to kill himself.”

McConnell was stunned at Finn’s sense of priorities and his self-pity. Finn called the crisis his “9/11” and talked about wanting to hide in a cave. When McConnell left the meeting, he gave up his dreams of becoming a deacon.

McConnell was just one casualty in Finn’s long battle to stay in power and refusal to admit responsibility. Some parishioners felt Finn had also put their children in harm’s way by concealing his concerns about Ratigan, a priest who had worried a school principal so much that she warned church leaders in May 2010 that he fit the profile of a child predator.

When parishioners asked why Ratigan had been hospitalized and then sent to the convent, the bishop advised church leaders to say little about what happened.

“I tend to want to err on the side of caution and saying less,” Finn wrote in an email obtained by the Inquirer and Globe.

So Elizabeth, a school librarian at St. Patrick’s in Kansas City, had no clue that she should be worried about inviting Ratigan, her parish priest, for dinner soon after his return from psychiatric treatment. No one told her about the photos of young girls found on Ratigan’s laptop or the real reason he was sent away weeks earlier. Speaking publicly for the first time in a recent interview, Elizabeth said Ratigan was distracted that night at dinner, focused on his phone and apparently texting under the table.

Her 9-year-old daughter was also present, wearing a blue skirt. Later, Elizabeth would have to identify it for the FBI when photographs shot up her daughter’s skirt were found among Ratigan’s lewd photos.

“It was sickening,” Elizabeth said. “He used our confessions, our personal time, every ounce of everything he could to get closer to us, and used our weaknesses to keep us blind right up to the end.”

Elizabeth’s full name has been withheld to protect the identity of her daughter. Another victim, Andrea Gnefkow, who was in high school when Ratigan secretly took photos of her sleeping and in a bathing suit, said she felt more violated by the bishop’s failure to intervene.

“Father Shawn is mentally ill, but Bishop Finn is not,” Gnefkow said, speaking out in her first interview. “Bishop Finn just covered it up to save himself – and obviously it didn’t do any good.”

Finn clung to his position for nearly three more years after his own guilty verdict, the trial and conviction of Ratigan, and even in the face of the massive petition campaign and a 2014 public plea for papal intervention from Cardinal Sean O’Malley, archbishop of Boston, in a nationally televised 60 Minutes interview.

Not that Finn was above punishing priests who offended him in other ways. He booted a priest who publicly criticized him, the Rev. Matthew Brumleve, to a parish 30 miles outside of Kansas City. Brumleve had intentionally omitted Finn’s name from prayers he said at each Mass and had invited McConnell, the deacon-in-training who quit in protest, to explain to parishioners at Holy Family that he couldn’t bring himself to kneel in front of the bishop and promise obedience.

These days, Finn, 65, serves as the spiritual leader at a convent surrounded by soybean fields outside Lincoln, Neb.

His pulpit is smaller, but he retains the title bishop emeritus, receives a generous pension, and continues to make public appearances, including at an anniversary Mass earlier this year for the bishop of Lincoln.

Approached by a reporter last month as he was walking his golden Lab on the dirt roads near his home, Finn declined to be interviewed. As he turned on his heels, Finn had one request: “Please respect my privacy and don’t take any photos.”

Finn’s comfortable life after scandal is typical in a church where more than 100 living U.S. bishops have been allowed to quietly slide into retirement and remain unscathed after accusations of abuse or misconduct levied against them.

But not in Wyoming.

There, Bishop Steven Biegler is the driving force behind a reinvigorated investigation that could send one of his predecessors, now 87, to prison.

After arriving in Cheyenne last year, Biegler met with the most Rev. Joseph Hubert Hart, who had led Wyoming’s Catholic Church for nearly a quarter-century.

Hart had remained visible and popular, even in retirement — and despite being implicated in a raft of abuse allegations. In 2002, a year after he stepped down, police investigated a claim that Hart, as a bishop, had repeatedly pressured a 13-year-old altar boy to expose himself, once during confession. Six years later the church paid $10 million to settle claims including those of that accuser and five others who said Hart sexually abused them during his days as a priest in Kansas City, Mo.

In 2009, the Wyoming diocese welcomed another new prelate, Bishop Paul Etienne. Soon after he arrived, Etienne became uncomfortable with the high profile Hart maintained around Cheyenne.

After reading depositions describing Hart’s behavior – including claims he plied victims with liquor and pornography and sexually assaulted boys on weekend trips or in the church rectory – Etienne wrote in 2010 to the Vatican office that investigates bishops and priests.

Nearly two years passed before he was told that Pope Benedict had authorized a preliminary investigation into Hart’s alleged misconduct. Despite his repeated follow-ups, Etienne never heard another word.

“I was less than pleased with the response that I got,” he said in an interview. “I found the process to be inadequate to the seriousness of the need.”

So in 2015, before leaving for a new assignment as archbishop of Anchorage, Alaska, he took one step he could: Etienne barred Hart from public ministry in Cheyenne.

A few months after Biegler stepped in as Etienne’s replacement, he got the results of the Vatican inquiry: It said investigators had deemed the evidence against Hart inconclusive and closed the case in 2015.

Biegler wasn’t convinced. The police investigation of the case, in particular, seemed flawed to him.

So, last year, at a training session for new bishops in Rome, he asked the Vatican to let him reopen and broaden the inquiry. In July, his office announced that its review found the allegations against Hart to be credible. Church officials in Kansas City soon followed suit, saying they too now believe Hart’s accusers almost 30 years after the first of them came forward in 1989.

Among them was Kevin Hunter, who told family members Hart abused him when he was a boy in Kansas City. Hunter suffered with drug and alcohol dependency for years and died in 1989 of AIDS. Three years later, his relatives reported the abuse to the diocese, to no end.

“I was sick to my stomach when he became a bishop and moved to Wyoming,” said Hunter’s sister, Kathy Donegan. “He thought he was so powerful that he was beyond any accountability.”

Hunter’s brother, Darrel Hunter,71, said his family hopes Biegler’s actions signal the church may be on the road to repair.

“I don’t think I’ll see it in my lifetime,” said Hunter. “But I see glimpses of it now.”

In August, Cheyenne police reopened their investigation into Hart and established a hotline to field sexual-abuse complaints. Unlike many states, Wyoming doesn’t have a statute of limitations for sex crimes, which means the retired bishop could be tried for decades-old offenses. At least one new accuser has come forward.

Hart now lives in a gated private community in Cheyenne, his housing, health, and retirement benefits covered by the church. He answered his front door one afternoon in October, an oxygen tank beside him, but declined to talk to a reporter. Through an attorney, he has denied all claims.

Biegler, the current bishop, noted that the path to reopening the investigation there was different than in states such as Pennsylvania, where prosecutors have led the charge.

“Government stepped in [there] because they felt that the church was getting it wrong,” Biegler said in an interview. “Here, we stepped in because we felt the police got it wrong and that had an effect not only here in the diocese” but in Rome.

This past spring, Biegler traveled to New York to visit the man who accused Hart in 2002. The bishop came to personally apologize on behalf of the church.

“I remember thinking, ‘What the f—- am I going to do with an apology?’ ” said the alleged victim, who asked not to be identified. “And then you realize it actually means a lot – to be believed and … to think that this guy is actually going to make something happen.”

This month, U.S. bishops will gather in Baltimore to debate — once again — how to regain the trust of the faithful.

Boston Cardinal Sean O’Malley, the pope’s chief adviser on sex abuse, said in an interview he is eager to see new proposals aimed at holding bishops accountable. He would also like to overhaul past reforms that didn’t work, such as the church audits that gave some dioceses a clean bill of health, which civil authorities later showed to be misleading.

The favorable audits in Pennsylvania and across the country “kind of lulled me into a false sense of security. I mean, how could we have all of these dioceses not being compliant? How could this happen?” said O’Malley, who himself recently came under criticism for not responding to a 2015 letter about McCarrick’s alleged misconduct. “Obviously what we’ve done in the past hasn’t worked.”

To date, the pope has not publicly responded to a reform proposal put forth by the current president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Cardinal Daniel DiNardo — suggestions that include creation of a confidential, third-party system for reporting problem bishops and new restrictions for retired prelates who left their posts in disgrace. Instead, Francis has summoned top bishops worldwide to Rome in February to address the growing crisis.

Francis’ own record on the sex-abuse crisis has been halting and uneven. He earned plaudits early in his papacy by pledging to create a first-of-its-kind Vatican tribunal to adjudicate bishop sex-abuse issues, only to abandon the plan within a year amid strong resistance within his own hierarchy.

And when the pope accepted the resignation of Cardinal Donald Wuerl last month over allegations that he helped cover up abuse decades ago in Pennsylvania, Francis gave abuse victims little comfort. The pontiff praised Wuerl’s “nobility” for agreeing to resign and said that Wuerl would stay on as caretaker of the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C. until a replacement could be found.

Do you find this story valuable? Support journalism at The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Daily News and Philly.com by subscribing.

Many victims and a growing segment of laity believe the time for trusting the hierarchy’s vows to police itself has passed.

In August, founding members of the National Review Board wrote to DiNardo requesting that he appoint them to a new committee to ensure bishop accountability.

The only response? A letter acknowledging that their message had been received.

Based in part on that dismissive response, one founding board member, Washington lawyer Robert S. Bennett, remains unconvinced the nation’s bishops are ready to change.

“This is a church that has been around for 2,000 years,” he said. “I think an awful lot of them believe that eventually this too will blow over.”

Nicole Dungca, Jeremiah Manion, and Todd Wallack of the Globe staff contributed to this report.

Correction: A graphic in an earlier version of this story included a photo of Bishop John Quinn of Minnesota that was misidentified as Bishop A. James Quinn of Cleveland. John Quinn was not part of the committee that drafted the church’s child protection policies in 2002, and has not faced criticism of his record on sexual abuse.

Please click here to read this special report in full: http://www2.philly.com/news/pennsylvania/catholic-church-bishops-sex-abuse-coverup-pennsylvania-west-virginia-wyoming-20181103.html