A year after COVID-19 funding ran out, Pennsylvania childcare providers remain in a staffing crisis

The American Rescue Plan Act helped childcare providers survive through COVID-19. Now, they’re struggling to stay afloat.

After the onset of COVID-19 drove down business for childcare providers, the federal government stepped in to help. Grant funding came through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in 2021 to stabilize the already-fragile sector, helping providers survive the most difficult and straining times.

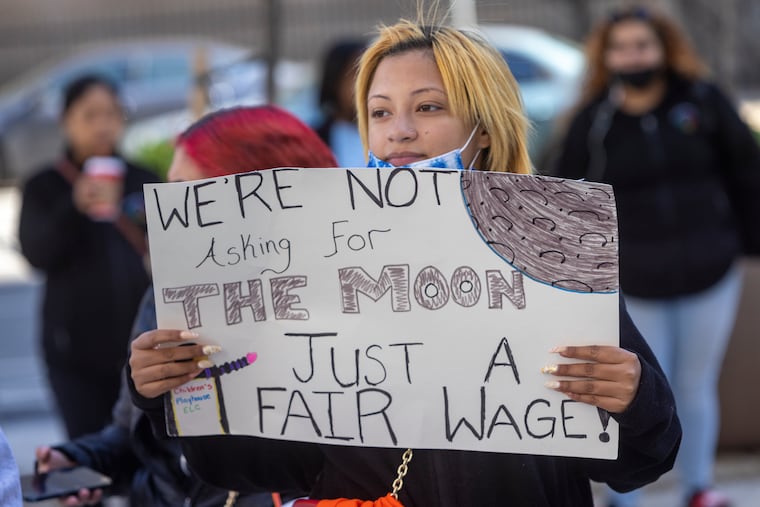

But that funding ran out about a year ago. Now, even as life has normalized since the pandemic, local providers face a staffing crisis and say that they are back again to just treading water, forced to pass higher prices onto families.

» READ MORE: Day-care owners are fighting for survival as federal funding runs out this month

A new report from the Century Foundation (TCF) supports their assertions. TCF, a think tank based in New York, found that in Pennsylvania since 2019, childcare employment has dropped by 40%, and that there has been a net loss of over 600 childcare programs in the state since the pandemic began. For families, childcare costs have increased by 18% since 2019, and the average price to put an infant in day care is currently $14,483 per year.

“It’s hard to get quality teachers. It’s hard to retain staff,” said Kashmire Moore, owner and director of Kaiden’s Korner Childcare Services in East Kensington. She currently has two employees and said she would love to hire more but simply doesn’t have the budget to bring in more staff.

“Which is crazy because we’re the ones who keep things going. Doctors need childcare, police officers need childcare, everyone needs childcare,” she said. “But I feel like we’re kind of like the minion. We don’t get a lot of funding.”

A staffing crisis

With the economy as a leading factor in Donald Trump’s reelection, some might assume childcare’s present struggles are driven by inflation. But according to Julie Kashen, director of women’s economic justice and a senior fellow with TCF who wrote the new report, that is the wrong impulse.

“Historically, childcare prices have risen faster than inflation … in particular right now, it is really related to needing to make up the gap in funding,” she said.

Pennsylvania’s 2025 fiscal year budget includes a $26.2 million increase in childcare funding that would cover some of the ARPA gaps, like lowering co-pays, but advocates say that is nowhere near enough. Strong Start PA, a childcare advocacy coalition, is calling for an additional $284 million in new and recurring state funding to aid the struggling sector.

“Providers are needing to make up this money somehow in order to keep operating. So what we’re seeing is that they’re raising their prices. We saw in Pennsylvania, more than half of providers said they’ve raised their tuition in the past six months,” Kashen said.

On average, there is a $57,000 difference in income for Pennsylvania families with children under 5 in paid childcare and those without childcare, according to TCF’s report.

“We’re growing the income gap between who has and has not,” she said.

Unis Bey, the owner of Grays Ferry Early Learning Academy and a childcare advocate, has lost four staff members over the last year, a reduction of nearly 50%. She said that for her facility to maintain its high marks with the state’s STARS rating system (which measures childcare quality) and receive proportional state funding, her staff members have to meet the system’s educational requirements, since the system incentivizes providers to reach for higher STAR levels. But people with advanced degrees may be able to find better-paying work elsewhere.

In general I think childcare is suffering

“We don’t have the ability to pay what our colleagues in the school districts offer,” she said, explaining that sometimes she can compete by offering attractive benefits packages. Bey’s program is STAR4, the highest rating possible.

“With the ARPA funds, that allowed us to give our teachers bonuses or increases,” she said.

Aaron Simmons, the owner of Teachable Moments Childcare in West Philly, said that he, too, has lost four staff members over the last year. He would like to move from STAR2 to STAR3 but can’t afford to hire the staff it would require to do so.

“It’s just really difficult to pay for that,” he said. “I would have to pay them for two months before I would see any change in how much money I would be receiving from the state.”

But staffing isn’t the only place he feels the loss of funding. He would like to upgrade Teachable Moments’ playground but doesn’t have much money left over for reinvestments or savings. He knows of two other childcare providers nearby that have recently closed because of the lack of funding.

“In general I think childcare is suffering,” he said.

Even though Bey said that the last year has been difficult for her and other childcare-center owners, she has mixed feelings about where the sector is right now. She greatly appreciated the ARPA funding when she had it, but knew that it was designed to be a stabilizing temporary fix during COVID-19, not a permanent solution. Bey hopes that this can be a moment to find a more sustainable way forward.

“We received all of these dollars from ARPA, but programs still closed their doors,” she said. “We have to figure out why [that] happened.”