Chemicals that tainted Bucks, Montco drinking water found in lettuce, beef, even chocolate cake

The Food and Drug Administration found PFAS chemicals in produce, dairy, and meat products.

Ground turkey, chocolate cake, kale — laced with a serving of toxic chemicals.

People across the country, including in Bucks and Montgomery Counties, are already grappling with the effects of drinking potentially harmful chemicals known as PFAS. Newly revealed research by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration shows Americans are eating the substances, too.

Tests of produce, meat, and dairy from areas near known sites of PFAS contamination showed high levels of the compounds, which were used for decades in nonstick or stain-resistant products like Teflon and Scotchgard, and in industrial wares including firefighting foam.

>>Read more: Setting clean water standards is the EPA’s job. Pa. and other states are doing it instead.

The FDA said in its report that the contaminated food samples “are not likely to be a health concern,” but advocates and experts on Thursday said the tests were another cause for concern in a crisis they say federal regulators have not properly addressed.

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl chemicals, are associated with cancers, thyroid disease, immune system problems, decreased fertility, and lower birth weight. Addressing contamination in drinking water, groundwater, air, and soil has become an urgent cause for many officials across the country and for a bipartisan group in Congress.

The FDA tested produce bought at farmers’ markets near a PFAS production plant and other food purchased in the eastern United States, as well as dairy products from a farm near an Air Force base in New Mexico. Many of the items contained levels of PFAS well above the Environmental Protection Agency’s current health advisory level for consumption in drinking water. There are currently no enforceable environmental or health standards for PFAS in the U.S.

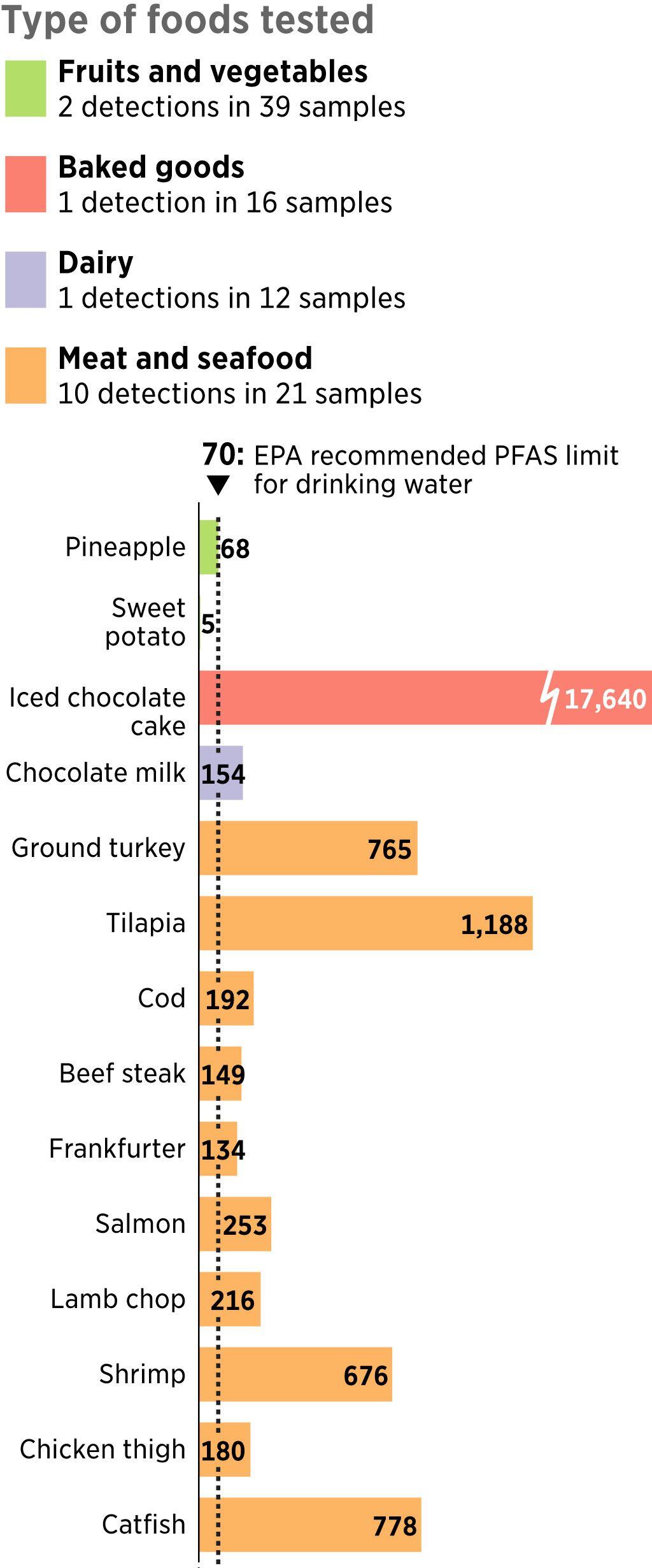

PFAS in Food

The FDA sampled produce, meat, dairy and grain products in multiple cities in Maryland, Delaware, West Virginia, Virginia, Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky. PFAS was not detected in 89 percent of samples, but high levels of some types of PFAS were found in other food items. There is no federal regulation for PFAS in food or water. The Environmental Protection Agency's current health advisory for drinking water recommends not drinking water that has 70 ppt or more of PFAS, although scientists have said the water advisory can’t be directly applied to food. Some federal research has suggested PFAS poses health risks in smaller amounts.

70: EPA recommended PFAS limit for drinking water

68

Pineapple

5

Sweet potato

17,640

Iced chocolate cake

154

Chocolate milk

765

Ground turkey

1,188

Tilapia

192

Cod

Type of foods tested

149

Beef steak

Fruits and vegetables

134

Frankfurter

2 detections in 39 samples

Baked goods

253

Salmon

1 detection in 16 samples

216

Lamb chop

Dairy

1 detections in 12 samples

676

Shrimp

Meat and seafood

180

10 detections in 21 samples

Chicken thigh

778

Catfish

Type of foods tested

Fruits and vegetables

2 detections in 39 samples

Baked goods

1 detection in 16 samples

Dairy

1 detections in 12 samples

Meat and seafood

10 detections in 21 samples

70:

EPA recommended PFAS limit

for drinking water

Pineapple

68

Sweet

potato

5

Iced chocolate

cake

17,640

Chocolate milk

154

Ground turkey

765

Tilapia

1,188

Cod

192

Beef steak

149

Frankfurter

134

Salmon

253

Lamb chop

216

Shrimp

676

Chicken thigh

180

Catfish

778

The FDA says it is now working on testing foods for PFAS and reviewing current uses of PFAS in food packaging and cookware, such as grease-proof paper and pizza boxes.

But experts pointed out that effects of some of the types of PFAS found in the products have been little studied. They called Thursday for the EPA to require testing of sewage sludge, which is commonly used as fertilizer and has been found to transfer PFAS to crops.

“This really is another blow to those who live in contaminated areas, who are already experiencing negative economic impacts and fears of elevated health risks,” said East Carolina University researcher Jamie DeWitt.

The EPA’s drinking-water advisory level can’t necessarily be used as a benchmark for PFAS in food, DeWitt said, because it is based on the amount of water someone consumes in a lifetime — and people consume more water than chocolate cake or lettuce. Still, the chemical concentrations in the food are “quite high,” she said, and could disproportionately affect communities near PFAS sources.

“You’re going to be going to that farmers’ market for your produce on a weekly basis, so your exposure is going to be quite high,” said Tom Neltner, chemicals policy director at the Environmental Defense Fund.

The FDA presented its research at a conference in Finland last week. The Environmental Defense Fund and Environmental Working Group obtained a copy of the FDA’s presentation, which EWG provided to The Inquirer. The testing was first reported by the Associated Press. An FDA spokesperson referred The Inquirer to the agency’s website in response to a request for comment Thursday.

Manufacturers phased out PFOA and PFOS in the early 2000s, though they are used in some imported products.

Federal scientists have said even amounts of PFAS that would be considered safe under the EPA’s current advisory could pose health risks. Simultaneous efforts are underway in various states, including Pennsylvania, by the EPA to determine what amount of PFAS is actually safe for drinking water. The EPA has said it will be several years before it establishes a drinking-water standard.

High levels of PFOS, one type of PFAS that was widely discovered in drinking water, were found in samples of ground turkey, salmon, steak, and chicken thigh, among other meats. Store-bought chocolate cake and chocolate milk also had high chemical levels, as did a variety of leafy greens grown within 10 miles of a PFAS production plant.

PFAS can get into produce through sewage sludge, contaminated irrigation water, or contaminated soil, said EWG’s Colin O’Neil. And it could be easy for the contamination to spread beyond PFAS-ridden areas: Some states buy sewage sludge from other states.

FDA tests of dairy products showed that when cows consumed PFAS-laced water, they made PFAS-laced milk. In New Mexico and Maine, two widely reported stories of dairy farmers shutting down their farms because of PFAS contamination have raised alarm. In March, Maine became the first state to require all sludge to be tested for PFAS.

“It’s really, at this point, time to take action to restrict people’s exposure so their risk can be reduced,” DeWitt said.