Threatening veto of spending bill, White House opposes two PFAS cleanup measures

The Trump administration objected to PFAS-related items in the House defense spending bill, along with a list of other disagreements, including over provisions that would impede Trump’s efforts to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Threatening to veto the House’s defense spending bill, the Trump administration says it does not want Congress to authorize the military to clean up agricultural water sources contaminated with PFAS, and objected to a plan for the military to phase out its use of firefighting foam containing the harmful chemicals.

The administration voiced its objections to two PFAS-related items attached to the bill in a statement Tuesday that also listed dozens of other concerns, including provisions that would impede President Donald Trump’s efforts to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. The $733 billion bill also does not contain enough funding, the administration said.

The House was expected to begin debating amendments to the spending bill late Wednesday, but votes will likely come later in the week. It includes a package of amendments addressing contamination caused by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. The Senate last week passed a PFAS package in its own bill.

Environmental activists had praised the efforts, which include provisions to add PFAS to the national water quality monitoring network, require drinking water utilities to test for PFAS, and require that PFAS waste be incinerated. Tens of thousands of residents near former military bases in Bucks and Montgomery Counties were among the first in the country to discover PFAS contamination in their drinking water and have been pushing for federal action on the issue.

The White House objected to the provisions in the bill in part because it said the cleanup cost would be too high and the agriculture-related measure “singles out” the Department of Defense. Most nonmilitary sources of PFAS pollution in the U.S. are private manufacturers.

“With this veto threat, President Trump has said he would hold up funding for our troops because his administration does not want to act swiftly to eliminate toxic PFAS chemicals to protect service members and the communities that support them,” Rep. Madeleine Dean (D., Pa.) and Rep. Dan Kildee (D., Mich.) said in a statement Wednesday.

The widespread use of PFAS by the military, primarily in firefighting foam, and by manufacturing companies has led to a contamination crisis in communities nationwide. The chemicals threaten human health and have recently been found not only in drinking water but in agricultural fertilizer, cows’ milk, and produce.

Maine has required testing for PFAS in sludge commonly used as fertilizer; dairies in New Mexico and Maine have closed; and after the chemicals were detected in Massachusetts cranberry bogs, the juice maker Ocean Spray would not accept the crop and the berries were incinerated.

Recent Food and Drug Administration tests of produce showed elevated levels of contamination in fruit and vegetables grown near contaminated sites. The FDA said they did not pose health risks. PFAS has also been found in fish and shellfish; in New Jersey areas with PFAS contamination, residents were advised to eat only very limited amounts of fish they caught.

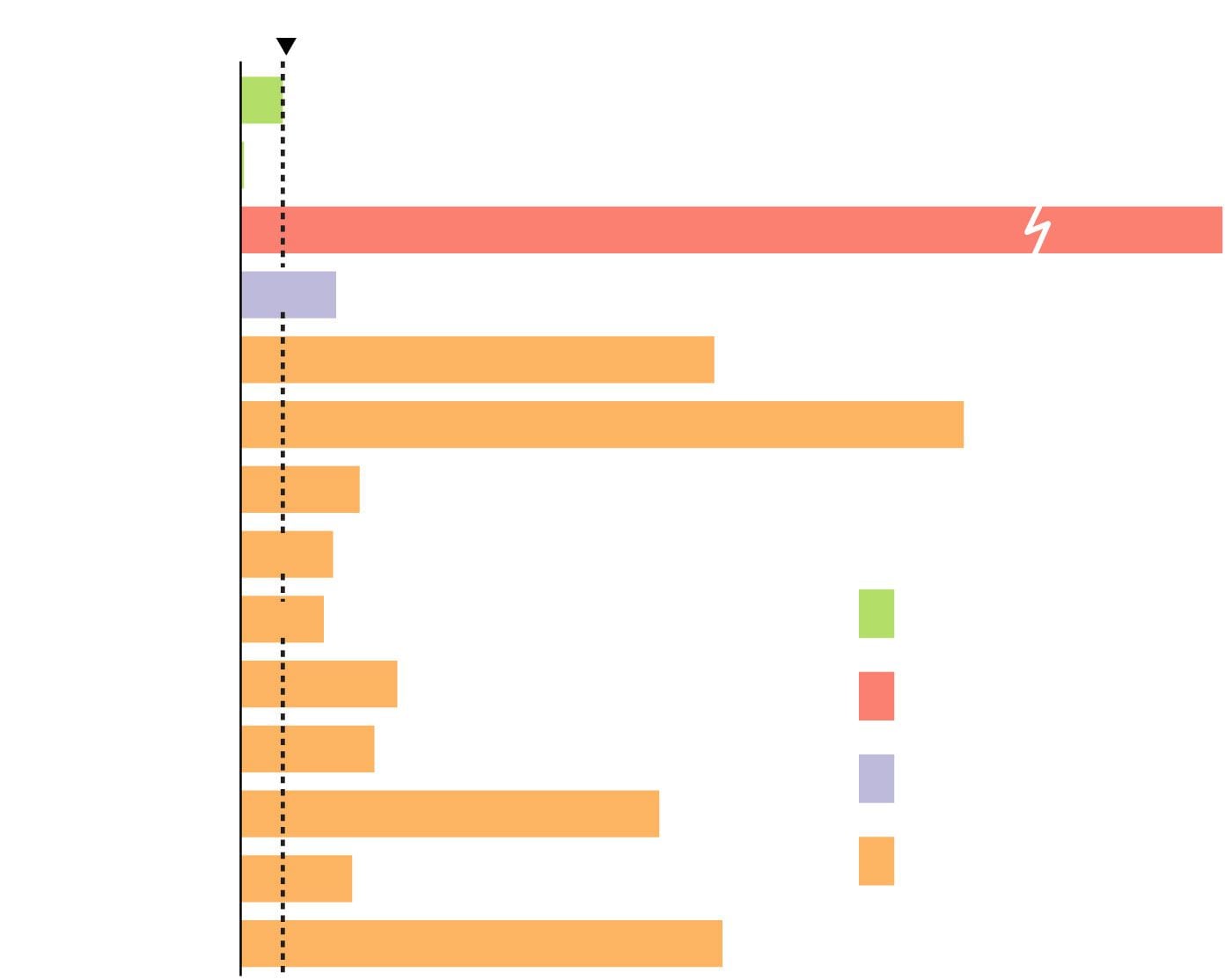

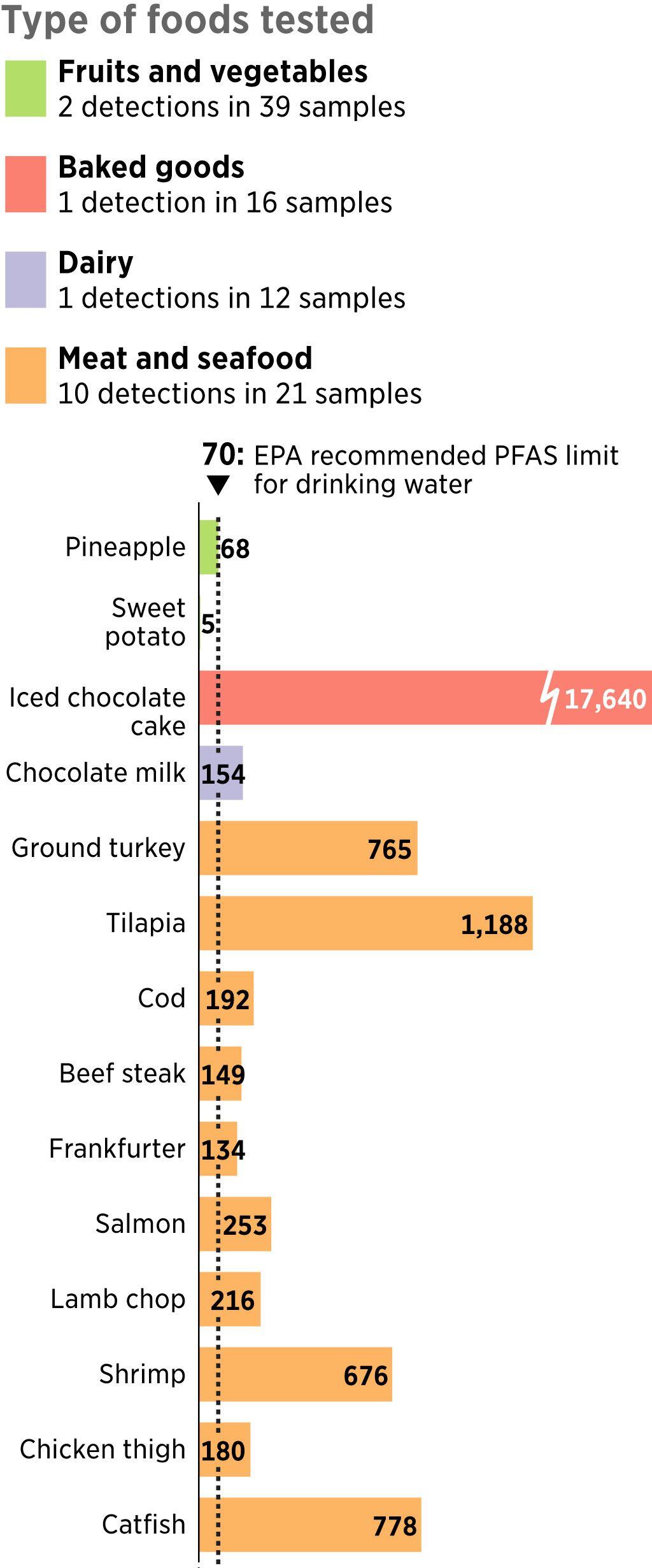

PFAS in Food

The FDA sampled produce, meat, dairy and grain products in multiple cities in Maryland, Delaware, West Virginia, Virginia, Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky. PFAS was not detected in 89 percent of samples, but high levels of some types of PFAS were found in other food items. There is no federal regulation for PFAS in food or water. The Environmental Protection Agency's current health advisory for drinking water recommends not drinking water that has 70 ppt or more of PFAS, although scientists have said the water advisory can’t be directly applied to food. Some federal research has suggested PFAS poses health risks in smaller amounts.

70: EPA recommended PFAS limit for drinking water

68

Pineapple

5

Sweet potato

17,640

Iced chocolate cake

154

Chocolate milk

765

Ground turkey

1,188

Tilapia

192

Cod

Type of foods tested

149

Beef steak

Fruits and vegetables

134

Frankfurter

2 detections in 39 samples

Baked goods

253

Salmon

1 detection in 16 samples

216

Lamb chop

Dairy

1 detections in 12 samples

676

Shrimp

Meat and seafood

180

10 detections in 21 samples

Chicken thigh

778

Catfish

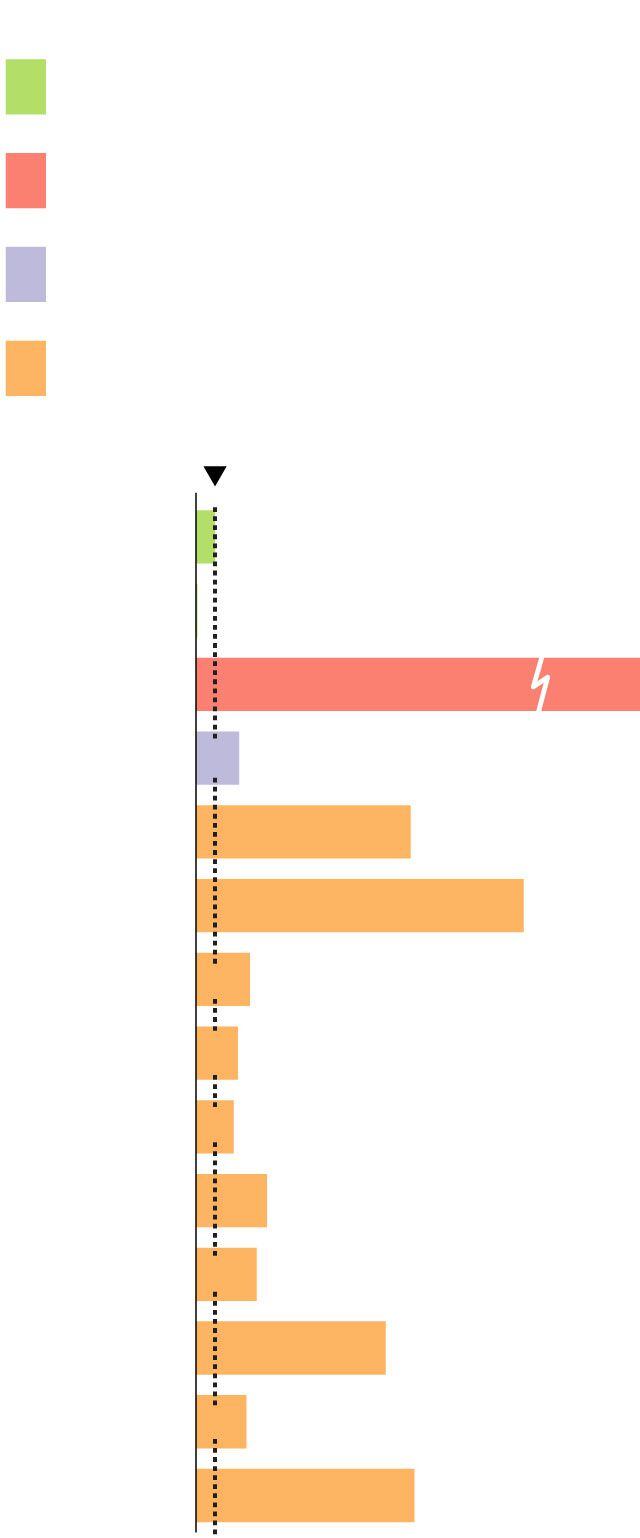

Type of foods tested

Fruits and vegetables

2 detections in 39 samples

Baked goods

1 detection in 16 samples

Dairy

1 detections in 12 samples

Meat and seafood

10 detections in 21 samples

70:

EPA recommended PFAS limit

for drinking water

Pineapple

68

Sweet

potato

5

Iced chocolate

cake

17,640

Chocolate milk

154

Ground turkey

765

Tilapia

1,188

Cod

192

Beef steak

149

Frankfurter

134

Salmon

253

Lamb chop

216

Shrimp

676

Chicken thigh

180

Catfish

778

But as states already mired in problems with drinking water contamination try to address farming issues, the Trump administration questioned whether treating agricultural water should be the military’s responsibility.

The White House said the proposed agricultural cleanup could not be done because there is no federal standard for testing for PFAS in water used for farming. The proposed legislation uses the Environmental Protection Agency’s drinking-water advisory, the only current federal guidance on PFAS consumption, to identify agricultural areas needing cleanup.

Activists have called for the EPA to create separate agricultural standards for PFAS, such as regulations for fertilizer. The EPA in February unveiled a plan to address the chemicals but it will take years to have an effect.

The administration also opposed an amendment that would require the Department of Defense to phase out the use of firefighting foam containing PFAS by 2025, saying the military could not have a viable alternative by then. PFAS-laced foam is particularly effective at extinguishing petroleum-based fires.

Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick, a Republican representing Bucks County, said he was “deeply concerned” by the White House’s opposition to the phaseout deadline.

“Just this week, the president stated that clean water is a ‘top priority’ of his administration,” Fitzpatrick said in a statement. "I remain committed to the establishment of a deadline to phase out the use of fluorinated firefighting foam.”

Dean and Kildee offered an amendment Tuesday that would require the military to phase out PFAS firefighting foam by 2029 instead of 2025.

Staff writer Jonathan Tamari contributed to this article.