Labeled a murderer for 24 years, Philadelphia man is exonerated

It took almost 25 years, but the Philadelphia’s District Attorney’s Office finally conceded that Johnny Berry, who was just 16 years old when he was arrested, did not participate in the murder of Leonard Jones, 73, in the city’s Parkside neighborhood.

It took almost 25 years, but the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office finally conceded that Johnny Berry, who was just 16 when he was arrested in 1994, did not participate in the murder of Leonard Jones, 73, in the city’s Parkside neighborhood.

At the initial trial, the DA offered Berry’s co-defendant, Tauheed Lloyd, a deal to testify against Berry. As a result, Lloyd got a 15½- to 37-year sentence, and Berry got life. And in 2008, when Berry received a hearing on his post-conviction appeals, the DA warned Lloyd that recanting could lead to perjury charges or even a new prosecution for murder.

But Monday morning, at the Stout Center for Criminal Justice, Common Pleas Court Judge Barbara McDermott threw out Berry’s conviction. And the DA — whose Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) has been reviewing the case for the last year — declined to retry him.

“Had the commonwealth allowed Mr. Lloyd to testify without the threat of perjury charges, it’s our belief that Mr. Berry would have prevailed at his [2008] evidentiary hearing,” Assistant District Attorney Tom Gaeta said.

Berry, who served more than 23 years in prison and the past year on parole, said he wished justice had arrived more quickly. But, in the space of Monday’s brief hearing, he saw his future transformed.

“Now, hopefully people won’t identify me as being connected to a murder, and see me as I am — not a criminal,” said Berry, now 41.

Berry was released from prison because he was a juvenile lifer, a class of individuals whose life sentences, imposed when they were under 18, were found unconstitutional under a U.S. Supreme Court decision that emphasized the diminished culpability associated with youth. McDermott, charged with handling his resentencing, had asked the CIU to review Berry’s innocence claim.

There were ample questions about the case, a 1994 gunpoint robbery in which two young men approached Jones and a woman as they were sitting in Jones’ parked van. One held the passenger-side door closed while the other confronted Jones in the driver’s seat and ended up shooting him. The woman survived, but proved an unreliable witness — at times naming Berry as the gunman, other times pointing to him as an accomplice, and still other times saying he wasn’t there at all. In the end, Berry was convicted primarily on testimony by Lloyd, who later admitted that he was motivated by revenge because he believed Berry was a snitch.

Lloyd first came forward in 2002 — motivated, he said, not out of forgiveness for Berry but by a growing understanding of the suffering Berry’s family must be experiencing. But prosecutors were skeptical of his changing testimony.

Berry’s is the seventh conviction the CIU has helped to reverse, according to Patricia Cummings, who heads the unit.

“An important part of this is a willingness to look and try to seek out the truth after a conviction occurred,” Cummings said. “What the CIU is trying to do is go into this probably with a more open mind, a more holistic view, and say you can make determinations regarding credibility, even if someone said 'A' once and they say 'B' now. You have to look at the case in its totality.”

The case never sat right with Shirley Jones Hopkins, Leonard Jones’ oldest daughter. As an investigator with 20 years’ experience, she said, she could see that the testimony, the evidence, just didn’t add up. But her mother and six siblings all wanted justice.

“It was seven against one,” she said. "You’re not going to go against seven young people.”

Even as recently as last year, at Berry’s resentencing, Jones Hopkins joined her family members in asking McDermott to give him at least 35 years to life in prison. “Mr. Berry has never apologized for his actions, nor has he ever taken responsibility," she had said.

On Monday morning, though, Hopkins drove up from Baltimore one more time, determined to finally speak up for what she believed was right. She even brought her 10-year-old granddaughter, to teach her about standing up for her principles.

“I am at total odds with my family regarding this,” she told the court. “But I believe there is ample evidence to support Mr. Berry’s innocence.”

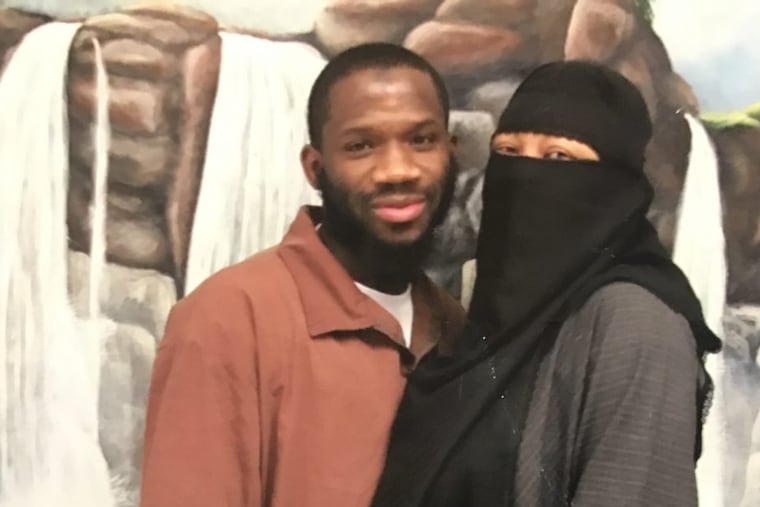

Berry said he’s ready to move forward. He seems to have easily adapted to life on the outside, peaceably living with his wife of 10 years, Qiana, who fought for his exoneration for the past few decades, contacting lawyers, and pushing for his story to be told.

“It’s just a sigh of relief,” she said. “Free! Don’t have to call nobody to say ‘I’m going to Jersey to the mall.’”

He landed a job with a cleaning company and quickly rose to become a supervisor. His first year as an adult in society, and he’s already experiencing the weight of responsibility. Among the simple pleasures is driving again. (He said he’s better at it now than when he was 16, though Qiana’s raised eyebrow indicated otherwise.)

Now, though, he hopes new opportunities will be open to him — without the stigma of a felony on his record.

“I love meeting people and they have no idea I spent 24 years on the inside,” he said.

To celebrate, he said, he planned to take his family down the Shore for a day or two, at last without having to ask a parole officer for permission to travel.