Can good design protect us from the coronavirus? Philly designers pivoting to public health think so.

It’s the first wave of a long-term shift in design: reducing touch points, introducing furnishings that will both encourage and allow for social distancing, and requiring one-way traffic through hallways.

As the coronavirus spread through Philadelphia, the staff at the Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission, the city’s largest men’s shelter, braced as if for a hurricane. To shelter those inside, they hunkered down, encouraging residents not to go outside during the day, turning away new arrivals, and barring nonresidents from a daily meal service that hundreds had previously relied on.

But Jeremy Montgomery, the shelter’s executive director, knew that was unsustainable given the growing and unmet need.

As Philadelphia reopens, he said, “We expect to get flooded with new people requiring shelter because they’ve been couch surfing or other creative solutions, and they really do need that shelter.” So he turned to a new rapid-response effort by the nonprofit Community Design Collaborative, recognizing that reopening during the coronavirus pandemic is not only a public-health problem, but also fundamentally a design problem.

The volunteer effort, which mustered a corps of architects and designers to create a concept in just a week, is rooted in the idea that many simple and low-cost design choices can significantly impact how people interact not only with a space but also with each other. Signage and distance markers can remind visitors to stay at least six feet apart. Way-finding systems can direct the flow of traffic to prevent crowding or collisions. Flexible furniture can allow people to sit farther apart from strangers, or together with family. Soothing colors and welcoming artwork can create a sense of calm in an unsettled moment.

The Community Design Collaborative, run by the Philadelphia chapter of the American Institute of Architects, normally takes on projects that are months in the making, like a whimsical makeover of an aging South Philadelphia Catholic school, a new public park at the edge of Elfreth’s Alley, and an initiative to bring life into underutilized sacred spaces across the city.

But during the pandemic, the collaborative’s director of design services, Heidi Segall Levy said, “We felt we needed to do something more immediate, to provide immediate assistance to the nonprofits we work with that are on the front lines.” So, they created Design A.I.D., short for Design Assistance in Demand.

» READ MORE: New Jersey adds 1,854 probable coronavirus deaths to total after review, sees uptick in transmission

She sees the interventions — informed by CDC guidelines, as well as emerging best practices in the industry — as the first wave of a long-term shift in design, reducing touch points like elevator buttons and door handles, introducing signage and furnishings that will both encourage and allow for social distancing, requiring one-way traffic through hallways.

“It’s really important to think about how much impact the built environment has on behavior and emotional and physical well-being,” she said. “Not just keeping the guests six feet apart, but also how do we reduce the anxiety levels?”

That was critical at the Sunday Breakfast Rescue Mission, a shelter just north of Chinatown that saw dozens of COVID-19 cases in May despite precautions like reducing capacity, spacing out beds, and creating a quarantine unit in a multipurpose room. Eventually, the entire shelter was put under a 14-day quarantine before getting cases under control. Now, Montgomery is looking to a return to something like normal.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia set to be first U.S. city to protect workers against retaliation for calling out coronavirus conditions

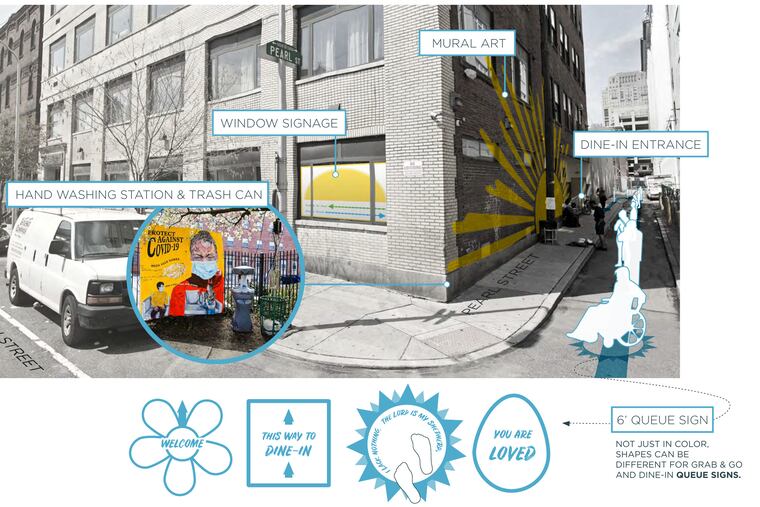

After a virtual walk-through, conducted via Zoom videoconference, a group of 10 volunteer designers came up with a plan to transform the dining room into an inviting space and create clear, color-coded signage directing those not staying in the shelter to a separate, outdoor, grab-and-go meal service. They suggested installing spacers to mark six-foot intervals, hanging artwork of familiar Philadelphia sights to make visitors feel welcome, and bringing in Mural Arts Philadelphia to add a festive mural along the Pearl Street alleyway where guests wait in line for meals.

“We have been able to implement and execute a lot of their ideas,” Montgomery said. “Day to day we don’t have time to stop and think about ... what color our walls should be painted. I think about, how should I care for someone? But we know the physical environment goes a long way in how we care for people.”

Building on that pilot, the collaborative assembled another Design A.I.D. group to work with Berean Baptist Church in North Philadelphia, which will have to juggle social services, support-group meetings, religious services, and more as congregants and organizations return.

A third round of work supported the Nationalities Service Center (NSC) in Center City, where administrators were puzzling through how they could begin restoring language classes, a clothing closet, food pantry, and numerous other services for immigrants and refugees. On a recent afternoon, after a whirlwind week of planning, the volunteer group presented their ideas for both welcoming clients back into the space and communicating messages about how to navigate the space to visitors who may know little English.

The suggestions were comprehensive, from the sneeze guard on the reception desk to six-foot bubbles marked on the floor to the replacement of keypads with contactless access cards to enter secure spaces. The designers created a plan for one-way traffic, moving counterclockwise through the space, with colors, shapes, or origami-inspired decals to mark each destination. They recommended hands-free bathroom fixtures, including a mop sink that could serve as a foot-washing station for Muslim clients to use before praying.

The theme, said Katherine Antarikso, an architect with the firm HOK, was “a sense of welcome.” But the designers also sought to address logistical issues that suddenly loomed important, suggesting offices be reorganized into “neighborhoods” of more public, less public, and private spaces, with diminishing risk of social contacts.

» FAQ: Your coronavirus questions, answered.

The presentation, with its dozens of suggestions, was almost more than the NSC staff could take in all at once. Margaret O’Sullivan, the nonprofit’s executive director, told the designers she was not sure where to start with implementation. The organization, which is returning to work slowly over the summer but will not restore full operations in 2020, was in triage mode, trying to decide which changes were urgent and which could wait. Cost, she said, is a key consideration — especially since the Design A.I.D. architects had advised her that the safest choice to replace the center’s failing HVAC system would require a half-million-dollar upgrade.

But, she told the designers, “It’s very inspirational. It does help you think about, in the midst of such a tragic time, things could get so much better in the building because of it.”