New report shows tens of thousands of Philadelphians are living with hepatitis B and C, as the city pledges to eliminate new cases by 2030

About 25,000 people in Philadelphia were living with chronic hepatitis B and about 53,000 with chronic hepatitis C in 2021.

In a new report on hepatitis B and C cases in Philadelphia, health officials say that tens of thousands of residents are living with the liver infections — and the city has pledged to eliminate new cases by 2030.

About 25,000 people in Philadelphia were living with chronic hepatitis B in 2021, the last year for which data is available. Another 53,000 people had chronic hepatitis C, according to the report, which was released in late May and is the city’s first comprehensive report on hepatitis B and C infections. The city reported 164 hepatitis B and C deaths in 2021.

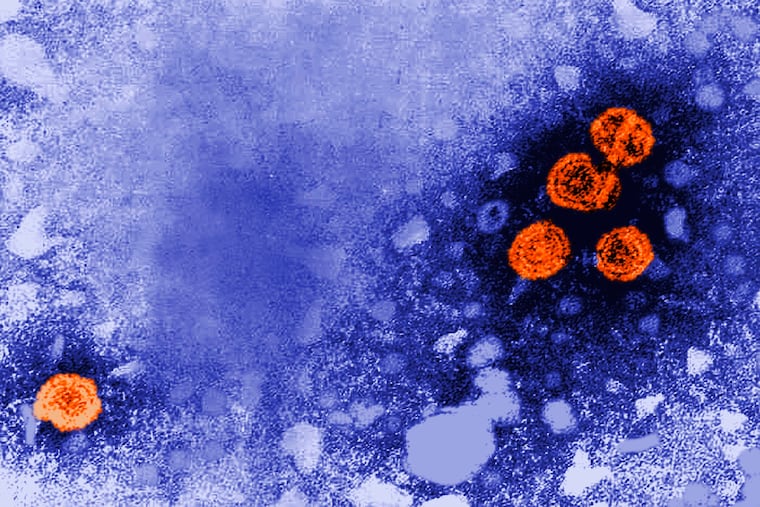

Hepatitis B and C are viral infections spread through blood and other bodily fluids that cause liver damage and cancer if untreated. Hepatitis C can be cured and hepatitis B is treatable, but chronic cases lasting longer than six months are common because people often don’t experience symptoms until the disease advances.

For the same reason, the true prevalence of hepatitis in Philadelphia is likely more extensive than data show. According to the city’s report, the number of new diagnoses of chronic hepatitis has declined slightly over the last several years, said Dancia Kuncio, the viral hepatitis program manager for the health department.

The city recorded 140 new cases of hepatitis C and 13 new cases of hepatitis B in 2021.

“However, these are chronic diseases. So the prevalence [of people living with hepatitis] continues to increase over time,” she said.

It’s crucial, she said, for the city to identify as many cases as they can in order to get patients care that can prolong their lives.

Patients with an acute hepatitis B infection — contracted less than six months ago — can recover to a point they won’t be able to spread the virus, though it will remain in an inactive state in their liver.

Racial disparities in hepatitis cases

The new report highlights significant racial disparities among hepatitis cases in Philadelphia:

In 2021, 61% of new chronic hepatitis B cases occurred among Asian and Black communities.

Most acute hepatitis C cases reported in 2021 occurred among Black and Hispanic patients.

Most chronic cases were reported among Black patients, men, and people between 25 and 44 years old.

There are a number of factors driving hepatitis infections, Kuncio said. Hepatitis can spread through unprotected sex, and can be passed to an infant during childbirth. Most infants in the United States are vaccinated for hepatitis B, and there is also a vaccine available for adults. But these vaccines are less common in other parts of the world, leaving some immigrants vulnerable.

There is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

“A primary driver of hepatitis B in the city is related to people being born in countries where it’s endemic, where it’s passed through childbirth,” including some countries in Subsaharan Africa and Southeast Asia,” Kuncio said. “Some people have had it since they were born.”

She said the city is working with groups who serve those communities to increase access to diagnosis, care and prevention of hepatitis.

“We’re really trying to bring as much education as we can and promote cultural competency and language access amongst providers to ensure that it’s not just certain groups that can receive care for hepatitis B and C,” she said.

The rise of injection drug use in the city has also fueled an increase in hepatitis infections, Kuncio said.

“We’re seeing a lot of folks have these infectious diseases that are consequences of substance use disorder, as the rates of opioid use have increased in Philadelphia,” she said. Health officials say it’s crucial for people who inject drugs to avoid sharing syringes and to use sterile needles to prevent contracting the disease.

‘People need to get in the door’

The city has pledged to eliminate new cases of hepatitis B and C by 2030, and expects this year to release their plan for curbing both diseases.

Kuncio says she’s optimistic about the effort, but acknowledged it will require extensive community outreach — especially for patients who already face barriers to getting care.

“You can have a testing recommendation all you want, but people need to get in the door and be willing to be tested,” she said. “We need to be looking at how people access care, and think about what is preventing them from receiving information.”